|

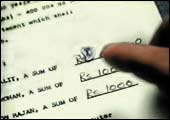

| This recent advertisement for a sealant didn't

end all that well for the unscrupulous heir. But reality is

very different; that's why you should read this article on wills

and will-making |

There's

something the Indian psyche finds distasteful about the practice

of writing wills. ''I am not going to die tomorrow,'' snaps Siddharth

Shriram, Chairman of SIEL, when asked if he had made one. It's the

association with death that draws reactions such as this but a will,

says Max New York Life CEO Anuroop 'Tony' Singh, is pretty much

like ''life insurance; you don't think of it in the normal course

of life''. The business of insurance, courtesy competition, has

grown-by 60-65 per cent in the past year by some estimates as compared

to 20-22 per cent the year before-and thanks to changing value systems

(Shriram, after all, is a businessman from the old school) more

people are writing wills.

Wills weren't all that imperative in a milieu

where the extended joint family was the norm. ''Family property

is usually locked (in) by laws and the power of disposition is limited,''

explains Zubin Morris, a partner at law firm Little & Co, which

helped the late Aditya Birla draft his will. ''So, members of joint

families often don't bother to write wills.'' Joint families, though,

are on the way out, and an increasing awareness of legal issues

is driving more people to write (and register) their wills. ''People

take the writing of wills more seriously now,'' says Dr Abhishek

M. Singhvi, the late Madhavrao Scindia's counsel during the contesting

of Rajmata Scindia's will. ''They even videotape themselves doing

so (writing their wills).''

It isn't hard to make a will out in India.

All one needs to do is put down everything on paper (type it, preferably

so that courts may be spared the trouble of deciphering handwriting),

find two witnesses-a doctor as one would be ideal; he or she can

attest that the testator (as the person making the will is called)

is of sound mind-and roll. Registering a will isn't mandatory although

it does assure the document's 'legal sanctity'.

Registration is no insurance against the will

being contested, something that happens to most in India, ''especially

because property is at stake,'' says Rajiv Dhavan, a Delhi-based

lawyer. The grounds on which a will can be contested cover pretty

much everything, from questions on its authenticity to issues relating

to the mental health of the testator. And if the will favours someone

outside the immediate family, they can always contest it, and things

could drag on and on...The childless owner of Manmohan building

in North Delhi's Yusuf Sarai-one of those typical Delhi buildings

with rabbit warrens that pretend to be offices-willed it to a university.

His nephews and tenants convinced another university that he had

wanted to bequeath the property to it. Today, 30 years after his

death, the universities are still battling it out in court. ''Our

legal system encourages litigation as opposed to settlement,'' rues

Dhavan.

|

Will-making 101

|

|

»

If there is anything unusual in your

will, make sure you clearly explain why.

»

Ensure that someone knows where

your will is so that no fake wills crop up after your demise.

»

Keep your will updated at all times

and remember-it's the last one that counts.

»

It is good idea to have a doctor

as a witness so no one can say you wrote it after losing your

marbles.

»

Don't be lazy-get your will registered

as soon as possible. At the end of the day it does count for

something.

|

If contests are one part of the problem with

wills, inadequate drafting is another. In one instance, a prominent

Delhi-based businessman bequeathed his house to his widowed daughter-in-law.

A subsequent will left the property to his daughters and asked the

daughter-in-law to vacate the house by a certain date, but gave

her a portion of the proceeds of the sale of the house. Only, the

will didn't say anything about how and when the house had to be

sold.

A will, for those of you who don't know this

already, is revocable and can be superseded by another will. The

last will is usually the valid one. A much talked about case is

that of Rajmata Vijayaraje Scindia's will. A handwritten, 11-page

will, dated September 20, 1985, was produced after her death by

her Secretary, Sardar Angre. This will disowned her son Madhavrao

Scindia. Law firm Crawford Bayley and Company said it possessed

a later will in which the Rajmata had named her three daughters

as executors, but would not disclose its contents. The 1999 will

only further complicated an ongoing battle, one that the New York

Times observed would almost certainly have, ''an even lengthier

afterlife in the leisurely Indian legal system.''

So, what's all this talk of missed (or embattled)

inheritances doing in the personal finance section of the magazine?

Only this: everyone-no matter if your worldly possessions comprise

dud stocks, a house in Cochin that hasn't seen any appreciation

in value in 10 years, and a 1988 Maruti 800-needs a will.

That's one. Two, be very clear in your mind

as to what you wish to do with your assets. List movable and immovable

assets separately. And remember to include a rationale for seemingly

inexplicable decisions. ''If you want to leave your property to

one person and not the other, you should include a reason; otherwise

the will can be contested,'' says Avantika Keswani, a Delhi-based

lawyer. Also remember to dot your is and cross your TS lest poor

drafting skills undermine your intent.

Do you need a will? Actually, everyone does;

especially people with a family. Indeed, as some recent cases show,

if you don't make your will, someone else could (this actually happened

to an Indian settled in Malaysia; someone who knew about his holdings

in India forged a will and got it registered). That's why registrars

have increasingly moved to the practice of attaching the testator's

photograph to the will.

The growing relevance of wills (or drafting

wills), says Max New York Life's Singh, is actually a business opportunity.

''Alas, no one has marketed wills as a product; what a great idea.''

We agree.

|