|

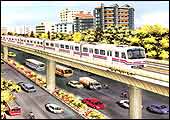

| Bangalore's elevated light rail transit system

is mired in red tape |

Transportation

experts will tell you that a city needs a mass transit system when

its population crossed 1 million. By those standards, 35 Indian

cities are eligible. Yet, only Kolkata has a small metro system.

Chennai's new system-running at only a sixth of capacity because

buses serve the same route better and more cheaply-runs over exactly

8.55 km. And only 16 km of Delhi's under-progress mass transit system

will be running by 2003.

But Bangalore's Elevated Rail Transit System

must surely win some sort of an award for sloth.

The need for a mass transit system was projected

as early as 1988, when a World Bank study said that the rate at

which the population was growing and the traffic density was increasing,

made it imperative for Bangalore to have a mass rapid transit system.

The population of Bangalore then was 3.4 million.

Today, its 7.2 million people are served by a grossly inadequate

fleet of 1,800 buses and 60,000-strong fleet of smoke-belching autorickshaws.

No wonder, then, that Bangalore has the largest personal transport

fleet-more than 9 lakh two-wheelers-in the country after Delhi.

It took the Karnataka government five years

to set-up a committee to examine whether a mass transit system was

needed. Finally in 1993, the Karnataka government decided to build

an elevated light rail transit system (ELRTS): a 99-km system of

air-conditioned light coaches borne on viaducts on arterial roads.

It made sense. Elevated tracks cost Rs 100 crore per km compared

to Rs 300 crore per km of underground railway. Surface tracks are

cheaper by 25 per cent, but where's the space? ELRTS' total cost,

estimated at Rs 4,000 crore in 1994, has ballooned to Rs 10,000

crore. The government-owned Bangalore Mass Rapid Transit System

Ltd was set up in 1994. Since 1995, a cess was levied in Karnataka

to garner funds, but only Rs 290 crore has been collected over six

years.

|

| Chennai's 8.55 km-long mass transit system is

struggling |

Its not just about money, it's about planning

and common sense. Chennai's fledgling mass transit system runs at

a sixth of capacity, a ridiculous statistic in a country where buses

and trains are always full. That's because buses cover more ground

and do it more cheaply than the limited mass transit system in Chennai.

The people who built the system, the Indian Railways, didn't think

it worth their while to sort out the details with the officials

who run the city. Instead of complementing the bus system, the mass

transit system competes with it. And since the Railways have invested

a lot of money in the system, there's no likelihood of fares-costly

to those used to the cheaper buses-coming down. There are no hope

of profits in Chennai.

In Bangalore, it was clear from the start that

a private partner was needed. Nearly all mass transit systems run

at a loss worldwide. In 1996, the UB Group won a global bid. Since

then, it's been a litany of delays and disputes. The government

and the UB group are presently re-negotiating financial terms. If

all goes well, the first trains might start running by 2007 over

the first phase of 21 km. As for the second phase of 64 km, no one's

even talking about it.

-Venkatesha Babu & Nitya

Varadarajan

Commuter Diaries: Days In

The Life Of The Traveller

|

Delhi: Battling For Survival On The Road,

Reading Hope In The Signs

It was my first week in Delhi, and

I was on my way to office in Connaught Place. It was 9 a.m., and

I had to be in before 10, or else join the sack race. I rose at

7 a.m. and was in the bus by 9:10. Middle-income office-goers clerks,

secretaries, travel agents joined me on the chartered bus. Almost

immediately, the overworked speakers pounded out the latest in Punjabi

pop as the conductor pounded on the side of the bus to clear the

way ahead. After a week of back-crunching stops and abuses, I had

enough. I know there's a ring railway somewhere, but where? The

next day, I get on my motorcycle, like 22 lakh others. We weave

through the buses and some of the 9 lakh cars. The air is surprisingly

clean, thanks to the CNG the buses and autos now imbibe. But driving

is getting harder. About 10,000 new vehicles join the daily battle

every month, ensuring the once open six-lane roads are medieval

jousting grounds.

But every day, I see more men in those yellow

hard hats. I see the hope in the signs they place on excavated streets,

pavements and parks-they read, Delhi Metro.

-Moinak Mitra

Mumbai:

Surviving Crush Hour And Dreaming Of The West Island Freeway. Mumbai:

Surviving Crush Hour And Dreaming Of The West Island Freeway.

The blast of the air horn of the 7:59

Churchgate local jars me awake from my standing snooze. I clutch

the well-worn iron grip tightly as the train's motors whine their

way out of Borivali station. Office goers fling themselves aboard

desperately. The next train is five minutes away. But in the mad,

frantic rush of the Mumbai commute, these few minutes could mean

missing the next of a series of links that makes up an average Mumbaikar's

daily grind: The bus from the station, the share-taxi, the car pool,

the lift on the collegue's bike-every step is charted with split-second

precision. This is a first-class compartment, but I'm squashed in

between veterans who've buried their head in papers neatly folded

to book-size. I'm one of the five million who spend an average of

two hours on the trains. On the roads, 55,000 smoke-belching taxis

are stuck in ever-increasing, jams. The humid air is acrid and insufferable.

The trains are jammed to four times their capacity, but there's

no choice. Yes, I've heard of the West Island Freeway, the roadway

that will soar over the western seaboard, and deposit us downtown.

We've all heard of it-for the last 20 years.

-Abir Pal

Bangalore:

Living My Life Without Fourth Gear Bangalore:

Living My Life Without Fourth Gear

My car has a fifth gear, but I've never

used it in Bangalore. Actually, I've rarely got beyond third. Driving

a car in Bangalore means competing against the streams of two-wheelers-just

one of 9 lakh-that clog the once-empty roads. As I grow older I

don't fancy myself doing the weave-of-death astride a scooter or

motorcycle. So I drive, slowly, breathing in the foul exhaust of

the thousands of vehicles forced on our roads because we have no

transport system worth the name. I see school children hanging to

life on the footboards of the 1,800 rickety buses, or packed in

like sardines in a cycle-rickshaw with a precarious, rusting iron

cage on its back. I see the hard-working folk stuck in buses for

an hour for a 14-km commute. Of course, we do have flyovers now-exactly

two of them. To top it all, I pay more for my petrol than anywhere

else in India: I'm contributing my bit to fund the Bangalore light

rail elevated system. I've been doing it for six years now, and

I'm told I might see the first train by 2007. Which means they might

start construction by then. Hurrah! At least my children will be

able to use the fifth gear.

Venkatesha Babu

Suburbia's Sprawl And The

New Outlying Culture

|

| Salt Lake City, Kolkata: absorbing the swamp

of grandma Kolkata |

Like everywhere,

Indian suburbia strives to better the decaying city, creating its

own nuances. ''The suburb has not really thought of itself as outside

the city,'' says Dr Radhika Chopra, a sociologist at the Delhi School

of Economics. And so India's suburbs have developed into little

escapist fantasies, chiefly of the professional and middle classes

who've found themselves priced out of the city centres. Yet each

city as greatly influenced its suburbia.

Delhi's coveted suburb Gurgaon, she points

out, ''has transformed into DLF City getting an urban layering over

the rustic gown.'' So Gurgaon is a strange mix of the village and

the mall, the Opel and the plowshare. Delhi is built on an imperial

theme with the concept of a centre paramount, which its suburbs

reciprocate. Gurgaon's centre, they say, is built on hyperspace-sociologists

call this the space that is occupied on cultural differences. Hyperspace

survives by cannibalising aesthetics, says Chopra. So the Corinthian

columns, cafes, and other embellishments borrowed from the city.

Mumbai's suburbs, like Andheri and Borivili,

are home not just to a strong working class but also a professional

middle class. The suburbs are in a way syncretic to the culture

of Mumbai and the strong local train network binds the city and

its suburbs in one unit. Mumbai's inner suburbs like Bandra, Juhu,

Powai, and Ville Parle are unusual in that they are home to people

you would not find in the suburbs in other cities. Many of the super

rich-film stars, producers, builders-have made their home here in

soaring, ultra-luxury apartments, the likes of which are often not

available in the city centre. So there are neo-American complexes-self-contained

townships really-with monster Honda motorcycles and Mercedes SLK's

cruising down their smooth roads. Outside these townships, built

by builders like Lokhandwala and Hiranandani, the chaos of Mumbai

reigns supreme.

Kolkata's suburbia is evolving with the marshy

Salt Lake encroaching over more marshes to the city's east and north-east.

And the typical residents of these expanding marshlands are the

retired parents of salaried, non-resident Calcuttans who regularly

pump in more greenbacks than Indian currency to see this new Kolkata

take wing.

Chennai's chief suburb, Tambaram, is a proper

residential area well-connected by the city, particularly by its

arterial railway network. It takes a mere 30 minutes to chug your

way into Chennai Central. Tambaram has a strong middle-class and

professional composition, much like the Mumbai suburbs, and shares

its space with a host of manufacturing units.

Bangalore's windswept suburbs are occupied

by middle and upper-rung professionals, who work in the shiny new

office complexes that have sprung up where there were once rose

gardens and coconut groves. Whitefield, once a haven for retired

defence officers and the occassional chicken farmer, today houses

some of the best known names in the tech business: GE, Wipro, Bell

Labs, and Lucent, to name a few. Like Gurgaon, Whitefield is surrendering

to gentrification as many of the old farmers are selling out and

raking in their windfalls as land prices soar.

Malls. Condominiums. Clubs. Is this the way

of the future for India's suburbia? It might look that way, but

it's impossible to ignore the 'real' India outside the gates. Life

may he hectic and promising for the achievers who flood suburbia.

But their world will remain within their gates. Outside, they will

be dodging that cow and jarring their suspensions on the rutted

outer roads. Like our cities, suburbia's culture will echo all the

contradictions of the new India.

-Moinak Mitra

|