|

| "In the next 10 years, there will be

dimensions of scale that will justify manufacturing, both by

Indian corporations and MNCs" |

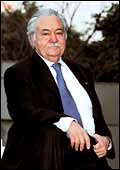

The

resemblance is striking. Pasquale

Pistorio, CEO of the Geneva-based $7.2-billion chipmaker

STMicrolectronics is a dead ringer for Vitalstatistix, the chief

of the Gaulish village we all know so well form the works of Messrs

Goscinny and Uderzo. That's only apt: within his industry, Pistorio

is a legend of sorts. The great microprocessor meltdown of the early

2000s left ST unscathed, thanks largely to Pistorio's decision (as

early as the 1990s) to focus on chips for devices and appliances,

not just computers. The 68-year-old was in India to inaugurate ST's

new development centre in Noida, a Delhi satellite. He spoke to

BT's R. Sukumar about India,

ST, and (listen carefully) the technologies he is betting on to

stimulate chip demand in the future. Excerpts:

You're an India regular. How many times

have you visited the country?

Many times; roughly, once a year. We opened

a liaison office in India in 1984, or 1985, and the software centre

in 1989. If I go back in time, I think what influenced my decision

was that India had the intellectual infrastructure to provide the

right talent to any position in the company.

The university system was excellent, the school

system was excellent, the legal system was very good, and the people

were educated. This was a big decision: so, in 1989, we started

hiring young (Indian) engineers and sending them for training to

Europe. From that point to now, we have 1,500 people. So, it's been

a pretty good and satisfying experience.

There were problems in the late 90s, when people

were leaving ST because there was a boom in software and everyone

was going to the US. We were becoming a kind of training base...but

again, the experience of all this was very good.

There is another reason for our presence in

India, and this is our philosophy. You get into a market for several

reasons: resources you wish to tap, access to the market of your

products, and economic conditions. In India, the resources are there,

the economic conditions are there, but the market for our products

is not there. I believe that in the next 10 years-and hopefully

in the next three to five years-we will see very fast growth in

the demand for our silicon because there is a fast-growing affluent

middle class and a strong demand for electronic appliances. There

will be the dimensions of scale in the market that will justify

manufacturing, both by Indian corporations and MNCs in India to

manufacture.

Why Noida, and why not Bangalore? When you

set up shop, the only other chip major here was Texas Instruments

and it was in Bangalore.

That's right and we were the next. We are now

opening a centre in Bangalore. But in 1989, Delhi, the capital,

was better in terms of infrastructure: (for instance) international

connections. Then, when the time came to put down our second centre,

we asked ourselves, 'Why not Bangalore?'. Then, we decided to stay

where we already were.

Now, with the presence of so many multinational

companies, Bangalore has become a very dynamic environment that

requires our presence. We are opening this office and we have rented

space for it. If things work out, we will go ahead and make a campus

there too, but so far we think this is a great place. There is also

another advantage here. The employee turnover in the Noida area

is much less. In our business, this is a big advantage.

You were speaking about the Indian market...What

kind of volumes would you need before you think of manufacturing

in India? Volumes are picking up in cellular phones, set top boxes...

I don't think it's only volumes. Our current

infrastructure, our locations of manufacturing, will serve us in

our plan of expansion for the next five years. So, for the next

five years, we do not perceive the need to look for other locations

for manufacturing operations. However, after then, we will see if

the volume pushover will be able to justify...I think the market

is going to grow 10-15 per cent a year worldwide; India will grow

double that. So this market will become very important. Our sales

here will grow very rapidly.

|

| "The market is going to grow 10-15 per cent

a year worldwide; India will grow double that. Our sales here

will grow very rapidly" |

How location specific do you need to be in

the chip industry?

For some products, very, for some, not at all.

There are certain basic products like memory. You can do memory

chips in Taiwan or Korea, and ship them all over the world. But

if you are making customised chips, then it is advantageous to be

close to the customer.

How closely do you work with contract manufacturers

like Flextronics?

Flextronics is a big customer. So is Solectron.

I've read in the press that Flextronics is considering a major manufacturing

presence in India. They see what we see, the growth of an affluent

middle class demanding electronic appliances and, therefore, there

is no need of importing, you can manufacture here.

If you allow me to be honest and frank, I think

the Indian environment is a bit difficult for manufacturing for

two reasons: the procedural or bureaucratic system is too slow for

the speed of our industry. And the other one is infrastructure.

Telecommunications is no longer a problem in India, but your airports

do not reflect a major manufacturing power.

ST didn't get affected when the microprocessor

industry went into a slump in the early 2000s because it had already

decided that it would focus on chips for appliances and cellular

phones in the early 1990s, a revolutionary strategy at a time when

everyone was looking at computers. I believe you invest around 10

per cent of your operating profit every year on researching future

technologies...

First, let me specify the number. The operating

profit is variable; so I will make it sales. We invest 0.5 per cent

of sales in research, non-product linked research. Companies that

plan to stay here in the long run must look into the future. We

spend $30-$40 million a year doing this; in research activities

that are associated with future revolutions like nanotechnology,

biotechnology, and MEMs.

A company has the obligation to serve the future.

We have engineers in the Berkeley; we have engineers in MIT, in

University of Melbourne, we have engineers in the most advanced

universities of Europe, and this is a window in the knowledge areas

that we spend some money. Not in isolation; we are working with

centres of knowledge at the most advanced universities of the world

to be sure we'll be catching it early enough. For example, this

so called system on chip, that has been the buzz word in the last

10 years; if I remember, in 1983, when we opened our design centre

in Germany, we were speaking publicly on the system solution on

silicon, well, the system wasn't there, but we knew this was the

way technology was progressing.

Name one emerging technology important from

ST's point of view.

One is MEMs, which is not so emerging; it is

emergent. When we started working on it, 10-12 years ago, it was

emerging. Now, it is coming into 'volumes'. Second one that is relatively

closer is biotechnology applied to biochip. Not having organic material

based transistors, but having biotechnology applied to silicon so

that we can have medical applications. In the next five years, you

are going to see a huge variety of biochips for medical applications,

DNA identification, lab on a chip. Third one, which is a bit remote,

but which has huge implications is nanotechnology.

Nanotechnology can create totally new materials.

To mention some of the things we are working on: we believe that

you can do solar panels using plastic dotted with nanocubes rather

than silicon. This way we can have photo-electric conversion at

the price of oil. If you can generate electricity at the price of

oil it will be fantastic. Then, there is photonics. We have invented

long ago, silicon emitting light, and using the light to connect

parts within the silicon, instead of using diodes. We see a huge

potential if the light can become the connecting material rather

than the wires, the speed will increase.

How important are the India operations to

ST?

Very important. Let me make some quantification.

If I look at the workforce of ST, it's about 44,000 people. Out

of those 44,000 people, there are 8,500 engineers. Out of that,

1,000, going on 1,500 are here. We are saying that over 10 per cent

of our R&D population is in India. In the next three to four

years, we will more than double this population in India, but we

will not more than double our overall engineering workforce. Because

you have very good engineers. At the output level, an Indian engineer

costs much less than an European engineer.

|