|

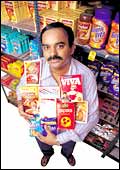

| Ramaswami Subramanian, Managing

Director, Subhiksha Trading Services |

For

the last two weeks, R. Ratnakumar has followed an amusing routine.

Every morning, he gets up at four and hops into his car to reach

Chennai's Koyambedu-a congested wholesale market for fruits and

vegetables-by half past four. Over the next three-and-a-half hours,

Ratnakumar skillfully negotiates (haggles, actually) the price and

quantity of the two dozen different fruits and vegetables he buys

every day. It's a war of nerves and bluster, and Ratnakumar must

stay his ground to get the best deal, not just in terms of price,

but quality (Koyambedu dealers can cheat, and if you've ever taken

an autorickshaw in Chennai, you know what we are talking about).

Ratnakumar could have been your average neighbourhood

fruit store owner, except that he's in reality a manager (legal)

at the Chennai-headquartered discount retailer Subhiksha Trading

Services, and currently in charge of a "special project".

Before Ratnakumar graduated to striking deals, though, his 37-year-old

boss Ramaswami Subramanian had him do the routine for several days,

where he would only watch Koyambedu's frenetic wee-hour trading,

taking in the peculiar lingo, learning how the various fruit cartels

in the market operate, how other big buyers such as Pazhamudhir

Cholai (a fruits-only retailer) negotiate, and how to tell, say,

a Malta orange from other oranges.

If the 38-year-old puts himself through the

gruelling routine gleefully, it's because of his employer. Subramanian,

you see, has always been unconventional in his methods. In 1996,

when he gave software the go by and turned his attention to retail,

after having dabbled in financial services, the typical thing to

do would have been to pick up an existing retail model-something

like a departmental store-and run with it. Subramanian, son of a

central banker, did no such thing. Instead, he worked backwards

from the market. His initial groundwork had yielded some interesting

insights into the workings of the retail industry. It seemed that

globally, the No. 1 retailer made most of the money; the No. 2 managed

to get by, but the others had to eventually down the shutters.

In Chennai, a market traditionally more receptive

to organised retail, there were some 15,000 kirana stores, besides

RPG Group's FoodWorld. Surviving in between the two categories of

retailers needed some out-of-the-box thinking. After some more research

and analysis, the IIM-A grad of 1989, zeroed in on a discount store

format that, as it emerged, is uniquely Indian. With Rs 5 crore

in capital from promoting company Vishwapriya Financial Services,

Subramanian launched Subhiksha, with a simple proposition: It would

sell everything at a discount (of 5 to 17 per cent) to the mrp.

Today, the chain has 139 stores in Chennai and some other cities

of Tamil Nadu, 1,000 employees, and by the end of this fiscal will

have Rs 230 crore in revenues and Rs 5 crore in net profits. All

created by a short, unassuming man with a razor-sharp mind (at B-school

he was reverentially nicknamed thalaivar, which is Tamil for Chief,

for perennially topping the class).

|

BIO-SKETCH

|

|

Ramaswami Subramanian

BORN:

June 2, 1966

EDUCATION: IIT Madras,

1986; IIM Ahmedabad, 1989

IDOL: Sam Walton

BUSINESS SLOGAN: Life-time

value for consumers

CAR: Mitsubishi Lancer

HIS LAST HOLIDAY: To Thailand

in March 2003 lasted three days

LIFE'S AMBITION: To be

remembered as the man who changed "consumers' perspective

on retail"

WORST NIGHTMARE: The death

of MRP (there are lobbies working towards this)

MARRIED TO: Sri Vidhya,

a qualified chartered accountant, cost accountant, a company

secretary, and a housewife

|

SPOTTING A NICHE

A big part of the reason why Subra-manian has

done much better than what his critics expected is Subhiksha's (Sanskrit

for prosperous) unique hybrid model. It is one that has the systems,

processes, and clout of a big organised retail chain, but the no-frills

convenience and access of a neighbourhood store. The choice of positioning

has meant that Subhiksha caters to the middle class, both upper

and lower. Therefore, the model has been configured in such a way

that it drives costs out of the system in every area of its activity.

Consider how Subramanian, an IIT Madras alumnus,

has achieved that. For starters, Subhiksha stores are bare bones.

Their size ranges between 1,500 and 2,000 sq ft, they have no air-conditioning,

no fancy lighting, and no attractive display. In fact, customers

can't even touch and feel the product they want to buy. Subramanian's

argument: What Subhiksha sells is not fashion but grocery and food

items such as rice and detergents, which do not require touch and

feel. The closest that Subhiksha shoppers get to a touch-and-feel

experience is at a model store in Tambaram, where a wall-to-wall

display shelf stocks samples of each product sold in the store.

The samples have a label each stuck underneath to the shelf, and

the customers must note down the item code number on the order form

they are given upon entering the store. A counter help takes the

form, picks out the ordered products from shelves behind the counter,

and delivers them along with the bill for payment. The only other

retailer who follows a system similar to this is the government-owned

Central Supplies Department (CSD). Subramanian explains his unorthodox

methods: "Unlike other players, Subhiksha has built up consumer

expectations and we must ensure that we are the cheapest."

|

| SHE'S HOT & HOW |

| For turning conventional retail wisdom

on its head with a made-for-India format

For getting consumers hooked to the concept of no-frills,

no-touch discount shopping

For proving his critics wrong by actually making profits

with a contrarian model

|

The supply chain is geared to deliver on this

philosophy. Most of the products are sourced directly from the producer

or manufacturer. For instance, rice is bought from mills in Raichur,

pepper from Wynad, and cardamom from Ooty. All products are purchased

on cash to squeeze out the maximum discount possible, and stock

keeping units (SKUs, or the products in the store) are restricted

to the fastest moving ones of about 1,500. A supply chain software

keeps track of inventory, and a fleet of trucks does milk runs from

the warehouses to keep the stores well stocked.

Daily innovations are things that improve processes

and add to wafer-thin margins. Take distribution, for example. Until

a few months ago, about 18 trucks used to leave the central warehouse

in Chennai at seven in the morning to supply to all the 70 stores

in the city, and return by three in the afternoon. Thereafter, the

vehicles would have nothing else to do. Nowadays, a staggered delivery

system and better route planning have allowed Subhiksha to reduce

the fleet size to 11 and ply it longer.

Similarly, when it emerged that order fulfilment

was taking more time than it should, Subramanian and his team came

up with a simple solution. They simply transplanted the stock management

system from their pharmaceutical department, where shelves and SKUs

are coded uniformly and SKUs stored in categorised bins to reflect

the way warehouse stored its own stock. The results were immediate:

The staff did not have to waste any time looking for products, besides

which stock-out situations were minimised. Says Subramanian, who

did a two-week stint at Citibank after IIM, before joining his mentor

(late) S. Vishwanathan at the ailing Enfield Industries to help

him turn it around: "What we learnt is that the whole process

should have a factory-like sameness and efficiency."

Entrepreneurial Passion

Despite Subhiksha's growth, the chain is pretty

much a one-man show. Subramanian, because of his obsession with

getting things right, is hands on in all areas of the business.

Part of it is actually unavoidable. For two reasons. One, retail

is a nascent industry and not too much of ready-made talent is available

in the market. Two, given the modest margins with which Subhiksha

operates, it would be unviable to rope in expensive top-notch talent,

which may or may not fit in with the chain's austere style of functioning.

Ergo, Subramanian's strictly regimented day

at work begins early and winds up late in the evening. He is usually

up at half-past five in the morning and begins by reviewing the

previous day's work and drawing up an "action plan" for

the day ahead. Between half-past six and quarter-past seven, he

speed reads at least eight newspapers, including two regional dailies.

By quarter-past eight, after a few minutes of prayer, he is off

to work in his black Mitsubishi Lancer, where he invariably eats

his breakfast of idlis or cornflakes.

Although none of his working days is typical,

it is long and hectic just the same. Subramanian makes it a point

to visit each of the 70 shops in Chennai at least once a month,

and those outside once every six months. Earlier, visits to the

warehouses used to take eight hours out of his weekly work schedule,

but now that's been cut down to four. All important decisions-which

could range from changes in SKUs to store location to supplier agreements-are

made by Subramanian. He's also the point man for investors in Subhiksha,

including ICICI Ventures, which owns a 10 per cent stake in the

company.

|

| Despite Subhiksha's growth, the chain is pretty

much a one-man show. Subramanian is totally hands on |

While recruitment of store staff is done by

an external agency, Subramanian insists on personally interviewing

managerial hires. He's even set aside a fixed time for the interviews:

6:30 pm to 9:00 pm. There's a set of qualities that he looks for

in each category of his employees. For example, the chief manager

is expected to have team management expertise and an ability to

think on his feet. The manager must pack boundless energy to carry

out daily duties and interface with customers. At the end of the

first three months, the new manager's performance is reviewed. The

way Subramanian does it is to sit with the concerned manager and

do a man-on-man appraisal. The decision to stay or leave, then,

becomes mutual. Still, the longest he is able to retain a manager

is 15 months. "It's the attitude that matters, I don't lay

any emphasis on book learning or marks," says Subramanian.

The store staff is hired

from areas nearby and is trained for 20-25 days in three or four

phases. Once in every five days they are tested for speed and productivity-how

long does it take for them to gather and bill 10 items. Until a

year ago, the attrition rate used to be a high of 25 per cent, but

now is down to 10 per cent, partly because of an increase in entry-level

salaries. A front-end employee with a high-school certificate starts

off on Rs 3,000 a month, with provident fund and other benefits.

Of the 1,000-odd employees, only a quarter are on Subhiksha's own

payrolls.

Over the years, Subramanian has put in a management

structure that despite some selective weaknesses has supported the

quick growth. Broadly, there are two teams: The backoffice team

looks after centralised operations such as accounting, warehousing

and it, while the front-end team manages the stores. There's a manager

for every three stores who reports to a chief manager for business

development who in turn reports to a vice president. The VPs-there

are five of them-are responsible for the sales targets and answerable

only to Subramanian.

EVOLVING BUSINESS

But as Subhiksha embarks on phase two of its

growth, which involves going to newer locations such as Mumbai and

Delhi, Subramanian will need a much more robust structure, which

at the same time must be flexible enough to adapt to local needs.

No doubt, the man knows as much. He first thought of growing out

of Tamil Nadu two years ago, but refrained from making the move

because of his unfamiliarity with markets outside. Even in Tamil

Nadu, Subhiksha made mistakes, but fixed them as it went along.

But a new market may be less forgiving of supply problems or order

fulfilment delays (FoodWorld ran into severe problems after it opened

in Pune, and it took a long time to sort them out). Therefore, Subramanian

had to perfect the existing system as much as possible before exporting

it to, say, Mumbai.

|

| Subramanian's ambition is to be remembered

as one who changed the Indian consumer's perspective on retail |

Having established the chain in Tamil Nadu,

Subramanian is trying out new things with the discount store format.

Ratnakumar's early morning trips to Koyambedu are part of a pilot

project that Subramanian has started in Chennai, and that is of

vending fresh fruits. The case for it is compelling enough. Subhiksha

has 1.5 lakh customers, and if each of them bought fruits worth

Rs 200 a month, it would mean Rs 36 crore in additional revenues

a year. But it wasn't the first time that Subhiksha tried its hand

at selling produce. Its earlier attempt to sell vegetables failed

because the losses from wastage exceeded the profits it earned on

them. Subramanian didn't give up, and decided to try fruits instead

because of their longer shelf life. He also decided to understand

the market dynamics thoroughly before making another attempt. Which

is why Ratnakumar had to make "dry runs" to Koyambedu

the first several days.

A growing customer base has prompted Subramanian

to add newer lines to the chain's departments. One is 350 new SKUs

of branded goods where no discount is available, but have been added

because of customer demand. Another is a direct-to-home supplies

of medicines. To kickstart the experiment, a field force was sent

out to each of the existing customer households to understand their

medicinal requirements. Currently, Subhiksha's representatives are

in the process of convincing its grocery shoppers to also buy medicines.

One thing that the chain has going for it is

the discount it offers on medicines. Drug stores generally have

a margin of 17-20 per cent, but Subramanian is willing to do with

7 per cent and pass on the rest to his customers. The interesting

bit: Even at this level, the percentage margins are double that

of grocery and more than 10 times that of fruit. The business is

tricky, though. So far in Chennai, anybody who tried selling medicines

at a discount-like True Values, which lasted but a year-has had

to shut shop. Subramanian is hoping Subhiksha won't meet the same

fate.

To be sure, there's a long haul ahead of him.

His self-admitted ambition is to be remembered as a man who changed

the Indian consumer's perspective on retail. So far he's played

his cards carefully. Watching his expenses, choosing locations carefully,

managing suppliers and customers with an earthiness that's typical

of a southerner. The ballgame now is vastly different: He's talking

of 2,000 stores across the country in another eight years. That

would mean revenues of Rs 6,000 crore, making him the undisputed

discount chain warrior. Could things go wrong? Certainly. But one

thing is for sure: One way or another, Subramanian is an entrepreneur

to watch.

|