|

COVER STORY

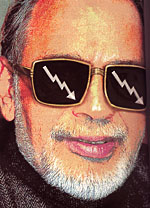

Mr Hegde

Why Are Our Exports shrinking?Are we picking the wrong products? Chasing the wrong global markets?

Targeting the wrong end of value-addition? Relying on the wrong policies? Why is India's

exports ship threatening to sink mid-sea?

By Rohit Saran & Rukmini Parthasarathy

What a fall there was, my

countrymen. Just 2 years ago, its exports sector was the star performer of the

newly-reformed, and still-reforming, Indian economy. The bumper growth of 72 per cent

between 1993-94 and 1995-96 in the dollar value of products and services shipped, flown,

trucked, and even electronically transmitted to global markets inspired heady visions of

an export-led blast-off into the rarefied orbit of double-digit economic growth. CEOs went

to bed every night dreaming of years of exponential growth, and no one sneered when the

Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) set corporate India's sights on an export target of

$83 billion by 1998-99. What a fall there was, my

countrymen. Just 2 years ago, its exports sector was the star performer of the

newly-reformed, and still-reforming, Indian economy. The bumper growth of 72 per cent

between 1993-94 and 1995-96 in the dollar value of products and services shipped, flown,

trucked, and even electronically transmitted to global markets inspired heady visions of

an export-led blast-off into the rarefied orbit of double-digit economic growth. CEOs went

to bed every night dreaming of years of exponential growth, and no one sneered when the

Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) set corporate India's sights on an export target of

$83 billion by 1998-99.

Today, those dreams lie shattered. Confidence has given way

to crisis. And hopes have been slaughtered by hard reality. ''We will be lucky if exports

cross even $36 billion in 1998-99,'' says Bibek Debroy, 43, the Director of the

Delhi-based Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies. Indeed, the first-quarter

performance in 1998-99 has been dismal, with exports recording a fall of 5.79 per cent in

the period between April and June, 1998, over the same period of 1997. Since exports

account for 10 per cent of India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), this decline of more than

5 per cent will, in a single blow, subtract 0.5 percentage points from the overall growth

rate-apart from reducing the foreign exchange available to buy goods and services abroad.

Whodunit?

Who, or what, stopped India's exports machine? The apparent

culprit seems to be the Great Asian Market Meltdown, which began in June, 1997, and is yet

to end. The resultant mayhem in global currency markets, combined with the collapse of the

East Asian economies, has garrotted global demand growth, dislocated trade flows, and

dried up markets overnight. And worse may follow if China devalues the renminbi, which

policy-makers now consider inevitable. With global trade on a downswing, Indian exports

are bound to suffer. Besides, sharply devalued currencies will make the East Asian nations

extremely price-competitive in the global marketplace once their economies recover,

further throttling exports. Take away Asia, and exports should recover. Right?

"Price concessions are

keeping India's exports stuck at the low end of the market."

B Bhattacharyya,

Dean, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade |

Actually, the Asian crisis is more of a scapegoat. To

be sure, it may account for a severe slowdown in exports growth in 1998-99. But it cannot

be used to explain a slump that actually began in 1996-97. In that year, Asia was booming,

global trade volumes were skyrocketing, the rupee had depreciated by 6.10 per cent against

the US dollar, and inflation in manufactured products had slipped to 4.01 per cent-four

factors that should have sent India's exports into overdrive. Instead, exports went into a

free fall, plunging from 20.07 per cent in 1995-96 to 4.46 per cent in 1996-97.

Policy-makers have been hard-pressed to explain this decline.

And that basic lack of understanding has led to muddled policies. The Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Administration has announced two major export polices this year: the annual revision to

the Export-Import (ExIm) Policy in April, 1998, and a package of incentives in August,

1998. Neither offers more than procedural simplifications, which should have been a

routine behind-the-scenes affair. In any case, such simplifications have rarely been

translated into a reduction of red-tape or harassment at the ground level. Worse, both

packages continue the traditional reliance on incentives and other sops to bolster export

performance. Points out T.K. Bhaumik, 48, Senior Director, CII: ''India has never had an

export strategy. What we had in the name of an export policy was no more than a charter of

incentives.''

Sadly, exporters are displaying the same myopia, with a

majority of them clamouring for more incentives. In fact, 48 per cent of those surveyed by

a BT-AIMS poll of 50 CEOs in 5 metros believe that the best way to boost exports growth is

to provide more fiscal sops. Unfortunately, in today's super-competitive global

marketplace, incentives are not enough for a country, or its exporters, to succeed. To

explore the causes of endemic export recession and analyse why export polices have failed,

BT dissected the country- and commodity-composition of India's merchandise exports. The

export intensity of the country's largest corporations were also examined. The findings

are grim. There are fundamental structural problems with India's exports-problems that

won't be solved by the policies that have been announced. Indeed, if the current trends

persist, India's export crisis will continue long after the debris from the East Asian

collapse settles.

Why Have India's Exports Collapsed

Dramatically?

"India has never had an

export strategy. What it had was a charter of incentives."

T K Bhaumik,

Senior Director, CII |

Because depreciation-driven growth has ended-as was

inevitable. The revival of 1992-93, when exports recovered from an absolute fall of 1.08

per cent in 1991-92 to a growth of 3.28 per cent, was powered by massive devaluation of

the rupee: of 36.60 per cent in 1991-92, and of 18.11 per cent in 1992-93. Since each

dollar now fetched more rupees, earnings per unit soared by 26.32 per cent and 14.07 per

cent, respectively, in those 2 years. Gleeful exporters undercut the prices of their

global competitors, none of whom had the luxury of a currency that had depreciated as

much. Of course, these were the years that saw the most spectacular trade reforms: average

Customs duties were slashed from 127.70 per cent in 1991-92 to 71 per cent in 1993-94, and

a host of quantitative restrictions was dismantled, helping exporters. The momentum

generated in the process propelled exports growth to a phenomenal 19.56 per cent per annum

between 1993-94 and 1995-96.

By 1995-96, however, there were ominous signs of the boom

ending. Although export volumes had surged by an astounding 31.29 per cent over 1994-95,

earnings per unit of exports fell by 2.10 per cent in rupee terms, and by 7.01 per cent in

dollar terms. Obviously, price-competitiveness had peaked. The virtually unchanged

commodity composition of the exports basket, not to mention the absence of any perceptible

improvements in quality, ushered in the inevitable fall in exports growth in 1996-97, even

though world trade growth was still healthy at 6.60 per cent in volume terms. However,

since the still-to-slacken demand in the domestic market secured an industrial growth rate

of 8.60 per cent in 1996-97, the fall in exports growth did not pinch.

However, by 1997-98, both the internal and external

environments had changed dramatically. East Asia imploded, global trade expansion slowed

down, and demand at home sagged. Exports growth contracted further to a meagre 2.66 per

cent in 1997-98, from where it has now slipped into a recession. Tellingly, even the 15.07

per cent depreciation of the rupee against the dollar between March, 1996, and March,

1998, did not stave off the decline.

The lesson? Depreciation-induced growth is inherently

temporary. It is also misleading, because gains from such growth accrue only in rupee

terms, whose intrinsic value has fallen anyway. For instance, in 1993-94, rupee earnings

per unit of exports rose by 12.48 per cent, but in dollar terms the growth was only 3.52

per cent. By contrast, in 1994-95, rupee earnings per unit of exports rose by 4.32 per

cent while dollar earnings rose by 8.17 per cent. Clearly, in dollar terms, 1994-95 was

the most rewarding year of the 1990s for exporters. Not coincidentally, the rupee

depreciated by only 0.13 per cent that year.

"Sector by sector, the policy

of small-scale reservation has murdered Indian exports."

B Debroy,

Director, Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Contemporary Studies |

THE POLICY POSITION. Rightly, Union

Commerce Minister Ramakrishna Hegde has refused to force a more-than-gradual depreciation

of rupee to buoy exports. In a floating exchange rate regime, it is difficult for

governments to engineer orderly depreciation. In any case, with the continuing turmoil in

global currency markets and the seemingly never-ending political uncertainty at home,

there may be no need for the government to engineer what the market will achieve

naturally. The rupee has already slipped past Rs 43, a depreciation of 8.71 per cent since

April, 1998. But this is unlikely to provide more than a temporary fillip to exports

growth. As past experience demonstrates, a sliding currency discourages exporters from

making the quality improvements necessary to build long-term competitiveness. Concurs

Rajesh Chadha, 43, Reader (Economics), Hindu College and Advisor, National Council of

Applied Economic Research: ''When you are not inherently competitive, artificial

pump-priming of exports, using more than market-dictated depreciation, will not yield

sustainable growth.'' Even in the short run, a depreciation-powered boost to

price-competitiveness may be marginal, since the value of most East Asian currencies has

been eroded between 50 and 175 per cent in the past 12 months.

Although the use of depreciation as a policy lever has been

ruled out, policy attention remains fixated on price. The recently announced rescue

package for exports comprises incentives like a 2 percentage point reduction in

pre-shipment credit and the extension of tax-holidays for export-oriented units from 5 to

10 years. Argues B. Bhattacharyya, 55, Dean (Research), Indian Institute of Foreign Trade:

''Price concessions will ensure that Indian exporters remain stuck at the low end of the

market spectrum. They will provide little stimulus for tackling problems of quality and

delivery, which are endemic to Indian exports.'' A better course of policy action would be

to chart out a strategy for changing the commodity composition of exports, which are

highly skewed towards low-technology and traditional products.

Which of India's Exports Have Been

Affected the Most?

Those with the largest share in India's exports basket. While

the growth rates of virtually all big-ticket export items decelerated sharply between

1994-95 and 1997-98, the decline was most catastrophic for leather products and

electronics goods, where exports fell by 8.46 and 10.83 per cent, respectively, in

1997-98. Textiles and fabrics, which account for 11.59 per cent of the country's total

exports, also collapsed, with growth plummeting from 26.24 per cent in 1994-95 to 0.59 per

cent in 1997-98. The world didn't buy less, however: textile exports from China shot up by

25 per cent, proving that the country's decline came from a lower marketshare.

Even more ominous was the erosion in the unit value

realisation from key exports. A commodity-wise study of exports between 1987-88 and

1996-97 reveals that the products with the fastest growth in export volumes were those

with the maximum fall in dollar realisation per unit. For instance, the volume of rice

exports rose by 22.81 per cent during the 9-year period, even as its unit value

realisation tumbled by 6.74 per cent. A host of other primary exports, including spices

and cashews, exhibits the same trend. Manufactured products fared no better. Exports of

engineering goods, for instance, grew by 18.94 per cent in volume, but unit value

realisation fell by 1.27 per cent in the same period.

The wide wedge between volume growth and unit realisation

reflects both the extent of price competition that the majority of Indian exports face,

and the low rung of the value chain that they occupy. Take gems and jewellery, the

single-largest item in the exports basket. Despite commanding a 12.60 per cent share of

the market for a product that is inherently high-priced, exporters have been unable to

extract better prices. Unit value realisations have remained virtually stagnant over the

last decade. Clearly, the absence of even a single Indian brand in the global market has

relegated products from the country to the low margin-low value segment.

THE POLICY POSITION. Trade policies have

perpetuated the dominance of low-value, traditional items in the trade basket. In

December, 1995, the Union Commerce Ministry had identified 15 products as priority items

for export promotion. But 11 of them were either primary products or traditional

manufactured goods. Software, India's fastest growing category of exports, did not even

figure in the list of priority items. Complains CII's Bhaumik: ''The biggest hurdle to

exports growth are not the non-tariff barriers but the non-technology barriers, an issue

that export policy has consistently failed to address.''

In fact, Commerce Minister Hegde's vision, as unveiled in the

ExIm Policy revision in April, 1998, attempts no radical departure from the past.

Agriculture and textiles remain thrust areas, although electronics and engineering

goods-and, for the first time, branded jewellery-are also to be accorded priority. But the

concurrent promotion of agriculture and hi-tech manufactured products will run into an

inherent problem of conflicting interests. For, while depreciation is an unmixed blessing

for traditional exports, given their low import content, it will hurt high-value-added

manufactured products, as their import intensities are climbing. The real requirement:

product-specific, market-focused strategies, the lack of which is evident in the fall of

India's exports of textiles and readymade garments just when the US and Europe have been

phasing out the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) quotas. Quantitative restrictions prevent the

makers of readymade garments from importing better quality textiles, thus inhibiting

quality upgradation of the kind that has enabled South Korea to build a global market in pret-a-porter

clothes made from imported fabrics.

More |