|

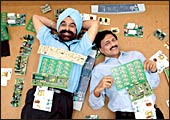

"The best of SMEs get

credit at interest rates which are at least around 175-200

basis points higher than those of blue chip large corporates"

J.S. Gujral (left), Director, and Sanjiv Narayan,

MD/ SGS Tekniks |

A

petrochemical engineer by education and entrepreneur by choice,

Nagesh Basarkar, 33, is a happy man. Core Energy Systems Pvt.

Ltd, an enterprise set up by him in 1999 with a capital of Rs

40 lakh, is growing and growing fast. In less than six months

of 2006-07, it has clocked Rs 10 crore in revenues. The tiny enterprise's

journey has been well worth the trouble. But once in a while,

Basarkar still gets to sample the constraints that bind a small

business. In January this year, for instance, four banks-including

private and public sector banks-turned down his request for a

loan. Core, which provides turnkey solutions for capital equipment

projects, had won an order worth Rs 6.2 crore from one of the

top government-backed research organisations. With impeccable

execution credentials, Basarkar felt the new order would be his

ticket to realising his dreams: A turnover of Rs 100 crore by

2010.

What was the problem? A hefty collateral

as a pre-requisite for the loan. And the collateral size? The

usual 20 per cent of the order-or a whopping Rs 1.24 crore in

Core's case. "At the rate we were growing, no way could we

have put up so much money," says Basarkar. Core has doubled

its turnover in 2005-06 to Rs 4 crore. The inland letter of credit

from his client meant little for the bankers. A new generation

private banker told Basarkar that the nervousness stemmed from

the huge size of the order, given Core's puny turnover of Rs 2.2

crore. "They did not doubt my technical capabilities of delivering

on the project. The bankers probably expect small enterprises

to grow at only 20-25 per cent and no more," he says. Basarkar's

case, though representative of the chicken-and-egg situation that

most small and medium enterprise (SME) promoters get into, did

not end in the manner it usually does for most SMEs. He did manage

to find the funds.

Lucky him. A study of 32,000 SMEs and 2,500

large corporates by rating agency, crisil, shows that SMEs have

lower access to bank funding. SMEs have a significantly low median

gearing (that is, debt as a percentage of shareholders' equity)

of 0.34 times as against 0.73 times for the large corporates,

according to CRISIL. "The difference was even more evident

when promoter loans are considered quasi-equity," says D.

Thyagarajan, Director, CRISIL SME Ratings.

THE SME SEGMENTATION

Size plays an important role in

access to credit. |

Turnover/ Status

< Rs 50 lakh

Usually run by promoters themselves, has limited manpower

and understanding of market or needs of bankers. Lack of knowledge

and awareness predominates. Has little recourse to organised

finance. Most distressed.

Rs 1-5 crore

May be mostly linked to a medium-sized or large unit or

large suppliers. Only 35-40 per cent get adequate credit.

Rs 5-25 crore

Reasonably well established, has educated management, proper

business processes and organisational structure. Books are

in order. 85-90 per cent get finance without difficulty.

> Rs 25 crore

Having attained critical size, this segment provides most

comfort to organised channels of finance. This segment is

chased by banks and others for margins that they provide.

|

Insistence on collateral, personal guarantees

and other such credit enhancements spring from the historically

high non-performing assets in the SME sector. Heightening the

caution levels are the poor information flow about the sector

and its informal business practices. "Traditionally, such

companies have been very opaque about their disclosures to banks,"

says Vijay Chandok, General Manager, ICICI Bank.

Consequently, the higher risk perception

gets factored into the cost of funds and the time taken for disbursement.

Sometimes the due diligence by banks takes as long as three to

four months. "The best of SMEs get credit at interest rates

which are at least around 175-200 basis points higher than those

of blue chip large corporates," says Sanjiv Narayan of Gurgaon-based

SGS Tekniks, which manufactures industrial electronics at its

plants in Gurgaon and Baddi. Narayan points out that even aggressive

private sector and foreign banks are of no help. "They are

willing to lend but only at bigger ticket sizes," he says.

Other channels of organised finance, whether

it is private equity and venture firms or institutions such as

Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI), are constrained

by the same factors. According to SIDBI Chairman N. Balasubramanian,

the smaller units are the most distressed ones. He splits the

SME universe into four categories on the basis of turnover and

their access to finance (see The SME Segmentation). As the enterprises

increase in size and scale, they become more sophisticated in

their business processes. "The smallest category typically

has just one to two people running the enterprise, so there is

limited manpower and little understanding of funding requirements,"

he says. Manish Gupta, Managing Director of advisory firm IndusView

Advisors, agrees. "A lot of SMEs do not maintain good books,

and then there is the management structure-typically family-run

with no second rung in place," he says.

Kunwer Sachdev, a first generation entrepreneur

who heads Su-Kam Power Systems Ltd and now has Reliance Energy

India Power Fund and Temasek Holdings as private equity investors,

explains the start-up issues. "In the early stages, accounting

or finance-related issues are often the last priority for the

entrepreneur as he is focussed on just growth in sales. Private

equity investors or banks on the other hand need assurance of

safety of their investment." Moreover, in pursuit of their

goal of high returns, VCs have a preference for scalable ventures-untried

or untested ventures; or ventures which are highly technology

oriented, difficult to replicate or have entry barriers for others.

|

"At the rate we were

growing, no way could we have put up so much money (a collateral

of Rs 1.24 crore against a bank loan of Rs 6.2 crore)"

Nagesh Basarkar

CMD/Core Energy Systems |

The other big issue in India is that of reaching

out to this granular pool of SMEs stretching across multiple industries.

"Since it is a diffused set that is being targeted, accessing

SMEs in a cost-efficient manner is a difficult task," says

Gupta. With demand far outstripping supply, Balasubramanian readily

owns that "the needs of the smaller outfits could not be

addressed appropriately, even by SIDBI". SIDBI was formed

in 1990 as a development finance institution for the sector.

Slowing down progress is the fact that there

is no published or syndicated information available on Indian

SMEs, unlike some of the other developed nations. Left with limited

options for organised finance, SME promoters often rely on their

own sources of funding such as high cost credit card loans or

approach NBFCs or unorganised money lenders. Such funds come at

a premium and affect the firm's efficiencies and competitiveness.

And the SMEs continue in the vicious cycle of small size and inadequate

finance.

Government Push

Stunted SME growth costs the nation, since

small enterprises are what drive the economy. Aware that the small

sector contributes nearly 40 per cent to the industrial output

of the country and is the largest source of employment after agriculture,

the government is planning to put in place a comprehensive legislation

by October this year (see The Big Invisible on page 100). The

intent is to push for doubling the flow of credit to this sector

from Rs 67,000 crore in 2004-05 to Rs 1,35,000 crore by 2009-10.

Meanwhile, asymmetry of information is being

tackled on two fronts. Beginning May this year, Credit Information

Bureau (India) Ltd (CIBIL) has started compiling credit histories

of enterprises. It has begun with a database of 600,000, of which

nearly 95 per cent are SMEs. "The total targeted database

could be over 1 million," says CIBIL Chairman S. Santhanakrishnan.

|

"In the early stages,

finance-related issues are often the last priority for the

entrepreneur"

Kunwer Sachdev

CEO/Su-Kam Power Systems |

In the interim, banks are also becoming more

flexible in their assessment procedures. Bankers, as seen in Core

Energy's case, have traditionally looked at financial ratios and

have lent against the security of fixed assets. Now, however,

banks are formulating alternate strategies. For example, ICICI

Bank, which has chased SME clients quite aggressively, looks at

surrogates like supply chain linkages and cash flows to evaluate

the credit worthiness of the SME entities. It has also developed

a proprietary scorecard-based model to process credit information

faster. And the result is that the SME strategic business unit

contributes 11 per cent to the bank's total fee income. This points

to the inherent bankability of the sector as a whole.

Credit rating by independent agencies is yet

another way to fill information gaps. Last year, SIDBI teamed

up with Dun & Bradstreet and CIBIL to set up the SME Rating

Agency (SMERA). CRISIL too began its SME ratings business last

year with Su-Kam and has rated some 400 firms already. SMERA has

also tied up with 16 banks, 12 of which have linked their lending

terms to the rating obtained. "With a credit rating, 50 basis

points could be shaved off from the interest rates," says

SGS' Narayan.

However, it is early days yet and the concept

has yet to catch on. "SMEs often fear that since their financials

do not reflect the correct picture, they may not get a good rating

and the same could boomerang via reduced lending," says SMERA

CEO, Rajesh Dubey. But as the good stories get around, the rationale

for transparency will gain ground and it could well lead to a

significant change in the operating environment. "This would

reduce the turnaround time for SME loans, as well as promote risk-related

lending," says Santhanakrishnan of CIBIL. "Currently,

the good SMEs are cross-subsidising the bad ones with high rates

for all," he says.

More Solutions

|

"Traditionally, small

enterprises have been very opaque about their disclosures

to banks"

Vijay Chandok

General Manager/ICICI Bank |

Apart from legislation, other measures such

as Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Small Industries (CGTSI) and

the creation of the Indonext platform (a Bombay Stock Exchange-backed

market for raising debt and equity for small businesses) augur

well. Fiscal measures such as simplification of disclosure requirements

could also help. "The disclosure requirements and accounting

methodology for recognising income as applicable to large firms,

is neither desirable nor feasible," says SMERA's Dubey.

SIDBI's Balasubramanian believes that instead

of relying on government machinery alone, private sector potential

should be tapped in targeting the smaller-sized firms. "For

credit demands up to Rs 5 lakh or so, local experts need to be

encouraged. They could serve as the link between local entrepreneurs

and the banks and could mentor the entrepreneurs on quality, technology

and finance issues," he says.

SME-oriented venture funds such as SBIC (Small

Business Investment Company) programme of us Small Business Administration

can fill the gap in private equity for SMEs. But ultimately as

ICICI Bank's Chandok says, "Efficient business models would

attract capital at competitive rates and natural competition amongst

financiers will drive prices down. In such a context, the onus

of getting cheaper finance to a large extent rests with the SMEs

themselves."

The goods news: The more progressive small

entrepreneurs already get the message.

|