|

| The rolling hills of Munnar: KDHP's

participatory management model is unique in a state riddled

with labour unrest |

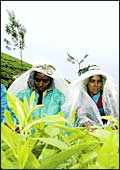

Muniswamy,

Sasikala, Ramalaxmi and Mahalaxmi are four shareholders of Kanan

Devan Hills Plantations Company (KDHP Co), a conglomeration of

17 tea estates scattered across 23,784 hectares of plantation

land on the green rolling hills of Munnar in Kerala. Like any

shareholder at any corporate entity, these four small investors

are part-owners of the private limited company they've invested

in, and stand to gain their respective share of profits generated,

via dividends.

Unlike most common shareholders, Muniswamy,

Sasikala, Ramalaxmi and Mahalaxmi have a representation on the

management and in the operations of KDHP Co, and can actually

contribute to decision-making.

Unlike most common shareholders, Muniswamy

and company are also employees of KDHP- they're just four of the

11,400-odd field workers who pluck away daily in the tea plantations

on Munnar's High Range, earning on an average a little over Rs

2,000 per month in wages (excluding a host of benefits like free

housing, free medical aid for family, bonus, gratuity and free

primary schooling).

|

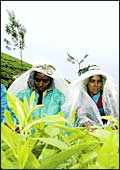

| Green fingers: Both worker and land

productivity have gone up |

Unlike most employees of India Inc., a little

over 97 per cent of the 12,000-strong workforce at KDHP-including

field workers, staff and management-have taken the gamble of their

lives; they are contributing 74 per cent of the Rs 13.5 crore

subscribed equity capital of KDHP Company Private Ltd, a tea-producing

business that showed a loss of Rs 9.6 crore last year, when it

was a division of Tata Tea.

Registered on March 15 and commencing operations

on April 1, following Tata Tea's decision to exit the losing plantations

business (Tata Tea now holds just 19 per cent of the equity),

each of these former Tata employees has on an average invested

Rs 3,280 for 328 shares of KDHP Co. Other than the field workers,

the employees include the 600-strong staff, like Management Assistants

S. Selvaraj and S. Gurudas, who take home a monthly salary of

Rs 7,000. An upbeat Selvaraj has mopped up 30,000 shares, risking

Rs 3 lakh in the collective endeavour to turn around the plantations'

business. The commitments get larger on the upper rungs of the

ladder at KDHP House, the registered office of the company. For

instance, 35-year-old Chaco P. Thomas, Head, Non-Tea Operations,

who's worked for 13 years at the Tata Tea plantations, has pitched

in with Rs 11 lakh. And then there's MD T.V. Alexander, probably

the biggest reason for the workers agreeing to this extraordinary

game plan: He's contributing Rs 20 lakh to the capital base of

KDHP Co.

|

"KDHP's model is

the best option for the workers. They get to keep their jobs

at a time when elsewhere tea gardens are closing down"

T. V. Alexander

Managing Director/ KDHP Company |

Welcome to arguably the world's most unique

model of participatory management, inimitable not just because

of its elements, but also because of its sheer audacity, the incredible

intensity of employee-commitment it elicits, and the high risk

it comes with- which is only lower than the levels of confidence

visible on the faces on Munnar's High Range. "Our hard work

will make a difference. We will get a return on the money we've

invested in the first year itself," says Sasikala in Tamil,

a field worker at the Chokanad factory on one of the estates (most

of the workers are fourth-generation Tamilians, since Munnar in

the pre-Independence era was accessible only from Tamil Nadu;

this prompted the British to make it mandatory for every planter

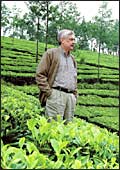

to learn the Tamil language). Adds Selvaraj: "It's the same

team (all ex-Tata Tea), only the sense of ownership is more now.

Our expectation is that in five years, Rs 10 will become Rs 100."

(The shares have a three-year lock-in, after which they can be

sold to other employees.)

That may well happen, but it won't be a breeze.

To be sure, the choice of the participatory management model wasn't

made because of the romantic or utopian connotations that come

along with it. Rather, in many ways it's the final roll of the

dice for KDHP, which operates in an industry that's buffeted by

oversupply, the lack of pricing power, as well as poor land and

labour productivity. "It's the best, and only, option for

the workers: They get to keep their jobs, and continue to get

the same benefits, at a time when tea gardens are closing down

one after the other," points out Alexander, a veteran of

over three decades at KDHP, even before the Tatas bought into

the plantations from its English owners in the mid-seventies.

The Tatas, for their part, had their strategic

reasons for exiting the plantations, which have run into losses

for four straight years, 2000 onwards. "The model of an integrated

tea company isn't right for us at a time when consumers are redefining

ingredient requirement almost on an overnight basis," reasons

Percy Siganporia, MD, Tata Tea. "If we have to grow our branded

business, we needed to find a solution to the plantations' business."

|

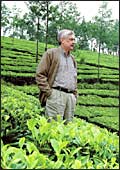

| Staff members, (from L to R) Nair, Gurudas,

Selvaraj and Abraham: The team is the same, only the sense

of ownership is more |

The most obvious solution would have been

an outright sale, but since the estates are sprawled over concessional

land, its value would be lower than that of freehold land (the

original deal for the estates dates back to 1877 when the Poonjar

chief gave a grant of 1.4 lakh acres to an Englishman for agricultural

purposes for a princely down payment of Rs 5,000 and an annual

fee of Rs 3,000). But as Alexander points out, for the Tatas,

two concerns larger than the valuation were the welfare of the

workers and the fragile eco-system. "We had our doubts whether

a new owner would have those priorities."

A second way out was a cooperative model,

but a three-month trial on one of the estates didn't work, with

productivity and quality both falling. Perhaps a combination of

desperation and ingenuity resulted in the workers themselves propounding

the participatory model. In February 2004, a small group was constituted

at KDHP to take this idea forward. When Siganporia visited Munnar,

the proposal of an employee buyout was thrown at him. The MD,

in turn, took the idea up to the board, to Director N.A. Soonawala

and Vice Chairman R.K. Krishna Kumar, who duly gave the go-ahead.

KDHP Co was on its way.

Even the unions are upbeat, which is nothing

short of miraculous in a state riddled with labour unrest and

in an industry notorious for striking workers. "I am happy

for three reasons: Continuous employment is guaranteed, the industry

survives, and employees can now look forward to returns,"

grins R. Kuppuswamy, President since 1956 of the INTUC-affiliated

South Indian Plantation Workers' Union.

|

| Field workers (R to L) Muniswamy, Sasikala,

Ramalaxmi and Mahalaxmi: They have bought over 300 shares

each and expect returns in the first year itself |

Workers, staff, management, unions-and even

the local politicians-exuding such optimism in the face of such

Herculean adversity could make you wonder whether it's one big

delusion (fuelled perhaps by the languid use of a particular weed

that sprouts liberally on Munnar turf). After all, here is a business

that's been reeling under losses for four years now-a business

that even the house of Tatas was unsuccessful at bringing to heel.

What's more, not much has changed since the Tatas drove out of

the High Range-the workers are the same, as is the management,

as is the dismal state of the tea plantations industry. Just how

is KDHP going to sail into the black, and dole out dividends to

employees even as it begins to wipe out its huge debt? The plantations

have been valued at Rs 68 crore, with icici Bank providing a primary

loan of Rs 25 crore and Tata Tea pitching in with a subordinated

loan of Rs 35 crore. (icici Bank has provided a first-year mortarium,

after which KDHP begins paying back at 8.5 per cent; the Tata

Tea loan payback begins between the 11th and 20th year; if cash

flows are strong, KDHP plans to begin paying Tata Tea back from

the fifth year, and if all goes according to business plan, KDHP

could be debt-free any year between the 12th and the 15th).

At the heart of the can-do mindset at KDHP

Co is the genuine belief of the worker that he is also an owner

of the fields he toils in. The commitment, too, is highly contagious.

Yet, the turnaround story isn't being scripted just by rushes

of emotion and adrenalin; there's some clear-cut common sense

strategy involved too. If, for instance, worker productivity is

up 58 per cent and land productivity up 28 per cent in the first

two months of the current financial year, it has as much to do

with the new-found sense of ownership as it has to do with a retirement

scheme that rightsized the organisation by 3,300-odd (a near-impossible

feat to pull off in unions'-dominated Kerala). What's also helping

boost the output is a new wage formula that's linked to productivity

and prices.

| CSR HERE IS AS OLD AS THE HILLS |

|

| Workers at Athulya: Community

welfare is a way of life here |

Recently the

Aranya natural dyes welfare unit, tucked away in Srishti Complex,

amidst the dense flora and foliage of KDHP's Nullantanni tea

estate, received a rather significant order: Four shirt lengths

of 2.5 metres each needed to be dyed using pomegranate and

indigo as raw material (available in plenty in the virgin

forest of Munnar). For the young, talented bunch of handicapped

workers at Aranya, every order is greeted with enthusiasm,

but this one was clearly special. It had come from one Ratan

Tata.

An order straight from the Chairman

of Tata Sons is doubtless the best indicator of the attention

the group showers on its workers. And that straight-from-the-heart

interest is reflected in adequate measure in Munnar at the

various vocational training centres within Srishti Complex.

Like the Development Activities & Rehabilitation Education

centre, where 65 students make 70,000 bottles of High Range

Strawberry Preserve annually, which Tata Tea markets nationwide.

Then there's Athulya, where 25 youngsters make stationery

that's supplied to the KDHP and Tata Tea. And there's also

a unit of the Tata Tea Wives' Welfare Association, comprising

employee wives, who make laundry bags for the Taj hotels

and spray-coats for the plantation workers.

The Tatas spend Rs 3 crore annually

on welfare in Munnar, with the referral hospital (there

are also 30 estate hospitals) accounting for Rs 2.4 crore

of expenses and the 497-student strong High Range School

running a Rs 90 lakh annual tab. With Tata Tea now just

a 19 per cent shareholder in KDHP Co, the onus is to make

each of these units self-sustainable-Tata Tea will continue

funding them till then-after which they could well begin

making meaningful contributions to KDHP Co. The 160-bed

general hospital, for instance, which provides free healthcare

and medication to employees, will attempt to generate income

by either starting a nursing school or foraying into medical

tourism or offering additional surgical procedures. But

in this quest for new revenue streams, the foremost priority

won't be lost: To cater to the community's needs. Self-sustainability

comes later. In Munnar, faddish buzzwords like CSR are indeed

as old as the hills.

|

With Tata Tea out of the picture, KDHP gets

a huge leg-up on the overheads front. "KDHP now doesn't have

to bear my cost, the cost of an expensive board or the cost of

our international operations," says Siganporia. That's how

overheads have come down by Rs 12-14 per kg of tea produced (KDHP

produces 21 million kg of tea annually). And that's one big reason

why Alexander is in a position to project a net profit of Rs 9.4

crore for the current year. In the April-May period, KDHP booked

a profit of Rs 2.95 crore.

However, if KDHP Co has to sustain profitability

in the years to come, it has to veer away from the vagaries of

the tea business (currently 50 per cent of revenues accrue from

low-margin auctions). Alexander talks about a foray into the loose

tea segment, but clearly KDHP's future rests squarely on a legislation

expected to be passed in the ongoing session of the Kerala Assembly,

which will allow plantations in Kerala to use 5 per cent of their

land for non-plantation activities. The KDHP top brass expects

this legislation to sail through soon enough, after which it can

move ahead with its various diversifications, which will be more

profitable than tea in three-to-five years (in the current year,

the non-tea activities are expected to contribute Rs 1.2 crore

to KDHP Co's profits). There's plantation tourism, with KDHP's

24 heritage bungalows (vacated by managers who opted for retirement)

translating into 70 rooms replete with an old-world feel (teak

and rose wood furniture for instance). Floriculture is a longer-gestation

business from which Alexander expects decent returns, as are horticulture

crops, winter vegetables and medicinal and aromatic plants, all

for which Munnar's climate is ideal.

Meantime, every attempt is being made to

squeeze revenues out of each operation of KDHP Co, be it the retail

outlet in Munnar or the Tea Museum, which boasts a scaled-down

version of the tea manufacturing process-a hot draw with tourists.

Also, the pace of revenue at the welfare units, still funded by

Tata Tea, is being stepped up, the medium-term objective being

to make them self-sustainable, and eventually contributors to

the KDHP Co P&L (see CSR Here Is As Old As The Hills). Alexander

isn't known to boast, and when he says "kdhp's operations

shouldn't be confined to Munnar," you want to hear more.

"We should look at acquisitions of plantations-which is our

core strength- even abroad," he suggests. He goes on to talk

about the possibility of taking KDHP public in three-to-four years,

thereby creating a broader market for its shares. Such ambitions

are still but a gleam in Alexander's eye, but it's doubtless a

sparkle that the 12,000 KDHP Co employees on the High Range have

little trouble aligning with.

|