|

|

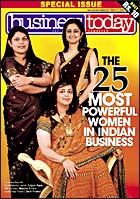

Rural mall: One of the 47,000 such haats that

dot India

|

Saunda Haat

Meerut District, Uttar Pradesh, February 2

Santari

Devi, 54, is busy looking for new designs of "paajeb"

(silver anklets), rifling through the box in which the jeweller

keeps his stock. Suman, her 18-year-old daughter is to be married

in March, and the family (other members here include husband Madan

Singh and daughter Babli) are out shopping for the trousseau.

They haven't chosen to shop in the nearest town, Muradnagar, though;

instead, they are here at Saunda Haat. The family works the fields

and mill of a sugarcane farmer in Saunda. There's work for nine

months of the year, a monthly income of between Rs 8,000 and Rs

9,000, and the family saves around Rs 30,000 to Rs 40,000 a year,

money that will run the household, pay off debts, and fund the

weddings of the daughters. Santari trusts the jeweller; she has

bought from him in the past (for the weddings of two other daughters).

"I know his (the jeweller's) family," adds Singh.

Residents of at least four villages visit

Saunda Haat every Thursday, as do merchants from the same villages,

even the nearest big town, Muradnagar. There are around 60 stalls

in the haat selling everything from groceries to apparel to kitchenware

to fresh produce. Few of the brands are familiar, Parle G, Tiger,

Dabur Lal Dant Manjan, Parachute, and Lifebuoy. Most aren't. "Being

a wholesale market, this haat is cheaper than the shops in the

villages which are anyway few," says Chowdhary Vedpal, a

member of the Muradnagar Panchayat, adding that the haat does

business of Rs 60,000 every week.

Saunda Haat is one of 47,000 that dot India,

serving the needs of around 70 per cent of India's rural population

of 742 million. According to the National Council for Applied

Economic Research (NCAER) such haats do business worth Rs 100,000

crore every year. "Most of these haats have been in existence

for the past 100 years," says Pradeep Kashyap, Managing Director,

mart, a rural-marketing consultancy. "They haven't lost their

relevance because the consumers they cater to remain untapped

by the organised industry."

| THE THING ABOUT HAATS |

»

Accessible and affordable

» Over

47,000 held annually across India

» Average

no. of stalls: 200

» Average

no. of visitors: 1,000-3,000 (15-20 per cent are women)

» Over

half the visitors at haats have shopping lists

» Average

daily sales: Rs 50,000-200,000

» Each

haat caters to customers from between five and 50 villages |

According to Census 2001, there are 6,38,365

villages in India; a study by the Federation of Indian Chambers

of Commerce and Industry estimates that 35 per cent of these have

no shops. Even consumer products companies with enviable reach

such as HLL and ITC have not been able to go beyond the top 250,000

villages. "We reach only around 2 lakh villages through our

regular distribution network and an additional 34,000 through

the e-choupal programme," says S Sivakumar who heads ITC's

agri-business division. "The rest of the rural India is out

of our reach."

Inaccessibility is one reason why; 60 per

cent of India's villages is not connected by all-weather roads

and 80 per cent does not receive regular power supply. Low population

density is another. Census 2001 indicates that the population

in over 45 per cent of India's villages is between 500 and 2,000

and in another 42 per cent, below 500. Then, the per capita income

of consumers in these rural markets, between Rs 1,000 and Rs 8,000

a month, according to IRS 2005, is also low. "The cost of

setting up retail network in these areas would be more than the

business generated," says Sivakumar. "Unit sales in

these villages are so small that it doesn't make sense to set

up an independent distribution and retail network," adds

an HLL spokesperson.

Haats gain significance in this backdrop.

These are, essentially, gather-and-disperse rural supermarkets

held mostly once a week. "Haats are the only centre for commercial,

cultural and social activity for the not-so-connected parts of

the country," says Pradeep Lokhande, Chairman, Rural Relations,

a Pune-based rural marketing agency. No big-ticket purchases happen

in these markets simply because liquidity is an issue for rural

consumers. "Shopping for expensive items like durables or

automobiles happens only once in a year, usually after the harvest

season when these consumers have cash to spare," says Priya

Monga, Business Head, Rural Communication and Marketing. Such

transactions happen in mandis, which are different from haats;

they happen once a year after harvests.

Despite such constraints, the rural market,

especially for fast moving consumer goods (FMCGs), apparel, footwear

and fuel, is bigger than the urban market for the same products.

According to mart, the size of rural FMCG market was around Rs

65,000 crore in 2002; the current size of the organised FMCG market

is only around Rs 55,000 crore. "That's mainly because around

60 per cent of the goods sold in rural markets, mainly haats,

are manufactured locally and their contribution remains unmeasured,"

explains Kashyap. Rural India is a big market for durables (Rs

5,000 crore) but haats are not the relevant markets for these.

Says Girish V Rao, Vice President, Sales, LG: "Over 40 per

cent of our total sales comes from rural markets but these sales

mainly happen during the harvest and festive season."

The true potential of haats as points of

sales has not yet been explored by marketers, says Monga. "Around

50 per cent of rural India has no access to traditional media,

thereby limiting the points of interaction with rural consumers.

Haats can be used as media platforms for marketing and promotion,"

she says.

Some banks and insurance companies, in fact,

are already looking at such opportunities. Life Insurance Corporation,

which sells 35 per cent of its policies in rural India, is looking

at haats as premium collection centres for groups of four or five

villages. "Almost 50 per cent of our agents work in rural

markets but because of infrastructural problems collecting premiums

becomes a major problem," says A K Shukla, Chairman and Managing

Director, LIC explaining the logic behind this move.

Meanwhile, Santari Devi and Suman are done

with their shopping. Suman wants to pick up some nail-polish and

lipstick for herself but her father is furious.

"Your husband will be ruined if you

squandered his money like this," he thunders. "I am

spending my own money," she shrugs. "Why should anybody

complain?". And she is off running towards the small pushcart

selling the stuff.

|