|

Circa

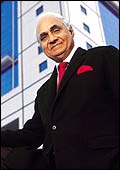

1981: it's a hot summer day in Gurgaon (Haryana), and K.P. Singh

is seated on a charpoy next to a tubewell, talking to a villager.

Except for some patches of greenery, the expanse around him is brown

and barren. Circa

1981: it's a hot summer day in Gurgaon (Haryana), and K.P. Singh

is seated on a charpoy next to a tubewell, talking to a villager.

Except for some patches of greenery, the expanse around him is brown

and barren.

The 49-year-old Singh has spent the better

part of the morning trying to convince the villager to part with

his ancestral land so that Singh's real estate development company

can add to its modest landpool of 150 acres or so in Gurgaon. Just

then, a jeep comes screeching onto the dirt track close by to where

Singh and the villager are seated. A few meters into the jagged

stretch, the jeep sputters to a halt.

While the driver takes a look at the problem,

the jeep's occupant-a young, sophisticated man-decides to come out

and bide his time with Singh on the charpoy. They get talking. The

visitor has heard of DLF and asks Singh why he hasn't put to use

the land DLF owns. Singh tells him that existing regulations don't

allow private sector development of townships. ''Laws can be changed,

right?'' asks the young man. ''Sure, but we've been trying for years

now,'' replies Singh.

Three years later, when the young man became

India's Prime Minister, laws would be amended to allow private companies

to build townships. The man Singh met on that fateful day was Rajiv

Gandhi.

|

The Man

|

|

Name: Kushal Pal Singh

Born:

August 15, 1931

Education: Bachelor of Science, UK

First Employer:

Indian Army (Deccan Horse Regiment)

Joined DLF:

1961

Claim To Fame:

3,000-acre DLF City, Gurgaon

Inspiration:

Father-in-law Chaudhary Raghvendra Singh; former GE CEO, Jack

Welch; and George Hoddy, CEO Universal Electric

Hobbies:

Golf, tennis, music, and art collection

Favourite painters:

M.F. Hussain, Paramjit Singh, Satish Gujral

Favourite Golf Course:

DLF (India), Pebble beach (US)

Golf Handicap:

18

Family:

Indira (wife), Rajiv (son), Renuka Talwar, and Pia Singh (daughters)

Trademark:

Maroon silk kerchief in coat breast pocket

Car: (Obsidian

Black Metallic) Mercedes Benz E-230

Dream:

To make DLF an instrument of social change

|

|

The Empire

|

Companies: DLF Universal and 40 subsidiaries

Group Turnover: Rs 400 crore

Profits: Rs 43 crore

Real Estate Domain: DLF City, Gurgaon

Acreage: 3,000

Total Residential Units: 20,000

Total Commercial Space: 14 lakh sq ft

Raw Materials Consumed: 1 lakh tonnes of steel, and

7.25 lakh cubic metre of concrete

Daily Rentals: Fast approaching

Rs 1 crore

USP: Built India's only integrated private township

Market Value of DLF City: An estimated Rs 50,000 crore |

January, 2002: ''What do you see?'' asks Singh,

scanning the grey evening horizon in front of him. From atop the

21-storey DLF Square in Gurgaon, the sight is one of a bustling

city. Hundreds of townhouses dot the green landscape, interrupted

by imposing, multi-storeyed buildings-some built and the others

under construction, like the 532-unit Belvedere Park & Tower.

You tell him so.

''Wrong,'' pat comes the reply. ''What I see

is a city whose young residents tomorrow will change the face of

the nation. Here, for instance,'' he points to some 80-odd acre

of vacant land in between DLF Square and the signature Gateway Tower,

''we will build the world's best cybercity that will put Haryana

on the IT map. Development is meaningless if it does not bring prosperity

to people in and around it.''

Coming from somebody else in the murky world

of real estate, that would have been a good joke. But this is Kushal

Pal Singh. Less than two decades ago, he bet his company on Delhi

moving further south to Gurgaon. Today, at 69, Singh is India's

richest and most successful real estate tycoon. His 3,000-acre DLF

City in Gurgaon is the only integrated township of its kind in India.

Sure, the Hiranandanis and Rahejas of Mumbai are big names too,

and have world-class apartments in places like Powai, Kandivali,

and Borivali. But in terms of sheer size, DLF City is unmatched.

Consider: the DLF city has 20,000 residential units and 14 lakh

sq. ft of India's best commercial property. Concedes rival and friend,

Sushil Ansal, 62, Chairman, Ansal Properties and Industries: ''One

needs to have vision and leadership to achieve what KP has.''

Most companies that have put down roots in

Gurgaon have leased, not bought, real estate from DLF. Thus, while

the rentals appear on DLF's financial statements, the true value

of the assets doesn't. Therefore, while DLF Universal's balance

sheet shows a purchase price gross assets of Rs 648 crore, real

estate experts estimate that DLF City at today's market rates would

be worth anywhere between Rs 40,000 crore and Rs 50,000 crore. Since

Singh owns 95 per cent of the company, he should easily be one of

India's richest men.

Like Donald Trump, who started his business

with a million or two borrowed from his father, Singh inherited

the company, and did nothing spectacular with it till he discovered

Gurgaon in the 1980s. Today, the one-time village of Gurgaon is

well on its way to becoming one of the best satellite cities in

the country (See Gurgaon: Suburban Success).

|

| One reason why dlf City ticks is that it

marries modernity with the quaint 'walk-to-work' concept. But

access to Delhi is still a problem. |

"Damn Lucky Fellow"

For Singh, it seems fate conspired repeatedly

to make him a real estate tycoon. Just like the Rajiv Gandhi episode,

events happened in Singh's life that foreordained his success. Born

into a family of successful lawyers in Bulandshehar (Uttar Pradesh)

on August 15, 1931, Singh went on to join the Royal Military Academy

at Sandhurst (UK), and on graduating with a degree in science, was

coaxed into joining Deccan Horse-the cavalry regiment of the British-Indian

Army by General M.S. Wadalia. But fate had other plans.

Wadalia was so impressed with the young officer's

diligence and sincerity that he recommended him as a groom for a

daughter of his friend, Chaudhary Raghvendra Singh. The Chaudhary

came from a landed agricultural family and was a provincial (Punjab)

civil services man, and while still in his mid-thirties realised

that the coming Partition would mean having to rehabilitate thousands

of displaced people. That's when it became apparent to him that

real estate was as good as any business to get into. Therefore,

on September 18, 1946, Raghvendra Singh launched Delhi Land and

Finance. But he rarely called his company that, preferring to use

the abbreviated form. And whenever he was asked what DLF stood for,

he'd quip: ''Damn Lucky Fellow''.

The real Damn Lucky Fellow, KP, would arrive

only eight years later in 1954, when on March 6 he tied the knot

with Raghvendra Singh's eldest daughter, Indira. Post partition,

Raghvendra Singh had established DLF as Delhi's leading realty firm.

Between 1949 and 1954, he had developed more than a dozen townships

in and around Delhi, including South Extension, and Greater Kailash.

When KP became part of the family, Raghvendra Singh, as much as

Indira, instantly fell in love with the six-foot-two, swashbuckling

Army captain, who won hearts over not only with his good looks but

also impeccable manners and keen intellect.

|

| K.P. Singh with his family at his home on Delhi's

Aurangzeb Road |

| One reason why dlf City ticks is that it

marries modernity with the quaint 'walk-to-work' concept. But

access to Delhi is still a problem. |

Therefore, even though Raghvendra Singh got

another son-in-law in Major Shamsher Singh (who married Prem Mohini),

KP was his favourite, being cast in the same mould as he. Says Bharat

Ram, 84, Chairman of SRF and a friend of Raghvendra Singh: ''Raghvendra

was a man of standing himself, but KP brought a new touch of aristocracy

and sophistication to DLF.''

Yet, the young KP had first to cut his teeth

on different DLF companies, Willard India and American Electric

Universal (it made fractional motors), where he tried to keep a

small and unprofitable business afloat. In 1971, he moved over to

the real estate business, when it became clear that the smaller

companies were headed nowhere. But those years weren't the best

of times. The Delhi Development Authority Act of 1957 had made land

development a state monopoly, and DLF was only allowed to work on

projects either already underway or approved prior to the act. The

result: DLF, which once was racing ahead, lost steam. Between 1958

and 1981, it executed only seven big projects.

DLF's record in businesses other than real

estate hasn't been impressive. American Electric suffered from a

lack of business and was sold to GE Motors; DLF Cement, with a 1.5

million tonne plant in Rajasthan, became a BIFR case and in 2000

was sold to Gujarat Ambuja for Rs 142 crore. The only exception

seems to be DLF Power, which despite its modest Rs 100 crore turnover

raked in Rs 15 crore of net profits last year. In fact, had Gurgaon

not happened, chances are, you wouldn't be reading this article.

| GURGAON: SUBURBAN SUCCESS |

|

Mumbai

has vashi, chennai has tambaram and Neelankarai, and Bangalore,

Whitefield. But none of them has been able to attract top-notch

mncs and a breed of young, successful, and rich executives

the way DLF City in Gurgaon has. A big part of the reason

is easily explained: Gurgaon is closer and more accessible

to the mother city (in its case, Delhi). But another driver

of the success is DLF itself. Not only has the company created

some of the best corporate buildings in India, but also the

finest residential complexes. Says Anshuman Magazine, Managing

Director (South Asia), CB Richard Ellis: ''Since dlf entered

Gurgaon first, it has some of the best locations and best

commercial buildings. In fact, they've built the city on 'walk-to-work'

concept,'' (through a mix offices and homes).

According to the Haryana government's

urban development plan, Gurgaon has a total area of 24,702

acres, of which close to 16,000 acres is earmarked for residential

units and the rest for industry. DLF itself has 3,000 acres

of which about 600 acres is still undeveloped. Currently,

it has 14 lakh square feet of commercial space, with an average

monthly rental of Rs 40 per square feet. An A-grade property

in Connaught Place (New Delhi), in comparison, costs Rs 100

per month, without the guaranteed parking space and 100 per

cent power back up that DLF offers in Gurgaon.

Going forward, KP's plan is to build

some 60 million square feet of commercial space, anchored

by an 85-acre CyberCity to be built at a cost upwards of Rs

1,500 crore. The focus is on attracting call-centre operators

and more software and technology companies. In fact, some

people close to the company, also believe that upmarket casinos

may be opened in DLF City sometime in the future. But did

DLF miss a good opportunity to build a more planned city?

Sure, it has been built up in phases (I to V), but unlike

Vashi (which despite its clutter is planned), it does not

give a composite feel. Let's see if KP can do something about

that.

|

The Jack Welch Effect

Luckily for KP, two things happened in the

80s. One, Rajiv Gandhi paved the way for private sector's entry

into township development. And KP came into contact with General

Electric's (GE's) new CEO, Jack Welch. The how of it must be told

because it symbolises something germane to KP. The story goes like

this: Sometime in the early 80s, KP was introduced to Jack Welch

at a New York dinner party as a real estate entrepreneur from India.

Welch-who was bristling with the loss of an aircraft engine order

from Air India, reportedly because a corrupt rival had bribed Indian

officials-minced no words in telling KP what he thought of India.

On that bitter note, KP's acquaintance with

Welch should have ended. But fate, in the form of Rajiv Gandhi,

intervened again. As the new Prime Minister, Gandhi was trying to

woo foreign investors, and his invitation for a dinner meet in India

was spurned by Welch. The PMO, meanwhile, had learnt that KP had

met Welch in New York. His services were requisitioned, and fortunately

for India, KP was scheduled to make another trip to New York. Ahead

of that, he investigated the Air India deal and found that GE was

not the lowest-price bidder as Welch had been told by his executives.

Upon meeting Welch, KP bared the truth. And as if to make up for

his initial rudeness, Welch agreed to visit India and meet with

Gandhi. In Welch's own words, ''After that trip, I became the champion

for India'' (See Welch on Singh).

A few years ahead of changes in land development

laws, KP displayed remarkable foresight and started buying pockets

of land in Gurgaon, anticipating Delhi's shift further south into

Haryana. But his holdings were small. The meetings with Welch had

exposed him to the American CEO's 'lead or leave' philosophy-that

pursuing a business was worth it only if the company could be number

one or at least number two in the industry. ''DLF is what it is

today because of Jack's influence on me,'' admits KP as a matter

of fact.

|