|

Clearly,

pink is in. in the teeming crowd around me, I spot pink dresses,

pink ribbons and hair bands, pink lipstick, even pink sandals. Bright

lemon yellow isn't far behind, in terms of incidence, but pink is

clearly ahead. The thought crosses my mind that if there's a US

spy satellite capturing images of this part of New Delhi the result

will probably be a sea of pink. This part of New Delhi is an area

encompassing the South Delhi boroughs of South Extension and Defence

Colony. The overpass that is meant to streamline the flow of traffic

is clogged. The giggling mass of pink (and yellow) has spilled off

the pavement, narrowing the width of road available for motorists.

One driver rests on his horn, another gawks at a pink dress, and

still another leans out of the window and addresses a lewd remark

at a yellow dress. The women themselves are oblivious to everything.

Dressed in their Sunday best-not surprising since it is a Sunday-these

tribals-turned-Christians from Jharkhand are here to attend mass,

meet friends and lovers, and generally have a good time before they

head back to their mundane lives as ayahs, nannies, cooks, maids,

and housekeepers. Clearly,

pink is in. in the teeming crowd around me, I spot pink dresses,

pink ribbons and hair bands, pink lipstick, even pink sandals. Bright

lemon yellow isn't far behind, in terms of incidence, but pink is

clearly ahead. The thought crosses my mind that if there's a US

spy satellite capturing images of this part of New Delhi the result

will probably be a sea of pink. This part of New Delhi is an area

encompassing the South Delhi boroughs of South Extension and Defence

Colony. The overpass that is meant to streamline the flow of traffic

is clogged. The giggling mass of pink (and yellow) has spilled off

the pavement, narrowing the width of road available for motorists.

One driver rests on his horn, another gawks at a pink dress, and

still another leans out of the window and addresses a lewd remark

at a yellow dress. The women themselves are oblivious to everything.

Dressed in their Sunday best-not surprising since it is a Sunday-these

tribals-turned-Christians from Jharkhand are here to attend mass,

meet friends and lovers, and generally have a good time before they

head back to their mundane lives as ayahs, nannies, cooks, maids,

and housekeepers.

A few days later, and some 1,330 kilometres

away, I find myself in a region where the chances of encountering

a Mercedes SLK convertible and an unmarried girl in her twenties

are approximately the same. This is Simdega, a district in Jharkhand

that has witnessed an exodus of the species. Two days here and I

have already learnt how to identify families that have a Girl in

Delhi (GID) from those that don't. All houses in tribal areas-much

of the state's 79,714 square kilometers is classified thus-are mud

and brick ones with red burnt-mud tiles. The last are relatively

expensive, around Rs 1,200 for a lot of 1,000, and roofing a decent-sized

abode could cost anything between Rs 40,000 and Rs 50,000. GID families

live in house that are new or, at the least, have spanking new roofs.

They also have motorised pumps that draw water, and they rear pigs.

That's right, pigs: piglets can be had for as low as Rs 200, and

if fattened up well, a process that takes a couple of months, never

mind what the Earl of Emsworth has to say on the subject, can be

sold for Rs 2,000. Roofs, pumps and pigs seem to be the three common

accompaniments to having a girl in Delhi.

|

| Former maid Hana Tirkey (right) is picking

up the nuances of tailoring. She hopes to start a tailoring

institute with her earnings |

The phenomenon of Jharkhand's young women leaving

home and hearth for an uncomfortable existence in New Delhi-the

capital is the most attractive market for these women; Mumbai doesn't

pay as well; and Chennai and Bangalore are simply too far away-is

largely about economics. A housekeeper in Delhi may help put her

siblings through college, build a proper house for the family (red

burnt-mud tiles and all), and extend her munificence to gifts of

the porcine variety. Estimates from placement agencies and the church

suggest that there are around 35,000 to 40,000 women from Jharkhand

in Delhi earning, on an average, around Rs 2,500-Rs 3,000 a month-salaries

begin at Rs 1,500 and could go as high as Rs 5,000-and sending the

bulk of the money (around 50-75 per cent) back home or, as is the

preferred custom, carrying it with them when they go back home for

Christmas. In number-terms that translates into anything between

Rs 52 crore and Rs 126 crore, a substantial amount of money in a

state where 60 per cent of the population of 27 million lives below

the poverty line and the per capita annual income is Rs 4,161.

A Service Economy

Jharkhand's nanny revolution has been engendered

by a combination of factors: topography, economic development (rather,

the lack of it), the church, and the common malaise of indolence

that seems to affect the male of the species from Andalusia to the

Andamans. The Mundas, Kharias, Oraon, and Ho, the main tribes of

Jharkhand aren't exactly landless. However, the state's poor irrigation

infrastructure leaves these cultivators at the mercy of India's

mercurial monsoon. In a good year, these tribes can hope for one

good crop; the land is left fallow for the rest of the year, although

some tribals grow vegetables; these are watered from their private

wells and this is where the pumps fit in. Jharkhand isn't exactly

an industrial hotbed either, although the state does boast a profusion

of mineral resources. Santosh Kumar, the head of SPG Manpower Consultants,

a Delhi-based firm that recruits women from Jharkhand for employment

as maids, nannies, and cooks in Delhi, was appalled by the poverty

he saw on his first trip to the state. ''I decided never to go there

again,'' he says.

The tribes are matriarchal societies; women

call the shots and some men take the names of their wives post marriage.

Most men are drones and fritter away their time playing cards or

drinking haria, a local brew. Even the exodus to Delhi hasn't changed

anything: I see women toiling away in their small vegetable gardens

and men wandering around in search of liquor and idle companionship.

Then, there's the church. The first mission

was established in Jharkhand way back in 1845. Today, a significant

proportion of the state's tribals are Christians. Every village

boasts its own parish; attendance at Sunday mass and assorted 'moral

values' lectures is mandatory, and the Catholic nuns and priests

who run missions teach parishoners practical lessons related to

personal hygiene. Cardinal Toppo the Archbishop of Ranchi (Jharkhand's

capital) Diocese explains that the church also serves as a support

system, keeping an eye on the elderly parents or young children

of the women who work in Delhi. And the missions run primary schools

that educate tribals. The result is an army of women with great

work ethic. ''Of all the women who come to Delhi, the most preferred

are the ones from Jharkhand,''says Jaya Jha, Head, Kumar Peronnel

Bureau.

|

| A motorised water pump is an ubiquitous sight

outside houses owned by families with a 'girl in Delhi'. Jharkhand

is as parched as it gets |

A 'Girl In Delhi'

Sadhanu Bhagat is visibly perturbed. The Labour

Minister of Jharkhand would like to see the state's women stay where

they are. To that effect he has made it mandatory for every woman

(or, for that matter, man) leaving the state to go work elsewhere

to register herself and obtain an identity card from the state.

And he has conducted a survey of 14 of the 22 districts that make

up Jharkhand to ''target the migrating population in an effort to

provide local jobs and opportunities''. Posses of police personnel

at railway and bus stations have been ordered to watch for groups

of young women, and detain them; a move that is explained away as

something aimed at preventing human trafficking, although its real

motivation is something far more sinister and anti-free market-preventing

migration.

Like most such measures, however, this one

is an abysmal failure. Young women who make it to Delhi and earn

a living as a cook or nanny become role models for other young women

back home in Jharkhand. At Khunti, I meet with Serofina Sarong,

a domestic help in Delhi who is back home for a break. Sarong is

a confident young woman and her dimunitive 5 ft frame exudes an

air of confidence. In her room, on an immaculately arranged table

are among some trinkets and cosmetics, a fairness cream and a sun

block. The envious glances other young women, the unlucky ones that

are yet to make it to Delhi, shoot at Sarong are evidence enough

of her standing in this society. Or Hana Tirkey's. All of 19, Tirkey

couldn't clear her high-school examination and, appalled by her

family's poverty, followed a neighbour to Delhi. She spent three

years there as a maid, saved around Rs 50,000, repaid the family's

debts, bought and sold 10 pigs turning a neat profit in the process,

and put away some money in the bank for a rainy day. Now, she proposes

to start a tailoring school.

Tales such as these are common in Jharkhand.

There's Margaret (just Margaret), a 40-year-old who came to Delhi

over 20 years ago and graduated from lowly maid to highly-paid governess.

She put a brother through school and saw him join the Army, bought

four acres of land in Gumla, a district adjacent to Simdega, and

has now retired to Ranchi where she works as a governess. Neighbours

claim she has an investment of Rs 40,000 with Sahara India, a non-banking

finance company, although the lady herself wouldn't comment on her

net worth. And there's Ursula, who made it as far as Dubai and earned

Rs 11,000 a month. She spent three years there, oversaw the marriages

of her three brothers, bought one a bicycle, helped another open

a grocery store in the village, and set up the third as a pig farmer.

She has since returned to India and married a local agriculturist,

but finds living with an ''uncivilised'' husband difficult.

|

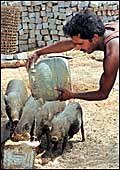

| Pigs are something most women who work in

Delhi buy for their dependants back home. Pig-farming is a low-risk,

high-return vocation |

Home Economics & More

Getting to Delhi, or Dubai, for that matter,

is easy. Placement agencies in the capital (estimates put their

number at 200) recruit local agents across Jharkhand's villages;

these agents scour their constituencies for women who wish to work

in Delhi (or those who can be persuaded to); the agent also carries

out a background and reference check, gets the women to sign a contract

with the placement firm, and puts them on a train to Delhi. Apart

from agents working exclusively for them, most agencies also resort

to freelance 'guarantors' who serve as an informal employment exchange

(apart from vouching for the women on their roster). Placement agencies

pay guarantors half a month's salary of the women referred by them.

The agencies themselves charge employers two

months' salary when they enter into an annual contract: this is

binding on the agency, not the employees; ergo, if a woman deserts

her post, it is the agency's responsibility to find a substitute.

Most agencies double up as halfway houses of sorts for women between

jobs and those that have just arrived from Jharkhand.

The prevalence of public call offices (PCOs)

in Jharkhand's interior is testimony to the efforts of the state's

émigrés in Delhi to keep in touch with those back

home. And B.M. Kar, overseer of the post office at Khunti says most

post offices in the state exist solely for the purpose of servicing

the remittances sent back home by these women. This, when the majority

of Jharkhand's women in Delhi prefer to carry the cash in person

when they return home for Christmas! Predictably, they receive a

heroine's welcome with some families organising village-wide feasts

for their ''selfless daughters''. Not that the men back home recognise

their efforts. Any woman who spends some time in Delhi is heckled

for being a Dilli Retire, a pejorative with associations that range

from sexual deviance to undesirable modernity. In a society where

marriage proposals have to be made by the groom's family, this results

in several women remaining unmarried. Few tears are shed over these.

Jharkhand's drones are no prize catch.

The life of a typical woman from Jharkhand

in Delhi is far from a Cinderella story. Some are duped by agents,

others framed for petty theft and discharged, and still others,

assaulted sexually by employers. Entities such as Manch and Domestic

Workers Forum, the first a non governmental organisation, and the

second, a forum associated with the church educate the women about

their human and legal rights. However, most women nurse ambitions

of saving enough money to return home and earn their livelihood

there. They may have picked up a smattering of English from the

mission school, dress fashionably, and greet people by extending

their hands spontaneously, but deep down, these tribal women yearn

for the simple and uncomplicated life back home. As long as money

isn't an issue.

|