|

|

|

|

|

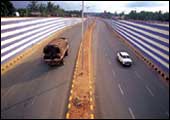

| From top: The seat of power—the

Vidhan soudha; a booming city; the Outer Ring Road; a city on

the move, and a bustling foodcourt |

On

the day in July his company declares its not-so-flattering results

for the April-June quarter Wipro Ltd. Chairman Azim Premji, a patrician

57-year-old with an unruly white mane, decides he has had enough.

Wipro's corporate office is in Sarjapur, a Bangalore borough that

has stayed off the radar of city departments, athough a proposed

it corridor linking Electronics City in the south of the city to

Whitefield in the north should change that. The road to Wipro's

office is bad, accidents are commonplace, and on this particular

day the telephones are down-reason enough for the usually placid

Premji to launch a broadside at the state government.

Bangalore, a city of six million that has emerged

the hub of knowledge-businesses in India, is a mess. Brown-outs

are a way of life, parts of the city suffer from water shortage,

and peak-time commuting is torturous, if not downright hazardous.

Delhi has better roads, Mumbai, a more reliable power-supply, and

Chennai has made some faltering progress towards installing a city-wide

Mass Rapid Transit System (an elevated railway), a process that

is stuck somewhere in the government-works in Bangalore.

A few hours before Premji's offensive, Karnataka

Chief Minister S.M. Krishna meets with Nandan Nilekani, the CEO

of the city's best-known company, Infosys Technologies, and Chairman

of the Bangalore Agenda Task Force, an entity vested with the responsibility

of working with city departments to upgrade Bangalore. Also present

are bureaucrats, including the Commissioner of Bangalore Development

Authority, Jayakar Jerome.

Jerome is a 56-year-old born-again Christian

whose zeal extends into his job. When he took over, the government

was mulling the closure of BDA, which had allotted all of 3,400

plots in the preceding decade.

In his three-and-a-half years in office, Jerome

has recovered BDA land valued at Rs 400 crore that had been encroached

upon, allotted 40,000 plots, and raised Rs 100 crore through an

issue of debt that was rated LAA+ by ICRA. And BDA, although it

isn't required to, uses its money to build roads and overpasses.

The most ambitious of such efforts is a 66-kilometre stretch that

marked the completion of Bangalore's much-awaited Outer Ring Road,

a road the National Highways Authority of India now wants to buy

off BDA.

Apart from making several enemies-he has received

death threats from the local land mafia-Jerome has turned BDA into

a cash-rich organisation and become the visible symbol of the Chief

Minister's reformist credentials.

One of the items on the agenda for this morning's

meeting is the restoration of Lalbagh, a city park built in the

18th century by Hyder Ali that has since fallen into some level

of disrepair. Till as recently as the 1980s, Lalbagh, with its rose

garden and a glasshouse modeled after Kew Garden's Palm House, was

a tourist attraction. The park covers 260 acres in Bangalore's older

quarter and Krishna would like nothing better than to see it regain

its lost glory. He thinks BDA is just the organisation to effect

this. The catch? The park is administered by another city department

that, at this meeting, offers to do whatever is required if BDA

bankrolls it. Jerome is having none of that. "I am not giving

one rupee of BDA's hard-earned money to anyone," he says. The

Chief Minister indicates that he would like BDA to do the job; the

other department falls in line.

| Bangalore's Success-Ingredient #1: The complete

backing of the political organisation |

At 7.30 a.m., an hour before the Chief Minister's

meeting begins, 600 volunteers-professionals, retirees, salarymen,

homemakers-leave their homes and head for designated garbage collection

areas to supervise the process, part of the Swachcha Bangalore programme

launched by BATF and Bangalore Mahanagere Palike, the city corporation.

Wipro is among the first lot of companies to

declare its results for the April-June quarter, but BMP's accounts

for the same period are ready too, courtesy a Fund Based Accounting

System (EFF bass, or f-bas) designed by Ramesh Ramanathan, previously

Managing Director and European Head, Derivatives Marketing, Citibank

N.A., and now, Member, BATF and Campaign-Co-ordinator, Janaagraha,

a citizen's organisation with a membership of 250,000. "We

are the only municipal body in the country that declares quarterly

results," says bmp Commissioner Sreenivasa Murthy.

One of the city's colleges is closed this Friday.

Its students, under the aegis of Janaagraha, have volunteered to

map the city, inch-by-painstaking-inch-information that will be

ported on to satellite maps of the city provided by the National

Remote Sensing Agency to create the basis for a 10-year Comprehensive

Development Plan on which Janaagraha and BDA are collaborating.

Ramesh's wife Swati Ramanathan, a trained architect and urban planner,

believes the CDP, apart from helping city agencies administer Bangalore

better, will help citizens define and create their kind of city.

|

| From left: Nandan Nilekani, CEO Infosys,

Jayakar Jerome (seated), Commissioner, BDA and S.M. Krishna,

Chief Minister, Karnataka |

Elsewhere in the city, Harish Bijoor, a former

beverage and telecom exec who now runs an eponymous consulting firm,

is mapping out the area he and his army of 22 volunteers will clean

this weekend.

Something is happening in Bangalore and the

world is beginning to take note. New Delhi Municipal Corporation

is working on an EFF-bas and the Comptroller and Auditor General's

recent accounting guidelines for urban local bodies borrow extensively

from the bmp model. BATF Member V. Ravichandar, Managing Director,

Feedback Marketing Services, an industrial market research agency,

is off to Tiruchirapalli, a city in Tamil Nadu, next month to brief

its corporation on the Bangalore experience-a presentation he has

already made to Mumbai, Pune, Nasik, Trivandrum and a few other

cities. Delhi unsuccessfully tried to woo BDA's Jerome to head Delhi

Development Authority. And Bombay First, a joint venture of some

of Mumbai's best-known citizens and bureaucrats that was founded

in 1995, has woken up to the achievements of BATF and is desperately

playing catch-up-these days, the buzz in Mumbai is about a Bombay

First-McKinsey report on transforming the city into a "world

class" one by 2013.

Disparate events such as chip major Intel's

decision to invest in a large development centre in the city, rising

real estate prices, and the high occupancy in the city's five-star

hotels, then, may have less to do with the cycles such things seem

to follow, and more to do with Bangalore's revival. Yesterday's

Silicon Alley may well be India's most happening city tomorrow.

If it gets there it will be because of an unique partnership of

the government, the private sector, and the public, a partnership

that perhaps belongs more in an evolved Scandinavian country (anyone

seen their human development indices?) than in the capital of India's

eighth largest state.

| Bangalore's Success-Ingredient #2: Private

sector participation in the business of governance |

The beginnings of Bangalore's renaissance can

be traced to Hyderabad, and to a hoary eatery on Bangalore's St

Mark's Road. It was late 1999. Krishna, a lawyer by training who

looks more like a professor than a politician, had just been elected

Chief Minister. And he was angry. Some astute jockeying by Andhra

Pradesh Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu had seen the McKinsey-promoted

Indian School of Business decide to base itself in Hyderabad. "On

the basis of all the recognised parameters, I thought it should

have been Bangalore," he says. "So, when I took over,

I wanted to send out a message that Bangalore would not remain the

same; that it would regain its former glory." Around the same

time, two of Krishna's close aides met at Koshy's, a Bangalore institution

that has aged well-it still serves a mean vindaloo-and decided that

the Chief Minister could do worse than form a committee and appoint

Nandan Nilekani to head it.

The committee was the Bangalore Agenda Task

Force and it was one of the 13 task forces-most headed by CEOs-instituted

by the Krishna Government. The other task forces presented their

reports and faded out of existence. "We were very sure we weren't

going to present a report," recollects Kalpana Kar, a former

Tata Administrative Services Executive and Member, BATF. "The

city had some 76 of them." Instead, says, Kar, the task force

decided to work with the various local government bodies responsible

for managing the city. Kar herself works with bmp. And BATF's resident

evangelist Ravichandar works with BDA. "We weren't going to

stand outside the system and badmouth it," says Ravichandar,

referring to preferred activist strategy. "We were going to

change it from the inside."

HYDERABAD BLUES

How Cyberabad fares |

|

It's

no secret in Delhi's power circles that Andhra Pradesh Chief

Minister Nara Chandrababu Naidu, a key ally of the BJP, usually

gets what he wants. Naidu was the first Indian Chief Minister

to see himself as a CEO; unfortunately, he doesn't seem to

have been able to build an organisation, or effect structural

and systemic reforms. Hyderabad, consequently, has suffered.

Still, Naidu is trying his best to ensure that Hyderabad steals

a march over Bangalore: he is lobbying the government to move

to an open sky policy and make Hyderabad a transit point between

Europe and China; he plans to make the planned Hyderabad international

airport one of Asia's biggest and most modern; and he is already

pitching Hyderabad as the pharmaceutical, biotech, and health

services capital of India. All very creditable, but equally

individual-driven, and very very "top-down" as one

city planner puts it. The participative nature of Bangalore's

renaissance could well give that city an edge. It's

no secret in Delhi's power circles that Andhra Pradesh Chief

Minister Nara Chandrababu Naidu, a key ally of the BJP, usually

gets what he wants. Naidu was the first Indian Chief Minister

to see himself as a CEO; unfortunately, he doesn't seem to

have been able to build an organisation, or effect structural

and systemic reforms. Hyderabad, consequently, has suffered.

Still, Naidu is trying his best to ensure that Hyderabad steals

a march over Bangalore: he is lobbying the government to move

to an open sky policy and make Hyderabad a transit point between

Europe and China; he plans to make the planned Hyderabad international

airport one of Asia's biggest and most modern; and he is already

pitching Hyderabad as the pharmaceutical, biotech, and health

services capital of India. All very creditable, but equally

individual-driven, and very very "top-down" as one

city planner puts it. The participative nature of Bangalore's

renaissance could well give that city an edge.

|

The Ramanathans were part of that change. Five

years ago, they decided to return to India from London. Ramesh wanted

to work in the area of urban poverty, and runs a Bangalore-based

micro finance organisation Sanghamitra. Along the way he became

interested in government finances.

It's easy to visualise someone like Ramanathan

in Citi's Type-A environment: he speaks rapidly, in short staccato

sentences, and uses the language of business. "It's amazing

that no government has a double-entry book keeping system,"

he says. And so, he put his energies to understanding best practices

in government accounting.

The accepted double-entry system of bookkeeping

originated in Italy in the 14th century, although it wasn't until

1494 that a monk by the name of Luca Pacioli wrote about it in detail.

The founding of The East India Company-it introduced the concepts

of invested capital and dividends-accelerated the spread of accounting.

Government accounting, in contrast, is a recent phenomenon.

It was only in the early 1990s that New Zealand

moved to an accrual accounting system. Other countries followed

and the US Governmental Accounting Standards Board collated best

practices and came up with a prescribed set of standards.

| Bangalore's Success-Ingredient #3: Involvement

of the city's citizens in governance |

In his mind, Ramanathan is very clear that accounting

is at the core of all governmental reform. "Everything has

to start from accounts," he says. "That is the biggest

difference between the government and the private sector."

Under the aegis of the Public Affairs Centre, a non-governmental

organisation founded by Samuel Paul, a quiet-spoken academic who

has served as Director, Indian Institute Management, Ahmedabad,

Ramanathan was wrestling with implementing an EFF-bas for Tumkur,

a small town in southern Karnataka-he was making no great progress-when

he was inducted into BATF in early 2000. He saw his chance.

With money from Nandan and Rohini Nilekani's

Aadhar Trust (the couple has thus far put in around Rs 4.75 crore

of its personal wealth into BATF initiatives), Ramanathan went out

and hired 22 commerce graduates; bmp gave him use of a room in its

HQ. All told, the team spent around 300,000 man-hours tracking the

paper and money trail at bmp, devising a nomenclature for various

expense heads, and assigning codes to every piece of developmental

work being carried out by the corporation. The process took 14 months,

but by April 2001, bmp had an EFF-bas in place.

City corporations aren't the most reform-minded

organisations. Still, with the inducement of some Rs 361 crore from

the state government if it met some conditions-one of these required

the corporation to move to a modern accounting system and the two

bodies signed a memorandum of understanding to this effect in July

2001-bmp agreed to implement its F-bas.

DELHI DIARY

Capital concerns remain |

|

In 1999, soon after the congress

government took over in Delhi, Chief Minister Sheila Dixit

launched a programme branded Bhagidari targeted at increasing

the involvement of resident welfare associations (RWAs) and

NGOs in local governance. By including 'Commitment to Bhagidari'

as a head in the appraisal of bureaucrats, Dixit managed to

get the administration to heel. However, although Bhagidari

boasts some success stories in solid waste management and

rainwater harvesting, the scheme is not a runaway success.

Says Arun Mishra, Deputy Secretary, Delhi Government, the

man in charge of Bhagidari, "Right now, we are not focusing

on results, but on sensitising the populace." For how

long?

|

F-bas isn't the only thing of note in the Bangalore

of the future, but it is representative of the city's approach-scientific,

scalable, and result-oriented. Similar initiatives abound. There's

the Self Assessment Scheme (SAS) for property tax that has doubled

receipts to around Rs 200 crore in a mere four years. There's the

Nirmala programme (funded by Infosys co-founder N.R. Narayana Murthy's

wife Sudha Murthy who wrote a cheque of Rs 8 crore) that has built

23 public toilets across the city; 100 more are in the offing. There's

the Police Department's unique Central Area Traffic Plan, built

around a clutch of one-way-only roads, and designed with the assistance

of urban planners W.S. Atkins. And companies-Biocon, Bharti, Infosys,

Aditi-have been in the thick of the action, offering money and expertise.

"There's no question that you need (radical) tools and systems

for better governance," says Nilekani. "These get amplified

with (our) participation." And without these, he adds, one

cannot expect the system to operate the way Infosys does.

K. Jairaj isn't your everyday bureaucrat. The Principal Secretary

to the Chief Minister has studied law, economics and public policy

at the Universities of Delhi and Bangalore in India, and at Harvard

and Princeton. He has also served as the President of the All India

Management Association, the only bureaucrat to have done so ever.

So, when Jairaj stops three-quarters of the way through a complex

sentence involving What Really Works, an article by Nitin Nohria

in a recent issue of Harvard Business Review, Infosys Chairman N.R.

Narayana Murthy's oft-quoted gem about "excellence in execution",

and his own belief of how there is no difference between the public

and private domains, and launches into some fulsome praise of Krishna,

it is hard to attribute that to sycophancy.

It is even harder to do so when Nilekani, the

CEO of one of India's most transparent companies, says: "The

Chief Minister believes that there can be new solutions-an attribute

unusual in an Indian politician.''

| Bangalore's Success-Ingredient #4: Systemic

reform |

Bangalore's love for its present Chief Minister

probably has its roots in Karnataka's misfortune of being administered

by some of the country's worst politicians for the preceding decade

and a half.

In a country where 70 per cent of the population

lives in rural areas, it is suicidal for a politician to be seen

to be addressing urban issues. Krishna's critics like to point out

that the Chief Minister doesn't seem to be worried about parts of

the state other than Bangalore. "I can't create a parallel

Bangalore (in some other part of the state)," snaps the Chief

Minister. "There are well-laid roads leading to all towns;

all villages have access to potable drinking water; and we have

made tremendous progress in the areas of health and housing."

He pauses for a minute and probably realises that he hasn't been

harsh enough on his detractors. "People who say this,"

he says, carefully choosing his words, "have not stepped out

of Bangalore."

Still, with elections due in November 2004,

the government is taking the Bangalore-model of development to 30

cities and towns across Karnataka.

Being a Congress Chief Minister in a country

governed by the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance isn't easy.

Krishna has, time and again, pulled out numbers to show how Andhra

Pradesh, governed by the Telugu Desam Party, a BJP-ally, has benefited

from the centre's munificence. Then there's the muddle of party

politics. Early this year, when a member of Krishna's Cabinet made

some unflattering observations about Congress President Sonia Gandhi,

Bangalore (well, part of it) feared that the CM's head would roll

along with the minister's.

Krishna himself promises to "redouble

the pace of reforms," because they "have a direct bearing

on quality of life", but Bangalore needn't worry. It has systems

such as EFF-bas in place and because these can always been contravened,

it has that something else, a secret weapon (weapons, actually)

of sorts that has the potential to keep things ticking, Krishna

or no Krishna, Congress or no Congress.

BOMBAY SECOND

Why Bangalore prevails |

|

In

1995, some of Mumbai's corporate community, including Keshub

Mahindra, Chairman, Mahindra & Mahindra, Deepak Parekh,

Chairman, HDFC Ltd, and S.M. Datta, Chairman, Castrol India

Ltd, came together to help reinvent Mumbai. Along with some

government officials, they formed an organisation called Bombay

First. Today, eight years later, Bombay First is waiting for

the final results of a McKinsey study on transforming Mumbai

into "a world class metro" by 2013. The firm's recommendations

are expected to show how the city's Gross City Domestic Produce

can grow at between 8 per cent and 10 per cent. "We are

looking at finance, entertainment, and retail as some of the

key drivers for growth," says Bombay First CEO S.S. Bhandare.

"This is potentially a world class city," agrees

an investment banker. "Whatever I have heard about the

McKinsey plan sounds good; they talk a lot about mass transport

and affordable housing." There's no denying that housing

and transport are Mumbai's biggest challenges, but Bhandare

and the banker are among the minority that thinks the report

will make a difference. "Let's face it, the malaise is

a political one," says Gerson DaCunha, the first CEO

of Bombay First. "We have always been saddled with criminal

administrators with narrow self-interests." Darryl D'Monte,

a journalist and environmentalist who is involved in Bombay

First, has the last word. When asked whether he can name a

single effort involving citizens, the government, and corporates,

his response is a crisp, "no". That's one reason

Bangalore, more than Mumbai, is better placed to be India's

city of the future. In

1995, some of Mumbai's corporate community, including Keshub

Mahindra, Chairman, Mahindra & Mahindra, Deepak Parekh,

Chairman, HDFC Ltd, and S.M. Datta, Chairman, Castrol India

Ltd, came together to help reinvent Mumbai. Along with some

government officials, they formed an organisation called Bombay

First. Today, eight years later, Bombay First is waiting for

the final results of a McKinsey study on transforming Mumbai

into "a world class metro" by 2013. The firm's recommendations

are expected to show how the city's Gross City Domestic Produce

can grow at between 8 per cent and 10 per cent. "We are

looking at finance, entertainment, and retail as some of the

key drivers for growth," says Bombay First CEO S.S. Bhandare.

"This is potentially a world class city," agrees

an investment banker. "Whatever I have heard about the

McKinsey plan sounds good; they talk a lot about mass transport

and affordable housing." There's no denying that housing

and transport are Mumbai's biggest challenges, but Bhandare

and the banker are among the minority that thinks the report

will make a difference. "Let's face it, the malaise is

a political one," says Gerson DaCunha, the first CEO

of Bombay First. "We have always been saddled with criminal

administrators with narrow self-interests." Darryl D'Monte,

a journalist and environmentalist who is involved in Bombay

First, has the last word. When asked whether he can name a

single effort involving citizens, the government, and corporates,

his response is a crisp, "no". That's one reason

Bangalore, more than Mumbai, is better placed to be India's

city of the future.

|

In February, this year, Srikanth Nadhamuni,

formerly part of Sun Microsystem's Ultra Sparc development team

and Jim Clark's start-up Healtheon/Web MD, attended his first BATF

Summit, a large gathering of citizens, NGOs from Bangalore and other

parts of India, BATF members, the city's departments, and representatives

from other states. "I was blown away," says Nadhamuni.

"Bureaucrats were actually presenting six-monthly report cards."

The seven stakeholders of the BATF (See The

Bangalore Ecosystem...), or so the joke goes in Bangalore, have

become good at PowerPoint presentations. At every summit, the head

of each of the seven departments makes a presentation on what his

organisation has achieved in the preceding six months, and what

it proposes to in the following six. "The summit concept recognises

the contribution of bureaucrats," says Nilekani. "And

it also facilitates continuity-if a bureaucrat is transferred, it

ensures that the next one sticks to the commitments.''

Even without the summit, Cityhall is unlikely

to return to the Dark Ages. In mid-2001, armed with the knowledge

that BMP's f-bas could provide details on the exact amount of money

that was earmarked for ward works in the corporation's budget, Ramanathan

suggested that citizens participate in the process of deciding how

this money was spent. The corporation shot his proposal down. Frustrated,

he founded Janaagraha a citizen's movement. "For citizens to

think that enlightened political leadership is all it takes for

good governance is unrealistic and selfish," explains Ramanathan.

So, across the city's 100 wards, Janaagrahis, as the movement's

volunteers call themselves, wrote to their local corporators suggesting

how the money earmarked for ward works in their area could be best

utilised; in 22 of the wards, their recommendations were adopted.

Ramanathan is thrilled with the results. He sees this as the beginning

of a move from "representative democracy to participative democracy".

That's a trend that will be difficult to reverse.

India's economic progress, patchy as it may

be, has brought with it a growing awareness of citizens' rights

across the country. Today, eight states, including Karnataka, have

passed a Right to Information Bill. So, in July 2002, Janaagraha,

PAC, Voices, a Bangalore-based development communications organisation,

and the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, a research body working

in the area of sustainable and equitable development, launched proof

(Public Record Of Operations and Finance), a right-to-information

campaign that aims to define the reporting standards for government

performance. Apart from providing citizens with a framework to assess

the performance of their government, this will help NGOs working

from within the system-a preferred Bangalore model-to assess theirs.

For instance, Akshara Foundation, a Bangalore-based NGO that has

signed an MoU with the government to help with educational initiatives

across 1,300 schools (it is headed by Rohini Nilekani) will use

proof's framework of performance indicators to assess its impact.

| Bangalore's Success-Ingredient #5: Appraisal

Systems |

By design or providence, the pieces have come

together for Bangalore. Systemic interventions such as f-bas have

made information available, where none was before. Campaigns like

proof will, over time, make it mandatory for government bodies to

report their performance in the lexicon of business. And Janaagraha

is, as Ramanathan terms it, "an endgame", an apt "demand

side" response to "supply-side reform".

In 1954, American psychologist Abraham Maslow

defined his hierarchy of needs theory as explanation for what motivates

people. Three decades after his death, Maslow's pyramid is still

relevant-although newer theories have taken some sheen off it. At

the base of the pyramid are lower order needs such as food, clothing

and shelter.

At the apex of his heirarchy is what Maslow

termed self-actualisation, a term so nebulous that he felt the need

to redefine it in 1968. Put simply, a self-actualised individual

has become all that he or she had the potential to be, and consequently,

looks for causes to champion that are outside one's own selfish

frame of interest.

Harish Bijoor believes Bangalore is where it

is today because its citizens, at least those involved in city-improvement

initiatives, are self-actualised. Bijoor has something there: Ravichandar,

Ramanathan, Nadhamuni, Kar, Nilekani, and others at the vanguard

of Bangalore's renaissance have been there, done that; money, power,

and recognition don't really matter to them anymore. "If you

were to look at it in terms of proportions," says Public Affairs

Centre's Paul, "Bangalore has more professionals than any other

Indian city", proffering his own explanation for the city's

renaissance. Raghavan Srinivasan, Executive Director of market research

agency TNS Mode-it conducts reviews of citizen concerns for BATF-argues

that Bangalore has always been a city of NGOs thanks to its R&D,

defence and public sector heritage ("Post retirement several

people from these backgrounds started NGOs or signed on with them")

and that its private industry is largely knowledge-oriented and,

ergo, "has no baggage and believes it can make a difference."

And Kar insists that timing-BATF was founded at the cusp of an era

of hope; the software boom was on; and the dotcom bust was yet to

happen-helped. Add things like political will and what Krishna calls

"bureaucratic guts" and you get a mixture that pretty

much cannot be replicated.

What can be are the processes that, says Nilekani,

can be "packaged, productised, and replicated". "We're

using the software model for governance," he gloats. "The

f-bas kit, the complete documentation on toilets-everything is open

source, free-ware." Nadhamuni, Managing Trustee, eGovernments

Foundation, is the man in charge of this effort.

Nadhamuni and his wife Sunita moved back to

India a few months ago after 16 years in the US. They had funded

NGOs back home for 12 of those years and hoped to immerse themselves

in developmental work on their return. The BATF Summit and awareness

of what was happening in Bangalore convinced Nadhamuni that "this

is the place to get plugged in".

Wiring up individual processes, such as BMP's

Self Assesment Service for the collection of property tax, even

a F-bas is not so difficult. Nadhamuni's Holy Grail is a technology

for e-governance that can be replicated across a fairly large geography,

facilitates distributed decision-making and widespread access, and

is web-enabled. He believes a Geographical Information System (GIS)

is the answer and is currently working on a pilot project to map

Byatrayanapura, a borough that falls within the purview of the larger

City Municipal Corporation. "I am creating a virtual team of

volunteers to do this," he laughs. "There is so much work

and they can do it from anywhere in the world; do you think you

could mention our website, www.egovernments.org ?"

TNS Mode's surveys (see Progress Has Been Made...)

definitely indicate an improvement in quality-of-life parameters.

"In a growing city like Bangalore, you have to run to stay

where you are," says the agency's Raghavan. "So, a small

improvement is actually a big deal." Industry sure thinks so.

Ketan Sampat, President of Intel India announced last month that

the company is investing an additional $41 million (Rs 188.6 crore)

in building a new 43-acre campus in Bangalore. Intel is believed

to have picked Bangalore after examining six other Indian cities.

And two days after Premji's tirade, Krishna instituted a task force

headed by the chief secretary to look into his grievances.

Bangalore still has ways to go before it becomes

a Singapore in India. Given the gravity of some of its problems,

it may take quite some time for that to come to pass, and there's

a good chance that it never will. "As long as I am headed even

North by Northwest I am willing to plug on," says Ravichandar.

The future of Indian cities is here. Bangalore is it.

-with additional inputs from Venkatesha

Babu, E. Kumar Sharma, Sahad P.V.,

Priya Srinivasan, and Nitya Varadarajan

|