|

As

fancy hotel suites go, the one at the end of the corridor east to

the bank of cramped elevators on the first floor of Oberoi Hotel

in south-central Delhi, is nothing to write home about. It's 2,000

sq ft of cavernous real estate with wall-to-wall carpets and Mughal

paintings, and a narrow corridor that has rooms on either side.

Walk into the first room to the corridor's left, and you'll find

a small workstation hugging one corner, a large three-piece sofa

with green leather upholstery sitting not too far away, near a large

quasi-French window. There are two untitled paintings on the wall

behind the workstation, one of which is hung above a shelf cluttered

with files and documents. On the whole, a rather unpretentious and

functional pad.

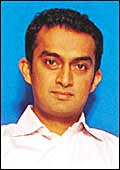

Just like its occupant, you could say, who

on this day is wearing khaki-coloured trousers, an open-collared

blue shirt, and a pair of well-worn burgundy moccasins. On the wrist

of his left hand is a five-year-old plastic Swatch and the oval

metal-rimmed spectacles that he is wearing has its left side temple

bent-a fact unnoticed by the wearer until pointed out. Next day,

when he turns up for an evening photo shoot, he does so wearing

an 11-year-old tie, albeit a Hermes (you see it in the photo alongside).

"I haven't bought a suit in the last five years," he informs

the writer, not as a matter of pride, but fact.

That's one more thing global investors must

love about Ashish Dhawan, the 35-year-old Senior Managing Director

of ChrysCapital, and who calls Suite 101 in Oberoi his headquarters.

Five years ago, he and his class mate at the Harvard Business School,

Raj Kondur, gave up lucrative Wall Street jobs to launch an India-specific

fund under ChrysCapital (formerly Chrysalis Capital), to invest

in start-ups. Since then, Dhawan has raised, in two rounds, $200

million in funds from investors around the world, and on June 11

closed another, vastly bigger fund of $220 million (a greenshoe

option included, it will eventually close at $250 million in July).

That means Dhawan, the elder of two sons of a reasonably well off

but retired corporate executive, is the keeper of $450 million of

money from global investors, including the Harvard Foundation, Digital

Century (a hedge fund), HSBC and Microsoft, among others. Says a

Delhi-based private equity investor, who is currently doing the

rounds of international investor circuit to raise a fund of his

own: "For American investors (investing in private equity funds),

India starts and ends with Ashish Dhawan."

|

THE MAN AND THE INVESTOR

|

| First

and foremost, Ashish Dhawan is a family man. He came back to

India to get married to an Indian girl because he believed that

was the right thing to do in the long run. He moved headquarters

from Mumbai to Delhi and took up a suite in Oberoi because he

wanted to be close to his family. Currently, he lives with his

parents in their home in Delhi's Jor Bagh, but will be moving

out to his own nearby that he bought recently. Last week of

May, when he went to a fortnight-long vacation in China, he

not only took his wife and two children, but also his parents.

He's doesn't lead a page-three life, preferring quiet evenings

with his family and, occasionally, a few select friends. A social

drinker, he gave up red meat and turned to seafood after he

went down with typhoid last year. Although he doesn't get to

work out much, he likes to go skiing and scuba diving, which

in India isn't all that often. As an investor, Dhawan believes

in investing in a handful of industries where India has a chance

of succeeding globally. "I hate commodity investments,"

he says when asked if he would invested in steel or cement.

He also believes in letting the professionals in his investee

companies run the show. Says Raman Roy of Wipro Spectramind:

"He knows when to push and when to back off." |

| THE ESSENTIAL DHAWAN |

BORN:

March 11, 1969; Delhi BORN:

March 11, 1969; Delhi

EDUCATION: St. Xaviers Collegiate

School, Kolkata; BS in applied mathematics and economics, Yale

University; MBA, Harvard Business School

WORK EX: Wasserstein Perella,

July 1992-December 1993; McCown De Leeuw & Co., January

1994-June 1995; GP Investments (Brazil), Summer 1996; Goldman

Sachs, July 1997- March 1999

RECENT ACQUISITION: A house on

Delhi's tony Amrita Shergill Marg

LIFE'S GOAL: To build world-class

companies in India |

No doubt, he's exaggerating for effect, but

only a little. For, what Dhawan has managed to achieve in the private

equity business is the near impossible. In an era when venture funds

(the difference between private equity and venture funds is that

while the latter invest in start-ups, the former fund listed or

unlisted companies that already have sizeable revenues) were dominated

by large financial institutions, Dhawan & Co. jumped in as fresh-faced

kids with a naive conviction that they could a) get savvy investors

to put millions of dollars behind them, b) sell them the India story

(back in 1998-99 doing so was harder still), and c) actually make

investments that would pay off. And incredibly, they've been right

on all three counts. Says Prakash Karnik, an industry veteran: "In

many ways, Ashish is a pioneer. He changed the rules of the game.

For the first time in India, it was an individual, and not an institution,

launching a venture fund."

For that reason alone, Dhawan-not necessarily

the smartest of them all-is both the pride and envy of the industry.

In less than five years, ChrysCapital, the first half of its name

derived from Dhawan's school fest, has managed to return a 31 per

cent IRR (annualised) for its Fund One, and make two highly profitable

exits. One was the sale of Spectramind, a BPO, to Wipro, which fetched

the firm $60 million and the other was the sale of half its stake

in Jerry Rao's Mphasis to various institutions for $13 million.

That was approximately the amount ChrysCapital had invested in it,

and interestingly enough the other half of its stake is worth $30

million at current market valuation. The second fund, where investment

has been made in companies like IVRCL and Yes Bank, is said to be

running an IRR of 48 per cent, but even Dhawan admits that it will

be impossible to maintain that when it's time to pay back to investors

in 2006 or 2007. Still, depending on its exits, ChrysCapital should

be one of the top performers in the secretive business of private

equity. Says George E. McCown, Co-founder and Managing Director,

McCown De Leeuw & Co. (MDC), a Menlo Park (California)-based

private equity fund with $1.2 billion under management, and who

gave Dhawan and Kondur part of the seed capital to launch ChrysCap:

"They are probably among the top firms (in terms of returns)

of that vintage." Possibly as a reward, the otherwise thrifty

Dhawan has bought himself a house (the grapevine has it, for Rs

11 crore) on Delhi's upscale Amrita Shergill Marg, not far from

where Bharti Tele-Ventures' Chairman Sunil Mittal lives in an even

bigger and more expensive house.

|

DHAWAN'S A-TEAM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

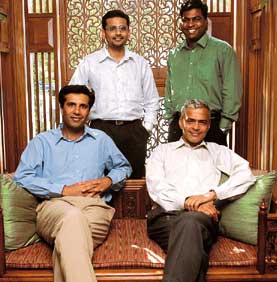

| A winning combo: (Anti-clockwise

from left) Brahmal Vasudevan, Adarsh Sarma, Kunal Shroff, Gulpreet

Kohli; (centre, anti-clockwise) Ashish Dhawan, Ravi Bahl, Ashley

Menezes and Sanjay Kukreja |

| Brahmal

Vasudevan: A Sri Lankan Tamil who grew up in Malaysia

and Britain, Brahmal went to Harvard with Dhawan and Kondur

and has worked with BCG and BAT. Currently, he's a Managing

Director in charge of US operations.

Adarsh Sarma: A little over

three years old at ChrysCap, Sarma has previously worked with

Radiowave (a media and technology company funded by Warburg

Pincus, Intel, and Motorola), McCown De Leeuw, and Merrill

Lynch. He has an MBA from Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Sanjay Kukreja: An economics

graduate, he's done more than four years at ChrysCapital.

He joined the firm fresh out of IIM Bangalore.

Gulpreet Kohli: He worked

with GE's BPO business before joining ChrysCapital in May

2000. Kohli has an MBA from Clark University.

Kunal Shroff: He was hired

even before ChrysCapital formally launched its fund in India.

Kunal previously worked with Chilton Investment Company, a

$2-billion hedge fund. At ChrysCap, Kunal, a graduate in computer

science from Cornell University, focuses on tech investments.

Ashley Menezes: A chartered

accountant by education, Menezes came to ChrysCapital three

years ago from KPMG, where he worked in the IT and US GAAP

practices.

Ravi Bahl: The oldest of the

lot, Bahl, a Managing Director, joined three years ago and

has worked with Citibank and eFunds, a transaction processing

company. A graduate of IIM Calcutta, Bahl came on board soon

after Kondur left.

|

Salesman #1

Talk to private equity players in India and

they'll tell you that Dhawan's networking and money-raising skills

are "light years ahead (that) of others". But the idea

of a venture fund like ChrysCapital may actually have been fathered

not by Dhawan, but by McCown. Here's how: About 10 years ago, when

Dhawan had just passed out of Yale with an undergraduate degree

in mathematics and economics and had taken up a job at McCown's

firm as an analyst, Dhawan's father (Anand) happened to visit California

and meet McCown. At that time, McCown was trying to raise a third

fund for MDC and Dhawan senior suggested that he tap business families

in India because recent liberalisation of the economy may have got

them interested in markets abroad. McCown, an Indophile, came with

his young Indian employee in tow, and went around meeting some of

the big business families. As it turned out, the Birlas and the

Tatas were more interested in investing in India than overseas.

That got McCown thinking and he was keen to open an India office

for his own firm. But Dhawan, only 25 years old back then, felt

that they should wait for a few more years. McCown agreed.

At Harvard, the idea planted by McCown took

shape when Dhawan and Kondur (besides class mate Sanjiv Bajaj of

Bajaj Auto) started working on a case study on India (apparently,

it is now taught at HBS). But instead of taking the plunge right

away, Dhawan and Kondur decided to take up Wall Street jobs-Dhawan

at Goldman Sachs as part of its $4-billion hedge fund business and

Kondur at Morgan Stanley, where he was part of the team managing

the $1-billion Princess Gate Fund, which invested in telecom and

it. Ironically, the defining moment came with Dhawan's (arranged)

marriage in July 1998. When he came to Delhi, he sensed that the

time was ripe for launching an India fund. Returning to the Big

Apple with his new bride, Dhawan-who until then shared a large apartment

with Kondur at SoHo in Manhattan-told his friend that he planned

to take the plunge. Was he interested in joining hands? Kondur was.

In the latter half of 1998, Kondur and Dhawan

(who by then had moved with his wife to a one-bedroom set up on

225, East 79th Street) started putting their business plan together.

Once they had their 15-page presentation finalised, they made a

pitch to McCown and Jeffrey C. Keil, Chairman of International Real

Returns, a private investment advisor. It helped that both McCown

and Keil were Harvard alumni, besides which McCown had been Dhawan's

employer just a few years earlier. McCown and Keil, along with some

of their partners, gave Dhawan and Kondur $500,000 in seed capital

to go out and raise money from other investors. They also promised

to invest $20 million, provided the energetic duo could get other

investors to first cough up $35 million at least.

|

A PARALLEL STORY

|

| Westbridge capital

partners, a $140-million fund, has a story similar to that of

ChrysCapital. Like Ashish Dhawan and Raj Kondur, WestBridge's

Sumir Chadha and K.P. Balaraj also graduated from the Harvard

Business School, and worked with Goldman Sachs. And like ChrysCapital,

WestBridge has managed to get some big investors interested

in India. In the latter's case, investors include Goldman Sachs,

Merrill Lynch, and Capital Z. But unlike ChryCapital, they haven't

managed any hi-profile exit yet, and neither do they have as

diversified a portfolio as ChrysCapital's. Their concentration

is on information technology and outsourced services (BPO),

with investments in companies like Strand Genomics, July Systems,

Emagia, Celetronix and ICICI OneSource. The last two-Celetron

is based in the US and ICICI OneSource in India-are set to go

public in the next 6-12 months. Once that happens, "our

performance will probably be at the top or very top of our VC

peer group globally", says Balaraj, who heads India operations

out of Bangalore. |

Over the next five months, Dhawan and Kondur

criss-crossed the US, flying cheap airlines and living out of inexpensive

hotels, and met dozens of potential investors. A few said a polite

no, but most, interestingly, liked their sheer energy and enthusiasm.

Among them were people like Henry M. Paulson Jr., Chairman and CEO

of Goldman Sachs, Rajat Gupta of McKinsey, Victor Menezes of Citigroup,

Gurcharan Das, formerly of P&G, besides companies like Microsoft.

Says Das: "In some ways, they reminded me of myself when I

was their age. They had this fire in their belly and a desire to

come back and do something for the nation." In the fall of

1999, they closed the fund at $63.8 million. Messrs Dhawan &

Kondur were in business.

Damned by the Dotcoms

When the two young investors (Dhawan had just

turned 30 and Kondur was only 28 then) moved into their 900-sq-ft

office in Mittal Chambers in Mumbai's business district of Nariman

Point, the dotcom frenzy in the US was already winding down. But

in India, Net babies were still mushrooming out of every nook and

cranny, and Dhawan-whose basic idea was to replicate America's dotcom

boom in India-refused to believe that it could die a sudden death,

which it did. So, in a matter of 90 days, Dhawan and Kondur mowed

through some 500 business plans and even visited 150 outfits. While

their average size of investment was small, they wagered on a string

of dotcoms with names as bizarre as Cheecoo and Planet Saffron (See

The Doomed Dotcommers). More than 40 per cent of the $64 million

went into such companies, and most of it had to be written off in

2001.

Around late 2000, when it became apparent that

dotcoms in India were doomed, Dhawan realised that they had a big

mess on their hands. Two things needed to be done: One, salvage

whatever little value was left in their dotcoms and, two, cobble

together a new fund if ChrysCapital were to have a tomorrow. Early

2001, Dhawan and Kondur hit the road again to raise some more money.

They travelled "like mad men" over six months "banging

a lot of new doors". A lot of the previous investors didn't

come on board, but luckily for them Harvard, which has a fund pool

of $20 billion, obliged this time round, and the duo finally managed

to raise $127 million. "It was a lifeline that had been thrown

to us and we were determined not to mess up this time," recalls

Dhawan.

|

THE CHANGING COLOURS OF PRIVATE EQUITY

|

|

When Ashish Dhawan and Raj Kondur

set up their own venture fund in 1999, they were one of the

first individuals to get into a business traditionally dominated

by large financial institutions in India. But in more mature

markets like the US, individual manager-led funds have always

been the norm. That trend is finally beginning to emerge in

India. So far this year, two private equity firms-CDC Capital

Partners and Baring Private Equity Partners India-have seen

their managers do a buy-out. In other words, instead of CDC

of UK raising and investing funds, it will be the new management

companies (Actis in the case of CDC and Rahul Bhasin, who

gets to retain the Baring name) that'll run the show. What's

forcing the trend? Investors, who want the fund managers,

and not their institutional employers, to make money. That's

swell for the managers, because apart from the 2 per cent

management fee that they get to keep from the overall size

of the fund to manage their expenses and pay salaries over

a five-year period, they stand to gain-in a typical situation-20

per cent of the profits as bonus, provided they deliver a

minimum return agreed to by investors. In the case of ChrysCapital,

if the third $250-million fund crosses such a "hurdle

rate" and assuming it returns 30 per cent, Dhawan and

his team will get 20 per cent of $75 million-or a cool $15

million.

|

In a move that surprised ChrysCapital's investors

too, Kondur quit-ostensibly to set up his own BPO, but actually

because the partners fell out-and Dhawan had to rope in more experienced

managers like Ravi Bahl, who joined in the middle of 2001. By then

ChrysCapital also refocussed its own strategy and decided to be

a generalist rather than a specialist fund, to do "growth capital"

(industry jargon for funding companies seeking aggressive growth),

to invest in start-ups only in industries that the team understood

thoroughly, and to set up an office in the US not just for fund

raising, but also investment. "We realised that to be successful,

we had to do fewer things and do them better," says Brahmal

Vasudevan, Dhawan's Harvard batchmate and head of ChrysCapital's

US operations.

The investments that followed were in stark

contrast to the, well, irrational exuberance of Fund One. BPO, it

services and financial services became the core of the second fund,

although it has an infrastructure company, Hyderabad-based IVRCL,

in the portfolio too (See The Comeback Portfolio). In each of these

companies, ChrysCapital has picked between 8 per cent (like in Yes

Bank and TechTeam) and as high as 80 per cent (in Global Vantedge).

Going by the average performance of the portfolio, the second fund

is clipping at an annual IRR of 48 per cent, but Dhawan points out

that the rate will be hard to hold on to. Yet, it's unlikely that

it will perform any worse than the first fund. Says Raman Roy, Chairman

and Managing Director, Wipro Spectramind: "Ashish is one of

the smartest guys around, he understands things very quickly."

Smart Fund Raiser, Smarter Investor?

Few in the private equity business will dispute

Dhawan's extraordinary fund-raising ability. But ask them if he's

as brilliant an investor and they'll demur. First of all, they point

out-and to be fair, Dhawan readily admits as much-ChrysCapital is

not about him alone. There are several smart managers (See Dhawan's

A-Team) who work with him. In fact, one of his former colleagues

says that much of ChrysCapital's dotcom fiasco happened because

of Dhawan's infatuation with the phenomenon. Besides, Kondur, and

not Dhawan, may have been the driver of ChrysCapital's first-ever

and the most famous and life-saving deal: the investment in Spectramind.

When ChrysCapital started talking to Raman Roy, he was already negotiating

with at least six other venture funds and the man who spent the

most time trying to woo Roy (once, an entire day on October 9, 1999)

was Kondur, not Dhawan. Even Spectramind's deal with Wipro happened

not because of Dhawan (Kondur was out by then), but because of Azim

Premji, who personally visited Spectramind's Okhla facility before

investing $10 million in 2001. The final landmark deal where Wipro

bought out ChrysCapital's stake for $60 million about a year later

also happened because of Premji stepping in-especially when it came

to buying the management's part of the stake. Says Suresh Senapaty,

CFO, Wipro: "Basically, (Premji) told us to ensure that the

management felt like a winner in this deal."

|

KEY EXITS AT CHRYSCAPITAL

Not companies, but people.

|

Raj

Kondur Raj

Kondur

Co-founder and Dhawan's Harvard buddy and flat mate, Kondur

ostensibly left to launch his own BPO outfit. In reality, Dhawan,

who even then owned the majority stake in ChrysCapital, may

have forced his exit.

Shujaat Khan

He was another Managing Director at ChrysCapital. When BT

last heard of him, he was looking for a job.

Luis

Miranda Luis

Miranda

He was a Managing Director at ChrysCapital, but fell out with

Dhawan. An MBA from Chicago, Miranda now heads IDFC Asset

Management Co.

|

Another criticism about Dhawan you are likely

to encounter in the business is that he's figured out a great way

to avoid lemons-"he simply piggy-backs on deals of other private

equity investors," one of his competitors told BT. As evidence

they point to UTI Bank, where CDC Capital Partners got in first,

Mphasis, where Baring Private Equity Partners India made a bigger

and bolder bet by buying an ailing BFL Software and then merging

it with Jerry Rao-promoted Mphasis, or IVRCL and Yes Bank, where

CVC International made the first move.

But, then, you don't get into Harvard and graduate

with flying colours if you don't have a damn good head on your shoulders.

To Dhawan's credit, he did spot the BPO wave much ahead of its coming

and he also knew which horse to back. He was also smart enough,

even as a 29-year-old, to turn down McCown's suggestion to bring

the first fund as a McCown De Leeuw venture. As McCown told BT,

Dhawan felt that an indigenous fund would better appeal to Indian

entrepreneurs. Says Giri Devanur, CEO of Ivega, an investee company

recently sold to The Chatterjee Group: "Ashish is a brilliant

individual. He is a trend spotter and is able to latch on to new

things very quickly." Devanur speaks from experience. In early

2000, he ignored Dhawan's advice to move into the BPO space and

suffered for it.

Not just that. Dhawan, who was born in Delhi

but went to school in Kolkata's St. Xaviers, can really push himself.

E. Sudhir Reddy, 43, Vice Chairman and Managing Director of IVRCL,

recalls his first meeting with Dhawan last November. It was supposed

to be a breakfast meeting but Dhawan ended up spending close to

eight hours at their office, chatting up everybody from the engineer

to the draftsman in his bid to understand IVRCL's business. Past

month, when Dhawan went to China on a vacation with his wife, two

kids, and parents, he was regularly working his mobile phone. Says

Ajay Relan, Managing Director of CVC International, a good friend

and neighbour: "He's incredible. He was sending me four-to-five

text messages a day and also calling up because we were trying to

get a deal done."

Dhawan, who likes an occasional evening walk

in Delhi's Lodhi Gardens with friend, mentor and investor Das, can

also display tremendous amount of courage if he's convinced about

an investment. For example, soon after he invested in Mphasis, paying

Rs 350 a share when the prevailing market price was Rs 230, the

stock plunged to Rs 60. But Dhawan held on, convinced that Mphasis

was a good bet in the long term. Says Jerry Rao, Chairman and CEO,

Mphasis: "It must have taken a lot of courage and foresight

to invest in us back then." His stand was vindicated. Today,

the stock quotes at Rs 245, post a 1:1 bonus, and ChrysCapital still

has half its original investment in the company that is worth another

$30 million. Says McCown: "Every year we have three or four

undergraduate analysts at the firm who stand out. But Ashish is

simply the best we ever had."

But as some super achievers can be, Dhawan

is impatient and not as good a people manager as some expect him

to be. For instance, his former colleagues are pretty bitter about

their experience at ChrysCapital. A rival private equity investor

complains how Dhawan once hijacked a done deal simply by offering

a higher valuation. Another one-time friend, who claims to have

acted as Dhawan's sounding board when the fund was being set up,

says that when it was his turn to ask Dhawan for help, he didn't

give him the time of day. Dhawan's defence: "I am not perfect."

Not that Dhawan can't be inspiring when he wants to. Rao of Mphasis

recalls the "brilliant speech" that Dhawan delivered soon

after he made the investment. It was so good that it worked like

a "shot in the arm". Dhawan also doesn't interfere in

the day-to-day operations of his investee companies. "If we

have to run a company, it means we've messed up," he says.

With his third fund, Dhawan wants to do more

of the same thing: invest in promising companies in a wide variety

of industries. He is currently looking at a few deals, one of which

is a heavy engineering company. "I want ChrysCapital to be

a premier investment firm that is ahead of the curve and is associated

with building a few world-class companies from India. With the third

fund, I have that platform," he says. Dozens of investors around

the world seem to think that he does. Now, Dhawan only has to deliver.

-additional reporting by Priya

Srinivasan in Mumbai, Venkatesha Babu in Bangalore, and

E. Kumar Sharma in Hyderabad

|