AUDITSCAN

All Weighed Down:

The Soaring Staff Costs of Our National Carriers

One of the first Indian companies to go

on-line, ICICI is now poised to take a major leap in the Net-based trading

business.

By M.V.

Ramakrishnan

''Sky is the limit!'' is a familiar

expression that eminently describes the business of an airline. In recent

years, it has also been an accurate descriptor of the staff costs of

Indian Airlines and Air India. One has been aware of this in a general

way, but just how high these costs have tended to soar, and why, has been

graphically brought out by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG)

in a Central Commercial Audit Report submitted to both Houses of

Parliament on May 4, 2000. The report contains some concise tables, which

play host to some very illuminating numbers.

The Indian Airlines Story

The wages of excess

IA:

Trend Of Staff Costs shows the expenditure incurred by Indian Airlines

(IA) on its staff between 1993-94 and 1998-99, and the corresponding

operational- and total-expenditure, and fleet strength. During this

period, the airline's staff costs increased by 207 per cent, and its cost

per employee by 209 per cent. The staff cost per Revenue Tonne Kilometre (RTKm)-a

yardstick that measures the actual traffic carried on which revenue is

earned-increased from Rs 4.11 lakh in 1993-94 to Rs 12.34 lakh in 1998-99.

And the proportion of staff costs to the operational expenditure increased

from 15 per cent to 28 per cent in the same time frame. IA:

Trend Of Staff Costs shows the expenditure incurred by Indian Airlines

(IA) on its staff between 1993-94 and 1998-99, and the corresponding

operational- and total-expenditure, and fleet strength. During this

period, the airline's staff costs increased by 207 per cent, and its cost

per employee by 209 per cent. The staff cost per Revenue Tonne Kilometre (RTKm)-a

yardstick that measures the actual traffic carried on which revenue is

earned-increased from Rs 4.11 lakh in 1993-94 to Rs 12.34 lakh in 1998-99.

And the proportion of staff costs to the operational expenditure increased

from 15 per cent to 28 per cent in the same time frame.

In

absolute terms, IA's annual expenditure on staff has increased by Rs 590

crore in this period. To cope with the constantly rising expenditure, IA

increased its fares every year from 1994 to 1998. And staff costs

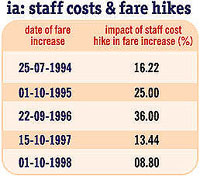

accounted for between 9 and 36 per cent of such hikes (IA: Staff Costs

& Fare Hikes). In

absolute terms, IA's annual expenditure on staff has increased by Rs 590

crore in this period. To cope with the constantly rising expenditure, IA

increased its fares every year from 1994 to 1998. And staff costs

accounted for between 9 and 36 per cent of such hikes (IA: Staff Costs

& Fare Hikes).

The reduction in staff strength was quite

marginal in these years: more than 540 new posts were created, including

271 in the executive cadres. But the strength of the fleet declined

steeply, from 54 to 41.

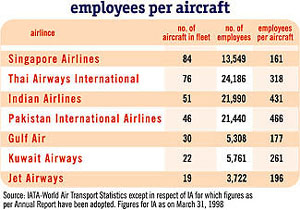

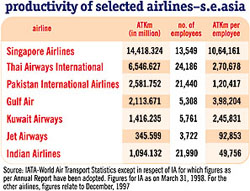

Among the major airlines functioning in the

South-East Asian region, the number of employees per aircraft in IA was

second only to Pakistan International Airlines (Employees Per Aircraft).

And, IA's productivity in terms of the Available Tonne Kilometre (ATKm)-indicating

the maximum traffic that can be carried-was the lowest (Productivity Of

Selected Airlines-S.E. Asia).

The

audit review notes that senior-level posts were added arbitrarily. A dozen

posts for directors were sanctioned between 1994 and 1998 without adequate

justification, raising the number of IA's directors from 18 to 30. Six of

them were created by upgrading six posts of general managers, and these

six posts of general managers were, again, sanctioned. More than 130

retired employees were hired between 1995 and 1999 on a contract basis

with dubious perks, merely for performing routine jobs. And, while there

was a substantial underutilisation of manpower all round, huge sums were

paid as overtime allowance, resulting in the Budget estimates being

invariably exceeded every year. The

audit review notes that senior-level posts were added arbitrarily. A dozen

posts for directors were sanctioned between 1994 and 1998 without adequate

justification, raising the number of IA's directors from 18 to 30. Six of

them were created by upgrading six posts of general managers, and these

six posts of general managers were, again, sanctioned. More than 130

retired employees were hired between 1995 and 1999 on a contract basis

with dubious perks, merely for performing routine jobs. And, while there

was a substantial underutilisation of manpower all round, huge sums were

paid as overtime allowance, resulting in the Budget estimates being

invariably exceeded every year.

Incentivised to Work

The

period between 1995-96 to 1998-99, at IA was marked by steeply escalating

expenditure on various Productivity-Linked Incentives (PLI), for which the

management entered into separate agreements with various employees' unions

and associations. The rationale behind these incentives was to prevent the

luring away of skilled and experienced pilots and engineers, by

newly-established private airlines. Consequently, the aspirations of other

employees also had to be considered. The expenditure on PLI was estimated

to be around Rs 150 crore per annum, but it was expected to generate

additional revenue in excess of Rs 200 crore per annum. The

period between 1995-96 to 1998-99, at IA was marked by steeply escalating

expenditure on various Productivity-Linked Incentives (PLI), for which the

management entered into separate agreements with various employees' unions

and associations. The rationale behind these incentives was to prevent the

luring away of skilled and experienced pilots and engineers, by

newly-established private airlines. Consequently, the aspirations of other

employees also had to be considered. The expenditure on PLI was estimated

to be around Rs 150 crore per annum, but it was expected to generate

additional revenue in excess of Rs 200 crore per annum.

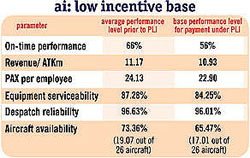

However, a serious flaw in the whole set-up

was that the base performance levels at which PLI would come into play

were fixed below the existing actual average performance levels (IA: Low

Incentive Base). In other words, some extra money would be paid even for

maintaining status quo. Surely, the management must have realised at the

outset that the massive outlay on PLI would not be matched by any

impressive spurt in productivity.

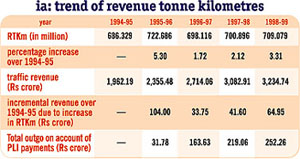

In

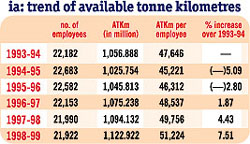

the event, a dismal scenario followed. Productivity in terms of ATKm and

RTKm improved only marginally between 1995-96 and 1998-99, and the

additional revenue earned fell far short of the estimated Rs 200 crore per

annum. However, the expenditure on PLI was much higher, and even exceeded

Rs 200 crore per annum in the last two years (IA: Trend Of Available Tonne

Kilometres and IA: Trend Of Revenue Tonne Kilometres). In

the event, a dismal scenario followed. Productivity in terms of ATKm and

RTKm improved only marginally between 1995-96 and 1998-99, and the

additional revenue earned fell far short of the estimated Rs 200 crore per

annum. However, the expenditure on PLI was much higher, and even exceeded

Rs 200 crore per annum in the last two years (IA: Trend Of Available Tonne

Kilometres and IA: Trend Of Revenue Tonne Kilometres).

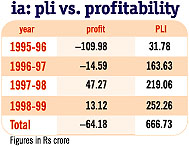

That

apart, IA's RTKm was consistently lower than its ATKm. A PLI agreement

with one of the unions in 1997 was given retrospective effect from a

date when a similar earlier agreement was still valid. This overlapping

led to an unjustifiable (incremental) expenditure of Rs 37 crore. What

emerged as a result of all these was an anomaly where PLI costs added up

to Rs 667 crore in the four years ending 1998-99, even as the organisation

suffered a net overall loss of Rs 64 crore (IA: PLI Vs. Profitability). That

apart, IA's RTKm was consistently lower than its ATKm. A PLI agreement

with one of the unions in 1997 was given retrospective effect from a

date when a similar earlier agreement was still valid. This overlapping

led to an unjustifiable (incremental) expenditure of Rs 37 crore. What

emerged as a result of all these was an anomaly where PLI costs added up

to Rs 667 crore in the four years ending 1998-99, even as the organisation

suffered a net overall loss of Rs 64 crore (IA: PLI Vs. Profitability).

Apart

from the performance-linked incentives, IA also paid a special

productivity allowance and a fixed productivity allowance to certain

categories of staff without linking them with performance at all. And

defying all logic, it also gave, to certain administrative and technical

officers and engineers, an allowance for 'out-of-pocket expenses' every

day merely for attending office on working days, and an 'experience

allowance' merely for being experienced! Apart

from the performance-linked incentives, IA also paid a special

productivity allowance and a fixed productivity allowance to certain

categories of staff without linking them with performance at all. And

defying all logic, it also gave, to certain administrative and technical

officers and engineers, an allowance for 'out-of-pocket expenses' every

day merely for attending office on working days, and an 'experience

allowance' merely for being experienced!

The Air India Story

More

Wages of Excess More

Wages of Excess

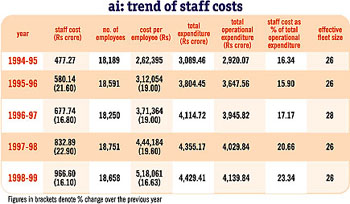

AI: Trend Of Staff Costs shows the trend of

expenditure on staff in Air India (AI) from 1994-95 to 1998-99, the

corresponding operational and total expenditure, and the fleet strength.

Staff costs rose steeply from 16.34 per cent

of operational expenditure to 23.34 per cent, during this period, although

the number of employees remained more or less the same. In terms of

absolutes, the annual expenditure on staff went up by Rs 490 crore.

AI's

productivity, however, remained the lowest among the major international

airlines. In terms of parameters like employees per aircraft, passengers

per employee and RTKm, AI's figures were the worst (Productivity Of

Selected Airlines). AI's ATKm-level declined from 2,615 million in 1995-96

to 2,541 million in 1998-99. And its RTKm, from 1,620 million to 1,520

million. As in the case of IA, the RTKm was considerably lower than the

ATKm. AI's

productivity, however, remained the lowest among the major international

airlines. In terms of parameters like employees per aircraft, passengers

per employee and RTKm, AI's figures were the worst (Productivity Of

Selected Airlines). AI's ATKm-level declined from 2,615 million in 1995-96

to 2,541 million in 1998-99. And its RTKm, from 1,620 million to 1,520

million. As in the case of IA, the RTKm was considerably lower than the

ATKm.

Since 1990 there had been a prolonged delay

in arriving at wage settlements, causing severe turbulence in

management-employee relations. Some agreements could be settled only in

1996-98, but, meanwhile, the management decided to pay certain costly

allowances, some of which had built-in anomalies.

Traditionally AI's pilots were eligible for

hotel and lay-over allowances based on the time spent by them on duty away

from their stations. As there was a tendency to abuse this, in 1994, the

system was replaced by one of 'hourly payment' based on the actual flying

time. A related provision was that the line earnings of senior pilots

should not be less than that of their juniors, and in such an event, the

difference had to be made good in terms of hours, if the seniors had been

available for duty. All this looked rational on the surface, but in

practice, the new system was more expensive than the earlier one. The

extra expenditure was estimated at about Rs 17 crore per annum. This goes

against the idea of effecting economies. As the CAG puts it, senior pilots

were paid at higher hourly rates, and they earned more for not flying than

their juniors did for flying!

In 1995, a decision was taken to abandon the

shortfall idea. This, however, did not happen. Rather, its scope was

enlarged, giving a similar compensation to AI's regular pilots vis-a-vis

retired pilots engaged on a contract basis. A fresh agreement in 1998

continued the system, only requiring that the shortfall must be computed

on a six-monthly basis instead of every month, for whatever it was worth.

More

on Incentives More

on Incentives

In 1996 the airline introduced a PLI scheme,

covering about 16,200 out of its 18,700 employees. The airline's

expenditure on PLI during 1996-99 was Rs 356 crore. Just as in the case of

IA, the minimum levels of performance for PLI to come into play was fixed

at below the actual average existing performance levels (AI: Low Incentive

Base). Thus, this scheme was also flawed from the start. Though the

management conceded, in 1999, that the base levels needed to be revised as

they were too low, there has been no move in that direction.

'Aircraft

availability' is one important criteria for the payment of PLI. The

management claimed that with the fleet strength remaining at 26, aircraft

availability had gone up from 17.14 in 1996 to 25.60 in 1998. But aircraft

utilisation in the case of Boeing 747-200 and 747-500 actually declined

during the period (AI: Aircraft Utilisation). The audit view is that the

choice of parameters was not sufficiently broad-based and did not reveal

the true overall productivity of airline. 'Aircraft

availability' is one important criteria for the payment of PLI. The

management claimed that with the fleet strength remaining at 26, aircraft

availability had gone up from 17.14 in 1996 to 25.60 in 1998. But aircraft

utilisation in the case of Boeing 747-200 and 747-500 actually declined

during the period (AI: Aircraft Utilisation). The audit view is that the

choice of parameters was not sufficiently broad-based and did not reveal

the true overall productivity of airline.

Finally, the audit report underlines the

flimsy nature of some special allowances. For instance, a 'productivity

allowance' for general cadre officers was introduced in 1995 with

retrospective effect from 1993, without being linked with performance

levels. When the PLI scheme was extended to the general cadre officers in

1996, it clashed with the existing productivity allowance, which was not

withdrawn and amounted to Rs 71 crore during 1996-99.

A bizarre benefit existing from 1974 is a

'special compensatory allowance' paid to general category officers.

Eloquently attempting to justify its existence by comparing it with a

similar allowance in the government, AI's management pleads:

''Compensatory allowance is granted to employees working in remote

localities, border areas and difficult areas. A similar situation is in

Air India, whereby the officers have to work in difficult areas such as

the tarmac in the burning hot sun in summer and in the cold whilst in

winter....'' Should one stand up and cheer: Bravo, Air India?

About the Author

M.V. Ramakrishnan, who served in

the Indian Audit & Accounts Service from 1957-92, has conducted

various investigative audits, including those of the economic ministries

in Delhi and the Indian High Commission in London. After serving as the

Additional Deputy CAG Of India from 1990-92, Ramakrishnan was the

Consultant to the CAG of India from 1992-93, and the Consultant to the PTI

(Administration & Finance) from 1993-94.

|