|

Around

the first week of may, Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams received a

most unusual visitor. Going by the name of Dayan Ahron Dovid Dunner,

the gentleman was an ultra-orthodox rabbi from north London, who

had specially made the trip to Tirupati to watch the temple's tonsuring

'factory' at work. Rabbi Dunner watched as hordes of men and women

queued up to get their heads shaved, and he watched as their hair

got collected and bundled in gunny bags. Through a translator, he

went on to interview barbers, donors and temple guides, and noted

down everything he heard. Soon thereafter, Rabbi Dunner sent a report

to Rabbi Sholom Elyashiv, leader of the Orthodox Lithuanian Torah

Jewry in Israel.

On May 12, Rabbi Elyashiv issued a ruling that

sent the sedate world of wig making into a turmoil. He decreed that

wigs made of hair of Hindu women from India were not kosher and,

therefore, must not be worn by married Jewish women, one of the

biggest consumers of natural hair wigs, since their religion forbids

them from publicly displaying their own hair. Orthodox Jews from

around the world made frantic phone calls to their wig suppliers

to find out if the hair in their wigs had originated from India.

Some of the more virulent ones in places like New York actually

heaped up hairpieces from India and set them on fire. M.M. Gupta,

Chairman of the Chennai-based Gupta Enterprises, which exports Rs

85 crore worth of hair, quickly took a flight to the US in his bid

to douse the wildfire. "We have explained that people tonsure

their hair as a mark of respect to the gods, and it should not be

considered as an offering to the idol," says Gupta.

|

| Assembly-line shaving of heads in action at

Kalyana Katta, the main tonsuring area in the temple of Tirupati,

which employs 600 barbers |

The rabbis may call Gupta's defence hair-splitting,

but the fact is India's Rs 500-crore hair export industry could

take a hit if Jews around the world decide to heed to Rabbi Elyashiv's

call. There are an estimated 7 lakh Jewish women customers, who'll

overnight switch to other kinds of wigs. At the moment, though,

exporters like Gupta are sanguine. In fact, the industry is growing

at 20 per cent a year, and next year could be worth Rs 600 crore.

"Every time we've been hit by a crisis, we have come out stronger,"

says Gupta.

Locked In

Thank the unique quality of Indian hair as

much as the resilience of entrepreneurs. Expert wig makers consider

Indian hair second only to European hair in terms of texture and

sheen. But since European hair is in short supply and in any case

Jewish women are forbidden from wearing those too because they are

considered too glamourous, the Indian variety manages to command

a premium. For example, wigs made of hair from India sell at prices

between $1,000 (Rs 45,000) and $3,000 (Rs 1.35 lakh), depending

on the length and style. Other Asian hairpieces such as Chinese

(incidentally, China is the biggest exporter of processed hair)

fetch significantly less-$300 to $700 (Rs 13,500 to Rs 31,500).

|

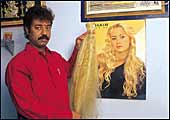

| Chennai-based exporter K.A.G. Raju poses next

to a poster of a Brazilian model, who he claims is sporting

hair processed by his company |

The biggest source of organised supply of hair

for exporters in India are temples, and among them, Tirupati. Every

year, a staggering 8 million people come to this temple, India's

richest, to get themselves tonsured, and last year the temple authorities

sold 2,80,000 kilos of hair for Rs 28 crore. This year, earnings

are expected to go up to Rs 30 crore.

Despite the trade's dowdy image, it is fascinatingly

organised. At Tirupati, for example, the hair gets graded into five

varieties, which fetch anywhere between Rs 20 and Rs 7,000 per kilo.

(You'd never guess what happens to shorter hair: converted into

amino acid supplement L-Cystein, they find their way into everything

from chocolates to infant food.) About 600 barbers on the temple's

payrolls work in shifts round the clock, literally mowing down the

serpentine queues with a lighting fast shave that takes an average

of four minutes. The business is so lucrative for the temple that

it accounts for a quarter of all its earnings, having grown from

Rs 7 crore in 1988-89 to Rs 28 crore last year. All hair at the

temple is bought by a powerful lobby comprising 12 of the biggest

exporters, who resell it to smaller players.

|

| Your Wig House of V. Hari (L) and M.A. Rao

specializes in hand-made wigs that fetch between Rs 5,000 and

Rs 15,000 |

|

| Workers at Chennai's K. Arumugam & Co. process

hair destined for markets in North and South Americas, Europe

and Korea |

A great deal of the processed hair from India

is sent to China, where it is processed and re-exported. But some

exporters such as K.A.G. Raju of Chennai-based K. Arumugam &

Co. prefer to sell to North and South Americas, Middle East, Korea,

and Europe. Raju also does not depend on Tirupati for supplies,

instead travels 20 days a month to buy from elsewhere. Interestingly

enough, temples account for just 10 per cent of hair purchased by

exporters. The remainder comes from salons and hair that rag pickers

manage to collect from garbage dumps. The village of Bhagyanagar

in Hospet, Karnataka, has 2,000 families that eke out a living sorting

hair collected by rag pickers.

Entrepreneurs like Gupta say that India could

have built a bigger industry but for the lack of investments. China

has at least 40 large players in the Hainan province, with one company

alone, Xinzheng Tianyuan Hair Products Co., raking in excess of

$20 million. "My competitors 20 years ago have now become my

buyers," rues Gupta, talking of China.

For some others like Raju, the ambition is

far more modest. "More than money, I want name," says

Raju, who plans to brand his processed hair. In his office, posing

next to a poster of a blonde Brazilian model advertising a shampoo,

Raju claims with some amount of pride: "She is wearing our

hair." For that reason too, Raju reckons that the storm whipped

up by Rabbi Elyashiv will eventually blow over.

|