|

AGRICULTURE

Sukhjit Singh Aulakh at his farm near Jalandhar

India is the world's largest producer

of farm commodities, and the second- largest producer of fruits

and vegetables. Yet, less than 2 per cent of its fruits and

vegetables are processed. Simply organising the farm supply

chain can transform fortunes of the farmers. |

From

atop Sukhjit Singh Aulakh's Farmtrac 60, life looks just as it should:

beautiful. The winter sun is warm and golden, and his 52-acre farm

in Adampur near Jalandhar is lush green with promise. The 40-day-old

potato crop is coming along nicely; a huge tract of sugarcane has

already been cut, and the rest will reach the market too in a few

days. The 39-year-old Aulakh's two children-a 11-year-old son and

a four-year-younger daughter-go to a "convent" school

("It's not top-class, but it's good," says the man), and

his two brothers work in Canada, where Aulakh himself worked before

returning to India to manage affairs after his father's death. It's

been eight years since, but the trendy Aulakh-dressed in Levi's

sweatshirt and jeans, and Lotus Bawa sneakers-has "no plans

of going back to Canada".

Why should he? Since the early 90s, the Pepsi

contract farmer's yields have soared. Earlier, his farm used to

produce nine tonnes of potato per acre. Now-with help from Pepsi's

agri-scientists-it is 20 tonnes-plus. In the mid 90s, he'd be happy

if he eked out 2.5 tonnes of red chilly per acre. Now he gets three

times that, but believes his potential as a farmer is still not

being tapped fully. "If we get marketing help, we can take

on any country in potato and wheat in the global market," says

Aulakh.

THE PROMISE OF TOMORROW

Five reasons why India could become the

next economic powerhouse. |

Human Capital: No other

country has cheap and intelligent workforce like India does,

and that means the country can do everything from cheap assembly

to high-tech research.

Middle Class: Its purchasing power may

be limited, but there's no denying that India's middle class

of 300 million could be the biggest consumer of everything from

cereals to cars.

Natural Resources: With the

exception of the US, few of the top economies can match the

natural resources India has. If tapped effectively, this could

be a crucial competitive advantage.

Democracy: In the long run, foreign investors

would prefer countries that have strong legal and democratic

systems. With some clean up in bureaucracy, this can work to

India's advantage too.

Diaspora: Unlike China, India may not

have a strong flowback from its non-resident population. But

the diaspora serves as a role model for India's aspiring millions. |

Replace the name Sukhjit Singh Aulakh with India,

and you might as well be looking at a metaphor for modern India.

Despite the general pessimism around, things are getting better

every day. Its $478 billion (Rs 22.94 lakh crore) GDP may rank a

distant twelfth, but it is the second-fastest growing among the

top economies. It may have the world's most poor, but every year

the country graduates an estimated five lakh engineering and technical

students-all potential global workforce. India's 56-year-old democracy,

despite its paralysing politics, is one of the strongest in the

world. Its consuming middle class of 300 million is bigger than

the UK, Germany, France and Italy combined.

That's not all. India has the highest arable

land in terms of land-to-size ratio, it is the second-largest producer

of fruits and vegetables, and it has the highest area under irrigation.

Of natural resources, the country has everything from iron ore to

gas. And over the last decade, the country has increasingly occupied

a greater share of world consciousness. Be it the recognition of

India's software talent, back-office operations, sourcing of manufactured

products, or merely Aamir Khan's blockbuster Lagaan. Nobody can

deny that India today is much stronger, a more forceful member of

the world economy than it ever has been since the eighteenth century.

There are more Indians than ever occupying important corporate,

academic, and research posts globally.

|

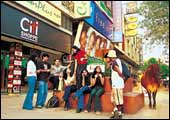

CONSUMERISM

Consumers throng Mumbai's Crossroads

India's middle class of 300 million

is bigger than the countries of the UK, Italy, and France combined.

Growing prosperity will make it one of the world's biggest markets

for everything from cereals to cars. |

|

And now at least one man thinks it is possible

to grow its $478 billion (Rs 22.94 lakh crore) GDP, which grew at

5.4 per cent last year, into a $9 trillion (Rs 4.32 lakh crore)

economic powerhouse by 2020. At FICCI's recent 75th AGM, the man,

Mukesh Ambani, Chairman and Managing Director, Reliance Industries,

spelt out how. "We can realise the vast untapped potential

of our people if we clearly identify the decisive parameters of

what we want to achieve," he told his audience.

Rays of Hope

It's easy to mock at Ambani's or anybody else's

vision of greatness for India. After all, the economy's ills are

so painfully obvious. Indian companies pay one of the highest rates

of interest. Power is not only expensive, but its supply is poor

and erratic. National highways are potholed and congested, and the

ports take forever to ship things out. Custom houses are dens of

greed, and bureaucracy both apathetic and corrupt. On an average,

labour is cheap, but its productivity-at least in the manufacturing

sector-is one of the lowest in the world. The good news: all these

issues are addressable, and some have been since the early 90s.

Says Amit Mitra, Secretary General, FICCI: "Just look at the

distance India has travelled since 1991."

|

MANUFACTURING

A chemical plant: Latent potential

Indian manufacturers may be at a

disadvantage in terms of capital cost and infrastructure, but

there is tremendous potential in labour-intensive industries,

whose exports-according to Accenture-could soar from $12 billon

to $57 billion by 2006. |

Indeed. Since then, the GDP has grown from Rs

6.93 lakh crore to Rs 22.94 lakh crore. Exports have zoomed from

Rs 44,000 crore to Rs 2,09,017 crore; foodgrain production has jumped

from 176.4 million tonnes to 211.3 million tonnes; poverty level

has gone down from 37 per cent in 1993-94 to 26 per cent today;

power generation, despite its troubled history, has increased to

113,000 mw from 74,700 mw in 1990-91; teledensity has quadrupled;

and the stockmarket capitalisation on the Bombay Stock Exchange

has risen to Rs 6,01,289 crore, from Rs 3,54,106 crore in 1991.

All that has been possible because 12 years

ago, India decided to end more than 40 years of economic isolation

and join the global mainstream by delicensing industries and inviting

foreign investment. That has helped Indian industry focus on improving

its own competitiveness rather than chasing licences and approvals

as it did until then. Therefore, more companies than before are

hiring consultants to deploy global best practices. Chambers of

commerce, especially CII and FICCI, are on an overdrive on a range

of issues-from plain networking within and outside to cluster development

to policy-level changes. Newer opportunities in the knowledge industry

have opened up-from BPO to engineering design to biotech. Says Surjit

Bhalla, MD, Oxus Investments: "I am very bullish about Indian

companies. Finally, they seem to have got their act together."

The Knowledge Economy

|

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

M.K. Dhir of Dhir Global Industria

A new breed of entrepreneurs in

both old and new economy is tapping top-of-the-line opportunities

globally. Dhir, for example, makes Hugo Boss suits at the only

facility of its kind in Gurgaon. |

|

If China, over the last 20 years, has established

itself as the factory to the world (it exported $266 billion, or

Rs 12,76,800 crore, of goods and services last year), then India

could become the back-office and laboratory to the world. Why? Because

of its human capital. According to Nasscom, some 19 million students

are enrolled every year in high schools and about 10 million in

graduate courses across India. Another 2.1 million graduates and

0.3 million graduates pass out of non-engineering colleges annually.

Even at current rates, Nasscom estimates, about 17 million potential

employees will be available for the IT industry alone by 2008.

More importantly, the shift in IT-related work

to India continues. According to research outfits such as Giga Group

and Forrester Research, the global slowdown and cost cutting will

increase outsourcing and offshoring in India's favour, although

there are new competitors on the market including China, Ireland

and Israel. A Nasscom-McKinsey report projects revenues from it

services and it-enabled services at $57 billion (Rs 2,73,600 crore)

by 2008, and employment at 4 million. At least two companies, Tata

Consultancy Services and Wipro, are near the $1-billion (Rs 4,800

crore) revenue mark. What's significant also is the value-added

work that Indian it players have begun focusing on. The tier-one

vendors, for example, are looking at business transformation work.

There are smaller companies such as Pramati Technologies, Moschip

Semiconductors and i-flex Solutions that have taken the product

development route, which will lend a face to the largely anonymous

work the industry does.

|

|

|

INFRASTRUCTURE

Golden quadrilateral (below) is a success story

India needs about $200 billion

to pull up its infrastructure to internationally acceptable

levels. The good news: Projects like the Golden Quadrilateral

prove that a quantum leap is possible.

|

|

Pharma and biotechnology are other industries

where India could become a global force. According to another McKinsey

estimate, the pharma industry has the potential to become $25 billion

(Rs 1,20,000 crore) big by 2010, and $100 billion (Rs 4,80,000 crore)

in 15 years thereafter. The opportunities lie not just in bulk drugs

and generics, but in research and development, especially in the

area of bioinformatics, genomics and proteomics, and data management.

Already, the Indian biotech industry is about $3 billion (Rs 14,400

crore) big, but most of the work is focused on low-end products

like vaccines and not the more value-added work in the areas of

proteomics or genomics. Bioinformatics, which marries the power

of computing to biotechnology, alone promises to be a $20-billion

(96,000 crore) global industry by 2005, and India could enjoy a

significant share of it.

A clutch of Indian companies, including Strand

Genomics, Avestha Gengraine, and Kshema Technologies, has hopped

on to the bioinformatics bandwagon, and by all indications they

are well positioned to win. India not only offers cheap qualified

manpower (according to some estimates, at one-third the global cost),

but also a wide array of research sample. Then, there are remote

service opportunities in contact centres and remote detailing. McKinsey

estimates that India can turn remote opportunities into a $275-million

(Rs 1,320 crore) business by 2010. Says Renuka Ramnath, CEO, ICICI

Ventures, which has invested in a bevy of Indian biotech companies:

"I think India has some clear advantages in this industry,

and we are very bullish about it."

That optimism could well be extended to the

pharma industry, where generic drugs are prying open lucrative global

markets. In fact, India's first multinational may well come from

this industry in the form of Ranbaxy Laboratories. But there are

other equally aggressive players here, including Dr Reddy's Labs

and Cipla, who are using their years of expertise in reverse engineering

to launch off-patent drugs, and even new molecules. The advantages

here are, again, costs and manpower.

|

|

|

TELECOMMUNICATIONS

India's new generation will be digital

The explosion in telecommunications

should hasten India's integration with the world markets,

and throw up new opportunities for remote work.

|

|

|

BRAND INDIA

The global Indians are now stuff of movies

Since the Nineties, India has occupied

a greater share of world consciousness and gradually the Made-In-India

tag is becoming more acceptable. |

Pay Dirt

At this point, the knowledge-based industries

may look more promising, but there is no reason to ignore the old

economy sectors of manufacturing and agriculture. Rather, the objective

should be to unlock the potential in both these sectors. And of

that, there's plenty. Take agriculture, for example. India has the

highest percentage of arable land, the highest area under irrigation,

is the world's largest producer of farm commodities, and the second-largest

producer of fruits and vegetables. The irony, however, is that it

is a marginal player in the world agri-trade, with 1.2 per cent

share of the $500-billion (Rs 24,00,000 crore) world trade. Similarly,

less than 2 per cent of the fruit and vegetable production is commercially

processed.

If India invests in cold chains, and helps farmers

with pre- and post-harvesting technologies, this wastage can be

turned into hard cash. Ambani of Reliance used a simple calculation

to drive home the potential. Israel, he pointed out, produces $4

billion (Rs 19,800 crore) of agri commodities on just 1 million

acres of land. By that measure, India's agri-sector could churn

out $1.9 trillion, or Rs 91,20,000 crore, (that's four times our

current GDP) in revenues. Fine, there are a number of issues relating

to pricing, distribution, and both tariff and non-tariff barriers.

But these can be resolved-if the government decides to.

A lot of people are beginning to write off

manufacturing. It would be a disaster to do so. For two reasons.

One, three-fourths of India's working population is still blue-collar,

and will continue to remain so in the short term. The services sector

does not have the potential to make up for whatever job losses a

reduced focus on manufacturing could lead to. Two, not all manufacturing

companies are globally uncompetitive. So what does it mean? That

it is possible for companies to make up for disadvantages in terms

of capital or infrastructure costs through process improvements.

Let us not forget that it took Japan more than 25 years to make

its mark globally, and China about 20. India has invested less than

10 years in putting its manufacturing house in order, and the short

learning curve of some of the companies could mean that they make

it to the world stage sooner than most expect. Besides, India does

not have to manufacture high-end products like semiconductors or

aeroplanes. It can do a damn good job of manufacturing CDs, footwear,

garments, chemicals, and components, and take shares away from existing

rivals. After all, government policies have little to do with things

like reducing quality defects or improving design. That's precisely

why not all companies in Japan are Toyotas or Sonys.

India enters the new millennium with a powerful

advantage on its side: the realisation that it can and must become

a global economic superpower. Still, should the first decades of

the millennium see India regress into global economic irrelevance,

it will be because it chose to. And not because it didn't have the

chance, or the wherewithal, to win.

|