|

| Getting paid for being green: SRF plant

in Bhiwadi (above) and SRF's CEO & President Roop Salotra

|

|

|

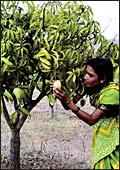

About

60 kilometres south-west of Bangalore, Anandi Sharan Meili keeps

a keen eye on the thousands of mango trees that are growing in

the farms of Gudibanda taluka of Kolar district. About four years

old, the mango trees are more than just that. In fact, they represent

the new face of a global trade that has sprung up around controlling

emission of greenhouse gases (GHG). The trees were planted by

local farmers but paid for by the British rock band Coldplay in

2002. Why are rockers, of all, planting trees in Karnataka? Here's

the story: When Coldplay got around to releasing its second album

A Rush of Blood to the Head that year, a UK firm by the name Future

Forests (now called The CarbonNeutral Company) got in touch with

the band's frontman Chris Martin (he's Gwyneth Paltrow's husband)

and asked him if he would like to do something about the carbon

emission that would be involved in production of CDs for the album.

Martin, as it turned out, said yes and for about $30,000 (Rs 13,50,000

now), agreed to fund planting of 10,000 mango saplings that would

grow to suck in carbon dioxide (co2) and release pure oxygen back

into the atmosphere (now you know why Future Forests renamed itself

CarbonNeutral). And Meili, who runs related NGOs in Karnataka,

was the one CarbonNeutral got in touch with for the tree planting.

(The British NGO also got Pink Floyd to do the same, but that's

another story.) What did the farmers get? Rs 10,000 per tree,

besides an annual supply of marketable mangoes for 30 years. A

remarkable example of how innovative business ideas are not just

helping save the environment but also enrich a poorer part of

the world. The good news? "Coldplay is not the best example

today. We have gone far beyond it," exclaims Meili, who runs

Carbon India and Women for Social Development.

She isn't exaggerating. From being individual

acts of guilt ablution, emission control has turned into a booming

and well-organised global trade. Thanks, of course, is due to

the Kyoto Protocol on climate control, which makes it mandatory

for signatory countries to meet their emission control targets.

Those that are unable to do so can simply buy carbon credits from

countries that help lower co2 emissions (See What Are Carbon Credits?)

to meet their targets. Some of the global buyers include energy

companies such as Shell Group, EDF, Solvay Fluor, banks such as

Barclays and specialised carbon funds of the World Bank and European

governments.

This has resulted in a spate of Indian companies

wanting to set up environmentally-friendly projects with an eye

on earning carbon credits. The list includes just about every

sort of organisation: private sector, public sector, cooperatives,

and even self-help groups. For instance, ONGC recently became

the first PSU to get an approval for carbon trading; Meili herself,

who's even got FIFA interested in a Green Goal initiative in the

run up to the World Cup Games in Germany, is helping 5,500 families

in Kolar build individual biogas plants of 2 cubic metres each;

and Shree Pandurang Sahakari Sakhar Karkhana, a cooperative sugar

mill, has also sought approval for carbon trading. Private sector

companies are, of course, way ahead in the game. Pioneering companies

such as Gujarat Fluorochemicals Ltd (GFL) and SRF have been joined

by big guns like Reliance Industries, Gujarat Ambuja, and JSW

Steel. Their collective sight is set on the at least $7.5-10 billion

(Rs 33,750 crore-45,000 crore) opportunity that emission trading

may throw up globally by 2012.

| WHAT ARE CARBON CREDITS? |

| These are certificates

issued to countries that help reduce greenhouse gases. The

US has had emission trade since the 1970s, but the concept

became popular with the Kyoto Protocol coming into force in

February last year. The protocol spells out individual emission

limits for member countries.

How does one earn carbon credits?

For every one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) reduced, the

country or the company gets one carbon credit. India at

present does not have any emission control targets, but

as a developing country it is entitled to earn carbon credits

in return for implementing "green" projects under

a clean development mechanism (CDM). Companies in developed

countries that have emission reduction targets till 2012

can partner with Indian firms through technology sharing

or financial help. Such green projects can then earn credits

for both partners.

Is certification required?

Yes, the green project must be validated by and registered

with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate

Control (UNFCCC), which also issues the carbon credits.

Where does one sell carbon credits and who buys them?

Currently, at least the CDM-related carbon credits or CERs

are not freely tradeable, but they can be privately placed.

However, carbon credits are expected to become freely tradeable

soon.

What's the going price for one carbon credit?

It ranges between m5 and m20, depending on the stage of

the approval process. For projects at pre-registration stage,

the price is lower. But those where credits have already

been issued command a premium.

How much can Indian companies earn from Carbon Credits?

At a very conservative estimate, $3 billion by 2010.

|

Green Bucks

Under the Kyoto Protocol, first adopted in

1997 but not ratified until February of 2005, there are three

broad methods of tackling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions: A joint

implementation mechanism is aimed at encouraging joint projects

among developed countries; carbon emissions trading allows countries

with surplus credits to sell the same to countries with quantified

reduction commitments, while clean development mechanism (CDM)

is about setting up projects that reduce GHG emissions in developing

countries. The CDM can either be in collaboration with project

promoters or done unilaterally by entities in the developing world.

Carbon credits so earned can then be sold.

CDM, which is the only mechanism available

to developing countries, has evoked a tremendous amount of interest

in India. In fact, the first project to seek the mandatory registration

with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC) under CDM in 2004 was an Indian project-GFL's project

for thermal oxidation of hfc23, a key waste produced in the manufacture

of refrigerant gas. Since then, several other Indian companies

have followed suit (See Companies With...). So much so that of

the 153 projects registered with the unfccc as on April 13, 2006,

28 are from India. "There are more than 500 CDM projects

in the pipeline over the next six months and we expect a third

of these projects to emanate from India," says Richard Kinley,

officer-in-charge of UNFCCC. The most popular CDM project types

include energy efficiency, renewable energy use, refinement in

industrial processes, switchover to cleaner fuels, and even solid

waste management. Says Deepak Asher, Group Head (Corporate Finance),

GFL: "CDM is a winwin for all concerned. The developed nations

are able to out-source environmental compliance cost-effectively,

developing nations get the advantage of technology, funding and

sustainable development, and most importantly, the environment

benefits by reductions in GHG emissions."

|

| Deepak Asher, Group

Head, Corporate Finance, GFL "CDM is a win-win

for all concerned" |

Advantage India

What explains India's first-mover advantage

on this front? "India already had stringent environment laws

in place for several years by the time the Kyoto Protocol came

into force," says Roop Salotra, President & CEO of SRF,

"so it was natural for India to be ahead of the pack in CDM

implementation." A couple of other factors seem to be helping

Indian corporates. Unlike those elsewhere, companies in India

were forced to keep their capacities small due to licensing and

restrictions. But when industry was deregulated in the early 90s

and companies scrambled to add capacities, they found that shifting

to newer and cleaner technologies was not just easier but more

viable. And now, high energy prices have ensured that energy efficiency

becomes the No. 1 concern across boardrooms in India. But most

of all, companies have discovered that going green and being able

to trade in carbon credits can actually boost profitability of

their new projects.

|

| M.K. Singhi, Executive

Director, Shree Cements "With carbon revenues,

the IRR (internal rate of return) is enhanced upto 30 per

cent, and we are looking at about 150,000 credits annually

from three different projects" |

Consider Triveni Engineering and Industries,

which has set up two bagasse-based power plants that will get

UNFCCC approval anytime now. The company estimates that these

plants will generate 160,000-200,000 certified emission reductions

(CERs), or carbon credits, annually. Even assuming a sale price

of m15, or Rs 825, per CER (every one tonne of co2 reduced fetches

one CER), the plants will fetch at least m2.4 million annually.

"We are looking at annual revenues of around Rs 16 crore

from the two plants alone," says the company's Vice President

of corporate planning, Sameer Sinha. No wonder, Triveni is setting

up a third plant by September 2006. Although Sinha is wary of

giving out investment figures for the projects, he does say that

carbon credits improve the viability of their projects. "They

can boost the internal rate of return for such projects by 3-4

per cent," he says. Rajasthan-based Shree Cements' Executive

Director, M.K. Singhi, agrees with the assessment. "With

carbon revenues, the IRR is enhanced by up to 30 per cent,' he

reveals. Shree has three projects in the pipeline that could qualify

for carbon credits. It is looking at generating 100,000 CERs every

year from its first two projects and expects to pocket around

Rs 10 crore from its first CDM project alone. Another project

related to waste-heat-recovery-based power generation is expected

to yield 50,000 CERs.

But the best example of the CDM potential

is SRF. This chemicals company took a call in July 2004 (seven

months before the Kyoto Protocol was ratified) to invest Rs 12

crore in building a plant to reduce emissions of hfc23. Its oxidation

plant was commissioned end of August 2005 and started generating

CERs rightaway. In March this year, SRF booked a business income

of Rs 95 crore from the sale of 1.4 million CERs-that's 144 per

cent of SRF's annualised net profit for 2005-06. And SRF has an

annual capacity to generate a maximum of 3.8 million CERs. For

companies like SRF and GFL, which have refrigeration gas businesses,

CDM projects make even more sense. HFC23, a byproduct, is one

of the most potent greenhouse gases and destruction of one tonne

of hfc23 is equivalent to reduction in emission by 11,700 tonnes

of CO2. GFL is looking at a best-case estimate of 7 million CERs

per annum, which means between GFL and SRF alone, there will be

about 10 million CERs generated annually.

| COMPANIES WITH CARBON CREDIT TRADING PLANS |

GFL

GREEN PROJECT: Destruction of waste product

HFC23 through incineration. HFC23 is a potent greenhouse gas

that is formed during the manufacture of refrigerant HCFC22.

One tonne of HFC23 has warming potential of 11,700 tonnes

of CO2.

TECHNOLOGY: Installation of thermal oxidation equipment

via technology partner UK-based Ineos Technology.

PROJECT STATUS: CER registration done

SCALE OF EMISSION: 33.9 lakh CERs, or carbon credits

EXPECTED ANNUAL INFLOW: Rs 88.1 crore

|

|

SRF PLANT IN BHIWADI

|

SRF

GREEN PROJECT: Thermal oxidation of HFC23.

TECHNOLOGY: Thermal oxidation (technology vendor

is Solvay Fluor)

PROJECT STATUS: Approved. Has already sold some

CERs that accrued during 2005-06.

SCALE OF EMISSION: 38 lakh CERs a year.

EXPECTED ANNUAL INFLOW: In excess of Rs 95 crore.

SHREE CEMENTS

GREEN PROJECT: Three projects, actually, involving

biofuels for pyro-processing in cement plant; Reduction

in clinker content by increased fly ash content; waste heat

recovery based power plant.

TECHNOLOGY: Developed largely in-house

PROJECT STATUS: At various stages, but the biomass

one is already registered.

SCALE OF EMISSION: 1 lakh CERs per year.

EXPECTED ANNUAL INFLOW: Rs 10 crore per annum

TRIVENI ENGINEERING

GREEN PROJECT: Bagasse-based power generation plants.

TECHNOLOGY: Developed largely in-house

PROJECT STATUS: Validation Stage

SCALE OF EMISSION: 160,000-200,000 CERs.

EXPECTED ANNUAL INFLOW: Has been revised upwards

from Rs 4.2 crore to Rs 16 crore

BALRAMPUR CHINI

GREEN PROJECT: Bagasse-based power generation plants.

TECHNOLOGY: Developed largely in-house

PROJECT STATUS: Validation process is currently

on, but Balrampur has sold a small fraction of its CERs

to IFC.

SCALE OF EMISSION: 1.8 lakh CERs.

EXPECTED ANNUAL INFLOW: Around Rs 5 crore.

Source: Sharekhan, BT

|

Market Dynamics

The overall size of the market in terms of

the number of co2 equivalents that need to be reduced during the

first commitment period of 2008-2012 is fairly capped at around

1.5-2.0 billion, according to Sameer Singh, IFC's environmental

and social specialist for South Asia. However, the CER prices

show no signs of being capped. "The benefits are likely to

be in excess of $3 billion (Rs 13,500 crore) over 10 years from

the 200-odd projects already approved," says Naresh Dayal,

Additional Secretary, Union Ministry of Environment and Forest.

The ministry's estimates are based on extremely conservative prices

of $5-6 per CER, which is far lower than the prevailing market

prices. Last year, the price of a CER was between m11 and 15.

This year already some companies are sewing up deals at over m20

for a CER. "By next year, the price could easily be m30 per

CER," says Meili of Carbon India.

|

| Triveni plant, Deoband

As per its own estimates, CERs could fetch the company

as much as Rs 16 crore a year |

A close surrogate of the CER is the carbon

reduction unit prevalent in the European Union, and that is currently

trading at m30. However, higher risk perception associated with

developing economies results in the CERs trading at a discount.

The formation of an international transaction log (ITL) by April

2007 is expected to remove such discrepancies. The absence of

ITL, for example, prevents Shell, SRF's partner in the DMD project,

to cash in on its share of carbon credits. "The absence of

an international transaction log is one the key factors determining

CER prices at present," notes Sudipta Das, Partner (Environment

& Sustainability Sevices), Ernst&Young.

There Are Risks, Though

While carbon trading promises almost free

money and lots of it, there are some risks involved in the mechanism.

Part of the uncertainty in the market is due to the US, the largest

producer of GHG, which hasn't yet ratified the Kyoto Protocol

and doesn't seem to plan on doing it either. There's also some

uncertainty as to what will happen after the first phase of commitment

gets over in 2012. Going forward, "the demand-supply equation

in the carbon market is going to be dictated by politics and policy,"

says GFL's Asher. GFL is trying to hedge by entering into forward

contracts for part of its annual CER production, and indexed prices

for yet another part of its portfolio. It will retain the balance

for the spot market, thereby keeping a small window open for potential

increases in CER prices.

|

| Anandi Sharan Meili, Carbon

India "There are a number of renewable energy

programmes that we are implementing as fully CER-funded projects" |

|

|

In CDM projects where technology partners

from developed countries are involved, the credits are usually

shared in proportion to the risks shared. Several projects, such

as Meili's biogas initiative in Kolar, however, are now planning

to take on the entire risk themselves as they see merit in retaining

CERs for trading later. Happily for her, these are risks that

financiers are willing to share as is evident from ICICI Bank's

advance funding of the biogas project. In a bid to encourage more

CDM projects, intermediaries such as the World Bank and other

specialised carbon funds chip in at early stages (mostly pre-registration)

by taking over substantial risk. Of course, such funds then end

up with CERs at significant discount to market rates.

There are other efforts on to make carbon

trading easier. IFC, for instance, is working on sophisticated

financial instruments such as carbon futures, indexed pricing

and carbon insurance. In fact, the first session of an Ad Hoc

Working Group on post-2012 commitments is slated for May in Bonn,

Germany. It is expected to clarify many of these grey areas. Dayal

of the Ministry of Forest and Environment believes that a relaxatio

n in the pace of commitments for the US might make the Protocol

more palatable to it.

UNFCCC's Kinley agrees, albeit a little obliquely.

"Longer commitment periods may make the agreements more interesting

for certain countries," he says diplomatically.

If the US agrees to ratify the Kyoto Protocol,

the carbon trading market may simply explode. Going green for

India Inc., then, won't just make a lot of sense, but also truckloads

of money.

|