|

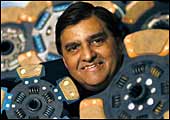

| Simplifying surgery: Ribbel's R.K. Kanoria

filed patent for a new surgical scalpel design |

| Ribbel's buyers asked the firm to patent

its new surgical scalpel design to pre-empt copycats |

On

December 13, 2003, Clutch Auto, a small manufacturer of auto components

in Delhi, faced a peculiar, but happy, situation. On that day, there

were pending buy orders for 2,10,616 of its shares on the Bombay

Stock Exchange, but no share was being offered for sale. The result:

the stock quickly soared to a 52-week high of Rs 21.80. A penny

stock catching the market wave? Hardly. Just the previous day, a

pink daily had published news of Clutch Auto receiving its first

US patent for a new clutch system that requires less foot pressure

to operate, which in turn reduces driver fatigue-a major cause of

road accidents in the US. Suddenly, an automotive industry minnow

with Rs 25 crore in annual sales had better prospects of breaking

into the $1-billion (Rs 4,600 crore) original equipment market (OEM)

for clutch systems.

Not too long ago, the story would have read

very differently. Either a company like Clutch Auto wouldn't have

bothered filing for a patent or investors would have merely yawned

at the news. Obviously now though, patent-protected innovations

like Clutch Auto's are being recognised for what they are: a cheque

waiting to be encashed. But how pervasive is the patent culture?

What are the industries that are more patent-friendly? Who are the

top patentees in the country? How many patents from India are being

filed in the US? Or what technologies are these patents trying to

protect?

Until recently, all these questions would have

drawn a blank, simply because there is no consolidated database

that readily answers these questions. Of course, you could have

obtained some numbers from the Indian Patent Office, but that would

not give you any idea of how many applications for patent are being

filed from India in the US. Besides, the Indian Patent Office takes

18 months or more to publish a patent for opposition after it is

filed, and six to seven years to grant a patent. So, any data is

bound to be dated. While BT can do little about the patent granting

procedures, it has done its bit to bring you the first ever survey

of patent trends in the country. Conducted in association with Evalueserve,

a New York-based IP research firm, the survey is a maiden attempt

at piecing together India's patent story. What did we discover?

Nothing less than a thriller in the making.

Here are some numbers from the BT-Evalueserve

Research survey: In 1997, Indian companies and/or Indian inventors

filed a mere 183 patents at the US patent office. Two years later,

the number had jumped to 285, and in 2001-the latest year for which

final numbers are available-it soared to 883. Assuming a modest

40 per cent rate of growth in patent filing, one could expect 1,200

patent applications from India for 2002 and a whopping 1,700 for

2003 (See The World of Indian Patents). As for the patent applications

received in India, the numbers-according to Delhi-based patent lawyer

Pravin Anand-have shot up to about 15,000 from 4,000 or so up until

1995. Another indication that the patent market is busier than ever

is the surge in the number of patent agents: 147 in 1992 and 514

this year. Says Anand, who has helped file more than 10,000 patents

in India and elsewhere: "Now there is no field where IP (intellectual

property) is not involved. People who think IP see IP in every step."

What are the industries that are on a patent

overdrive? While traditionally it used to be chemicals, the new

aggressors are electrical and electronics, and pharma (there is

some amount of overlap between chemicals and pharma). That's hardly

surprising. Two of the biggest growth stories in the past decade

have been it and pharmaceuticals. Besides, the two have been the

most affected by changes in India's own patent regime. While the

country has had a Patent Act since 1970, it only recognised process,

and not product, patent in food, drugs, pharma and agro-chemicals.

But after India signed the trips agreement in 1994, the rules of

the game started changing. And a third amendment to the Act was

tabled in the just-concluded winter session of Parliament, paving

the way for a product patent regime starting 2005.

|

| Flexing muscles: Facilities such as this

Mohali lab give Ranbaxy an edge in its race for patents |

| For the past few years, pharma companies

have been using patents to muscle into foreign majors' markets |

While pharmaceutical companies made the most

of the process patent regime by reverse engineering a new process

for an existing drug, the software industry faced a slightly different

situation. Unlike in the US, India's Patent Act does not cover software,

leaving it to seek protection under the copyright laws. Nevertheless,

software, being an industry where a lot of IP gets created, has

been a key driver of the intellectual property movement in India.

Says Prabhu Goel, Chairman, iPolicy Networks, a networking security

start-up that has 20-odd patents pending in the us patent office:

"To be successful in the marketplace, you have to make sure

that you are protected."

For the past few years, pharma companies have

been using patents to muscle their way onto the turf of foreign

majors. This usually involves developing a new manufacturing process

or a new drug delivery system to launch generic versions of blockbuster

drugs where the patent has expired (a patent is valid for 20 years).

The most recent example is Ranbaxy's challenge of Pfizer's anti-cholesterol

drug Lipitor, which has raked in $8 billion (Rs 36,800 crore) in

revenues. The decision in this case may take three to four years

to come. Although litigation costs in such a case can be as high

as $2 million (Rs 9.2 crore), companies like Ranbaxy don't shy away

from it, simply because if they win, their generic drugs can fetch

much more. Says Raghu Cidambi, Head (Corporate IP), Dr. Reddy's

Labs: "Patents are top of the mind for discovery-driven companies

like ours and Ranbaxy."

It's not just private sector companies that

are piling onto the patent bandwagon. Even once-sleepy government

labs are turning patent savvy (See Storm In A Beaker, page 154).

And right at the forefront, ahead of even Dr. Reddy's and Ranbaxy,

is the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. Ever since

R.A. Mashelkar took over as its Director General in 1995, he has

brought in a strong patent culture. These days CSIR scientists are

forbidden from publishing a research paper without actively considering

filing for a patent first. In doing that Mashelkar has corrected

a problem that had long plagued India's scientific community: technology

developed in the country would get patented by somebody else abroad.

Courtesy Mashelkar, CSIR has more than 600 patents filed for under

its belt. Says he: "It is important to find a way from Saraswati

(read knowledge) to Lakshmi (wealth)."

Guess what? Doing that isn't all that hard.

Why? Because patents are not so much a product of deep science as

good business. Most patents are granted for inventions that are

simple, incremental and that help in improving a technology or a

business model. For an invention to be patentable, it must be new,

non-obvious and useful, and nothing more. One example of a simple

invention is the popular Post-it(tm), a product of skunkworks at

the Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing (3M) Corporation. This

invention was conceived when a 3M employee wanted something that

would help mark the pages of his hymnbook. The Post-it(tm) design

and its uses prompted 3M to think innovatively and patent numerous

applications, including one for software applications that had a

user interface identical to Post-it(tm).

|

| Turning self-reliant: Clutch Auto's V.K.

Mehta turned to in-house R&D for innovation when MNCs set

stiff conditions |

| A Rs 4.5-crore loan, two British consultants

and ambition helped Clutch Auto jumpstart its research |

SpinBrush is another example that demonstrates

the patentability of simple inventions. It is an electric toothbrush

made by Procter & Gamble (P&G), but was invented by four

entrepreneurs from Cleveland, USA, who patented it. Later, they

sold the patents and its technology to P&G for a whopping sum

of $475 million (Rs 2,185 crore). Patents are also granted for simple

improvements or a modification of a known technology or an invention.

For example, there are more than 400 patents for different kinds

of paper clip, which was invented way back in 1867. Evalueserve

estimates that just the licensing value of these 400 paper clip

patents is over $80 million (Rs 368 crore).

India, because of the limited R&D budgets

that most companies have to work with, happens to be a natural breeding

ground for simple and incremental research. Just ask R.K. Kanoria

of Ribbel International, a Rs 5-crore surgical instruments company

located out of Old Delhi's congested Daryaganj. In April 2003, Ribbel

filed for a US patent for a new design of surgical scalpels. The

innovation increases the safety features of the scalpel and reduces

several health hazards that doctors and nurses are exposed to in

the operating theatre. Says Kanoria: "Our innovation is based

on the feedback from our buyers. They told us to patent the innovation

so that we could prevent others from copying our design."

For Clutch Auto, the motivation was the changing

rules of the technology game. About four years ago, the company

tried striking a joint venture with multinational clutch-makers

like Valeo and Sachs Mannesmann. But they put forward stiff conditions-a

minimum ownership of 51 per cent, no bank borrowings, no public

ownership, and disbanding of the current product line. "It

was too high a price to pay for their technology," says V.K.

Mehta, the company's Managing Director.

So Mehta decided to turn to his own R&D

for developing new products. He hired two British consultants, arranged

for a Rs 4.5-crore soft loan from the Department of Science and

Technology and aimed big. When Clutch had the innovation in place,

its team sifted through 11,000 patents filed since 1926 on clutch

cover assembly, just to make sure no patent was being infringed.

The patent was filed in February 2001 and it was granted in September

this year. Mehta has four more innovative products in the pipeline,

patents for which have already been filed over the last four months.

If more Mehtas and Kanorias think IP, you may

just have a country that makes up for its patents tardiness with

a vengeance.

-reporting by Sahad P.V.

|