|

|

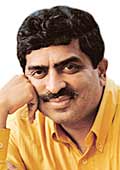

| Infy's Four Fast Man: (From

left) N.R. Narayana Murthy, Chairman and Chief Mentor, T.V.

Mohandas Pai, Chief Financial Officer, Nandan Nilekani, President

and CEO, and S. Gopalakrishnan (Kris), COO |

18 kilometres

from Bangalore's city-centre, down Hosur Road with its glass-and-chrome

monuments to the city's reigning business is a company that sees

itself as India's Wal-Mart. If Bangalore is the heart of the IT

Nation India wants to be, the traffic-clogged road is one of its

main arteries (and it is in sore need of a bypass). Heads of state

have travelled down this technology boulevard to visit the company,

as have chief executives of multinational corporations, ambassadors

of and journalists from countries large and small, Indian politicians

and businessmen, schoolchildren out on field trips, even the odd

film star or two. All have marvelled at the manicured lawns, the

extensive food-courts, a Grecian amphitheatre aptly named Pythagoras,

a futuristic experience theatre, and the other architectural wonders

that have to be described thus simply because most Indian companies

cannot claim to have anything of the kind, and nearly all of the

few that can were inspired by this company. There's little visible

evidence, though, of its link with Wal-Mart. The retail giant closed

2003 with revenues of $256.33 billion (around Rs 1,200,000 crore,

43 per cent of India's Gross Domestic Product for 2003-04), profits

of $9.05 billion (around Rs 42000 crore), and 1.4 million employees.

The Bangalore company closed 2003-04 with revenues of Rs 4852.95

crore, profits of Rs 1,243.63 crore, and 25,634 employees.

It isn't bravado that makes Infosys Technologies

see itself as India's Wal-Mart, explains the company's CEO Nandan

M. Nilekani; it is sound business logic. Nilekani is a cheery 49-year

old; a graduate of Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, he is

one of the company's six co-founders, and since March 2002 has served

as its CEO, President, and Managing Director. He has obviously thought

long and hard about the Wal-Mart thing and launches into a rather

professorial exposition of the strategy. At the core of this explanation

are what Nilekani terms business platforms, "scalable engines"

that help a company do something well, very well. "Wal-Mart

has a scalable engine for retailing," he says. "Dell has

one for (direct selling) technology products." Nilekani peppers

his discourse with facts: Wal-Mart did not start selling groceries

till 1998 but now accounts for 15 per cent of groceries sold in

the US; Wal-Mart started selling petrol (gasoline in its lingo)

in 1997 and now accounts for 7 per cent of the commodity sold in

the US. "We have a scalable engine for software services,"

he concludes. "Scalability is the name of the game," adds

N.R. Narayana Murthy, Chairman and Chief Mentor, Infosys, who does

his reputation of being an obsessive long-term manager no harm at

all by observing that it is possible that the company will employ

50,000 people in India and 20,000 in China in the next three-to-five

years (the company has subsidiaries in China and Australia). "We

have a 4,000-bed training campus," he says, referring to the

Infosys Leadership Institute in Mysore. "Three-to-four years

from now, we may well have to train 40,000 people."

N.R.

Narayana Murthy

Chairman and Chief Mentor

Mr. Values. Apart from everything else (itinerant seller of

India on behalf of Confederation of Indian Industry, Chairman

of the board of Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, member

of the board of Reserve Bank of India, and more of the same),

Murthy is Infosys' in-house Ombudsman and conscience keeper.

He also finds the time to carry out a quality review of one

project every three weeks (the company's head of quality has

confirmed appointments with him for the next 24 months). Two

of his articulated obsessions have found their way into the

vocabulary of every senior manager at Infosys: "Excellence

in execution", and "What is the five-year impact of

this?"

Nandan Nilekani

President and CEO

Mr. Strategy. Always the big picture man, Nilekani is behind

Infosys' new Wal-Mart plus strategy. Its essence: build a

super-efficient platform that can offer the entire range of

software services, from consulting to Business Process Outsourcing

(much like Wal-Mart has, the retail platform to sell everything

from DVD players to petrol to groceries), and layer it over

with new initiatives, such as the emphasis on business solutions,

to ensure that the company doesn't fall into a commodity trap.

T.V. Mohandas Pai

Chief Financial Officer

Mr. Finance. The man who usually hogs the limelight at the

company's televised quarterly announcement of financial results.

Pai doesn't just count the money, however, he spends a bit

of it: as the person responsible for Infosys' campuses, this

year he will burn anything between Rs 600 and Rs 750 crore

on physical and communication infrastructure.

S. Gopalakrishnan (Kris)

COO

Mr. Operations. Infosys had 27,939 people on its rolls and

419 active clients as of June 30, 2004. This translates into

1,400 to 1,800 projects at any point in time. Kris keeps the

machine going.

|

There's a price to pay for the single-minded

pursuit of scale: the product or service the company sells becomes

a commodity, and profit margins plummet. To avoid this fate, Infosys

has embarked on a six-pronged differentiation strategy: applying

the global delivery model that works so well for it in application

development to consulting (it invested $20 million, around Rs 925

crore, and created Infosys Consulting in April this year); bundling

business processes, technology, and transactions into one service

that delivers business productivity; experimenting with the global

delivery model of the future; evangelising a new model of sourcing;

offering companies business solutions; and leveraging alliances

with technology companies big and small (think Microsoft, think

Yantra) to ensure that solutions are built around existing technologies,

when available. Some of these, explains S. Gopalakrishnan, Chief

Operating Officer, Infosys, will help the company "bid for

larger projects". Others, will establish it as a thought leader

in the outsourcing space. And still others, "disrupt the business

of consulting the same way we did the business of application development."

Some strands of this Wal-Mart-plus strategy

are almost as old as, well, Infosys' Heritage Building (1994-vintage).

Others are more recent, but it is only now that everything has come

together into a greater whole. It is almost as if, for the first

time since the early 2000s when India's software services companies

discovered that they too were vulnerable to long-term business cycles,

Infosys has a clear idea of where it wants to be in the future,

and how it plans to get there.

The software services business looks simple

from the outside as indeed, most businesses, including magazine

publishing do. Companies slap together a development team in India,

nab contracts in the US, Europe, or Japan (everywhere else is largely

an afterthought even today), offshore the work to India, then, after

the project is done implement it onsite with a small team. The seeming

simplicity of this model has been the undoing of entrepreneurs,

including defecting senior executives from companies such as Infosys,

Wipro, and TCS, who jumped into the business with dollar dreams

in their eyes. Companies, analysts, and consultants who track trends

in the industry have come around to the view that the prerequisites

for success in the software business can be distilled into two key

skills: the ability to offer a range of services and offer them

in increasing volumes and the ability to take a process, offshore

it, and then deliver the desired result to the customer (this part

is roughly what the industry calls the Global Delivery Model).

| THE SCALE INITIATIVES |

The

company has built the processes to recruit the kind of numbers

it will need. Last year, Infosys received over 1

million applications, tested around 130,000 candidates,

and hired around 10,000. This year, it will hire between 8,000

and 10,000 The

company has built the processes to recruit the kind of numbers

it will need. Last year, Infosys received over 1

million applications, tested around 130,000 candidates,

and hired around 10,000. This year, it will hire between 8,000

and 10,000

Infosys can build a full-fledged

campus (500,000 square feet of built-up area) in six

to nine months. As on June 30, 2004, the company had work

in progress of some 2.7 million square feet

Process Repository@Infosys for

Delivering Excellence, PRIDE isn't just something that helps

everyone work the Infosys way; it also doubles up as a development

environment

Some 60-65 per cent of Infosys' processes are completely

digital

Late last year, Infosys broke itself up into what one executive

calls "many small Infosyses",

some 17 independent business units (IBUs) and Enterprise Capability

Units (ECUs). Nilekani claims this has created "multiple

engines of growth"

Infosys can train numbers and how! Its leadership institute

at Mysore can accommodate 4,000 people (in residential programmes).

Last year, the company ran around 1,500

management development and 2,000 technical development programmes

|

| DIFFERENTIATION INITIATIVES |

| Infosys Consulting, Inc. is what Nilekani terms

a "quasi-acquisition model".

Rather than acquire a consulting firm in the US, the company

has hired a selection of senior consultants, many brands in

their own right, and incentivised them to grow the offshore

business

The company's new structure makes it possible for the business

units to develop and market business solutions unique

to their industries

Infosys Australia is working on a new

global delivery model that involves substantial work

being done onshore

Infosys is playing evangelist to a new model of sourcing

it calls modular outsourcing

Infosys is leveraging partnerships with Microsoft,

Oracle, and SAP

Infosys and Progeon, its IT-enabled services subsidiary,

are working on delivering business productivity by bundling

business processes, technology, and transactions

|

| FIVE TO EIGHT YEAR STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS |

ANNUAL STRATEGIC PLANNING:

Identification of themes relevant to the company.

STRATEGIC IMPLEMENTATION: InfyPlus,

a change management programme

COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS: A five-year

model of the competition (factors in types of competition, such

as other Indian companies and multinationals, and individual

competitors, such as Wipro and IBM)

SCENARIO PLANNING: A what-if

exercise that looks at everything from the rupee-dollar dynamics

to new technologies |

| THREE-YEAR BUSINESS PLANNING PROCESS |

BUSINESS PLANNING: Each

business unit has a very specific plan.

GOAL ALIGNMENT: A mechanism to

ensure units are moving towards stated goals

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT: An analysis

of the business units; investment-decisions are based on this

FIVE-YEAR MODELLING: A quantitative

model of the company (refined enough to come up with the implications

of a particular decision on profitability) |

| CURRENT YEAR OPERATIONS ASSURANCE PROCESS |

RESOURCE PLANNING:

Space and infrastructure requirements

BUDGETING: A process involving

quarterly realignment for the following four quarters

RISK MANAGEMENT: A robust model

that incorporates an eight-step risk management process and

which can combat four types of fisk (strategic, operational,

reporting, and compliance) at four levels (entity, business

division, functional, and subsidiary)

OPERATIONAL REVIEW |

If this magazine were a management journal-it

thankfully isn't that-this is where this composition would depart

from the style of popular business journalism and launch into a

jargon-filled description of how Infosys has, or is in the process

of institutionalising these two abilities. We will remain content

with a graphical representation of the thrumming corporate planning

engine that makes it possible (See the Five to Eight Year Strategic

Planning Process on page 43). This is the domain of Sanjay Purohit,

a 38-year-old engineer who once worked for Tata Sons auditing the

quality processes of all companies belonging to the Tata Group.

These days, he is the custodian of a planning process that spans

three time-horizons, one year, three years, and five-to-eight years,

and, among other things maintains a highly refined mathematical

model of Infosys (Want to know the impact of a certain decision

on the company's profitability in two years? Ask Purohit) and rudimentary

ones of around 10 competitors, Indian and multinational (Wipro,

TCS, and IBM are there). One of Purohit's responsibilities is to

ensure that the three temporal horizons are aligned. Another is

to run the whole process like a democracy. For instance, his department

starts work on the five-to-eight year strategic planning process

every July; it scans the environment, studies the competition, crunches

its models and then makes a presentation to the board; this is followed

by a presentation to the company's top 80, then top 200 managers.

|

|

| Bigger, not necessarily better:

TCS' S. Ramadorai (L) and Wipro's Azim Premji head firms

that are larger than Infosys |

The best strategy, to paraphrase management

theorist Alfred Chandler-Honest, this is the last reference to management

in this article; this writer's own preference in Chandlers is more

Raymond than Alfred-is wasted without the right structure. In November

2003, Infosys restructured itself into 17 independent business units

(IBUs) and enterprise capability units (ECUs).

The result of this strategy-structure interplay

(each IBU or ECU, for instance, has its own detailed three-year

business plan) is a set of requirements: of skills that need to

be acquired, markets that need to be penetrated, people who need

to be hired, campuses that need to be built, and money that needs

to be spent. Mohandas Pai, the company's CFO who doubles up as the

man responsible for infrastructure, acquires land and builds campuses

on the basis of this. Hema Ravichandar, Infosys' head of hr tweaks

her recruitment engine-it processed over a million applications

in 2003-04-accordingly. And everything, the building, the hiring,

the training, revolves around a process that is, more often than

not, digital. Then, that's only apt.

Sivshankar J. is a techie's techie. The ever-smiling

bearded 44-year- old is the company's head of information systems

and he and his team of 200 have digitised almost 65 per cent of

Infosys' internal processes. In layspeak that means that in the

case of most processes, the company has a nervous system that ensures

that something is done just the way it is meant to be, every time.

A sample: if a project manager forgets to get the budget for a project

approved, he cannot get anyone working on the project to travel;

worse, the people assigned to the project automatically revert to

the bench. Now, an organisation of 200 can have one or two people

who track such things manually; an organisation of 25,000 cannot;

it needs systems, and it needs systems that can talk to other systems.

The project-travel-bench example is part of a larger order to receipt

(OTR) system and Sivshankar is quick to point out that the system

gives enough time for the project manager to get his project approved.

"The system will block the ticket but it will not issue it,"

he says. "The objective is not to get in the way."

| NOT EVERYONE'S FAVOURITE |

| Bangalore isn't

short of people willing to bad-mouth Infosys, and not all are

former employees. There are charges that with four of the founders

still occupying key executive positions-Nilekani is CEO, Gopalakrishnan,

COO, S.D. Shibulal is head of delivery, and K. Dinesh, Director-and

likely to do so for some time, senior executives come up against

an invisible ceiling. That doesn't seem to have had any impact

on the careers of CFO Mohandas Pai, Head of HR Hema Ravichandar,

and Srinath Batni, an executive member of the board. There are

also allegations that the company's marketing function has never

really recovered from the exit of former head of sales and marketing

Phaneesh Murthy. Yet, Infosys has continued to grow faster than

the competition. And finally, there is a constant buzz about

how dissatisfied employees are departing Infosys in droves.

Things came to a head last June; poor employee satisfaction

scores saw Infosys, which had twice been named the best company

to work for in India, according to a survey featured in this

magazine, not even figuring among the top 10. This year has

been better for Infosys' head of HR Hema Ravichandar: although

attrition (Last Twelve Months basis) was 10.9 per cent on June

30, 2004, as compared to 7.9 per cent on June 30, 2004, there

aren't too many reports of an exodus. One reason for that could

be the fact that with a revival in the fortunes of the software

sector, attrition rates are up in most organisations. Every

Wednesday, the Bangalore edition of the Times of India comes

with Ascent, a jobs supplement. That morning, when Infosys employees

board the bus that takes them to the company's campus, they

find that someone has helpfully stocked the vehicle with enough

copies of the daily. More are shoved in through windows when

the bus stops at traffic lights. Wipro's Chairman Azim Premji

recently rued the high attrition rate at his company (the buzz

says 16-18 per cent) and linked it to Bangalore's infrastructural

inadequacies. Ravichandar believes the company's efforts at

moving to a role-based organisation, defining salary bands for

jobs, increasing the component of variable pay in overall compensation,

and putting a stop to the wide-spread industry practice of promoting

people just because they have spent a certain period of time

in the organisation, have helped in terms of employee satisfaction.

She steers clear of it, but the Rs 100 crore the company doled

out as bonuses to employees when it crossed $1 billion in sales

earlier this year must have helped too. |

Sometime in July 2003, Nilekani thought it would

be a good idea to extend this systems-driven approach to work processes.

The result, which went live in March this year is PR@IDE (Process

Repository @Infosys for Delivering Excellence). From creating a

proposal for a customer to designing an integration process to assimilate

an acquisition, PR@IDE is an online, and much-more advanced version

of everything from the ubiquitous style manual floating around newspaper

offices to the renowned Toyota Production System, the pinnacle of

manufacturing perfection. It is also linked to the company's knowledge

management system and can not only list the tools that can be used

in a process, but take the user to the relevant development environment.

That's something: in an industry well-known for chaotic processes,

it ensures that everyone within the company works the Infosys way,

right down to the code jocks.

Circa June 2004, Infosys has enough benefits

of scale to display. Differentia-tion, Nilekani admits, will take

some time to pay off, maybe two or three years. And when it does

it will likely manifest itself as an increase in the company's revenue

productivity (revenue per employee). This, when the analyst community

is convinced that the company is ahead of its peers on this metric.

"In terms of margins (profitability) and employee productivity,

Infosys is well ahead of Wipro and TCS," says Chandan Desai,

a director at Mumbai-brokerage TAIB Securities. Nilekani is right:

Infosys Consulting is four months old; the emphasis on business

solutions has been around for some time, but has come into its own

only after the November 2003 restructuring; the global delivery

model of the future is a recent project (it is happening at Infosys

Australia, which the company acquired earlier this year); the modular

outsourcing thingamajig was unveiled by the company last May and

the integrated it and it-enabled services offering is of recent

vintage too.

|

Hema Ravichandar

HR Head/Infosys |

| Her department processed over a million applicants

last year, and hired 10,000 |

That could explain why a senior executive at

one of the main competitors dismisses Infosys as a company still

"over-dependant on application, maintenance and development"

and "hugely exposed to banking, insurance, and financial services".

Both are accurate observations: for the three months ended June

30, 2004, development and maintenance accounted for 55 per cent

of Infosys' revenues; insurance, banking and financial services

for 34 per cent. Wipro has a more diversified revenue pie and TCS

is far bigger. Still, Infosys is a favourite on D-street. Analysts

point to the company's performance in 2001-02 and 2002-03, when

most other software companies, including its peers stumbled, as

reason for this bias. "While TCS has the scale, Infosys has

the efficiency," says Sandeep Shenoy, the head of research

at Mumbai brokerage Pioneer Intermediaries, who expects the latter

to overtake the former in terms of revenues and profits in the next

two-to-three years. Infosys' senior managers refuse to be drawn

into a who-is-bigger discussion, but it is evident that they are

convinced the Wal-Mart-plus approach will work. "The results

are there," says Murthy referring to the fact that the company

has grown in times good and bad. He pauses, as if running all the

initiatives the company is working on through his mind. "It

will happen."

-additional reporting by Narendra

Nathan

|