|

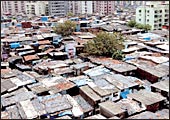

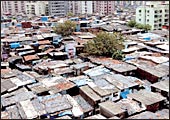

| City of contrast: Spread over 1.75 sq.

km, Mumbai's Dharavi is Asia's largest slum, where thousands

of people live |

Scene 1: Bangalore, Silk Board Junction, morning rush hour.

Cars and motorbikes snake endlessly along the narrow road that

leads to the heart of India's Silicon Valley, the Electronic City.

From the junction, it is less than 10 kilometres to the campuses

of India's best-known it companies, Infosys and Wipro, but the

motorists this morning-most of them employed in the booming it

industry-will take anywhere between one and two hours to reach

their workplace. The irony: The junction did get a new flyover

recently, but nobody bothered to widen the road down the stretch.

It is worse on the way back home, because there's no flyover on

this side. Elsewhere in the city, getting stuck on the Airport

road could mean a missed flight.

Scene 2: Mumbai, early July: It has been raining for four

days and life in the city has come to a halt. Places such as Andheri,

Khar, Malad and Bandra-Kurla Complex are waterlogged, suburban

trains are stranded at several places, and there are reports of

rain-related deaths. It's not the first time rains have brought

Mumbai to a standstill. They did too last year and claimed more

than a thousand lives. Weary Mumbaikars are outraged.

Scene 3: Delhi, Seelampur slums: Crumbling brick-and-mud

houses line the sides of a narrow lane, with open drains running

alongside. There are small heaps of garbage all along, smell of

which mixes with that of excreta in the open drains to produce

an overwhelming odour. But unmindful of the surroundings, children

chase each other around and men sit around on charpoys, smoking

beedis and hookahs. Living in these slums means cooking, eating,

sleeping and washing in barely 10x6 rooms. But guess what? That's

how half of Delhi lives.

| THE TOP 10 CITIES |

| 1 |

MUMBAI |

| 2 |

BANGALORE |

| 3 |

DELHI |

| 4 |

CHENNAI |

| 5 |

HYDERABAD |

| 6 |

KOLKATA |

| 7 |

PUNE |

| 8 |

AHMEDABAD |

| 9 |

MYSORE |

| 10 |

VIZAG |

This is not how

best cities are supposed to be. Best cities aren't supposed to

erupt in violence if an ageing movie star dies at the grand age

of 77, like Bangalore did when Rajkumar died on April 12. Neither

are best cities supposed to let walk-in bombers massacre home-bound

rail commuters like Mumbai allowed on July 11, when more than

200 people died. Best cities are supposed to be places where all

their inhabitants can find material and spiritual fulfilment.

The fact that none of India's cities is so, drives home a grim

fact about our fifth Best Cities for Business survey: These are

best of the worst cities. Power cuts, water scarcity, congested

roads, pollution, dirt and roadside squalor are par for the course

at almost all Indian cities.

Yet, it is these overcrowded and crumbling

cities that drive India and make it the second-fastest growing

economy in the world. Cities and towns are where 30 per cent of

our people live, with 38 per cent of the urban population confined

to just the top 35 cities. Fifty-five per cent of the country's

GDP emanates from urban India; 50 per cent of the foreign direct

investment goes to the seven largest cities. Globally, cities

are the engines of their economies. They are too in India.

But the stress on our cities has begun to

tell. As India's population and economy grew, more and more people

migrated to the cities in search of a livelihood. But the cities

themselves never planned to keep pace with their growth. There

was no urban planning to talk of, resulting in haphazard development.

Poor zoning compliance turned residential localities into commercial

centres, and slums came up wherever they could. Today, 22 per

cent of the city dwellers live in slums, and half of them work

in the informal economy as hawkers, mechanics or roadside vendors.

"A city is not just a place of employment, but a place of

hope," notes Kavas Kapadia, Professor & Head of Urban

Planning at Delhi's School of Planning and Architecture (SPA).

|

| Hi-tech Hyderabad:

One of the more progressive cities, it ranks high in

availability of office space and housing facilities |

Why have we neglected our cities, then? Because

our early political leaders always thought of India as an agrarian

country. Therefore, urban development, a state subject, was never

accorded priority and all the five-year plans allocated token

sums to cities for development. The Mega City Scheme of 1993-94,

for instance, allocated Rs 75 crore to five mega cities for a

five-year period, meaning Rs 15 crore a year. "You can't

build half a flyover with that sort of money," quips Vijay

Dhar, hudco Chair Professor at the National Institute of Urban

Affairs. Property tax is supposed to be the single-biggest source

of revenue for city municipalities, fetching three-fourths of

all revenue collections in cities that don't have octroi. But

thanks to poor compliance, outdated property valuation systems

and leakages, India's cities and towns (more than 5,000 of them)

collect just Rs 12,000 crore a year. Obviously, bigger cities

such as Delhi and Mumbai account for the lion's share of this

money. "If you don't remove regulatory constraints and rebalance

the power equation between the Central government and the states

on the one hand and between the states and their cities on the

other, infrastructure in cities can't be developed," says

Om Prakash Mathur, Professor, National Institute of Public Finance

and Policy (NIPFP).

A large part (70 per cent) of India still

lives in villages, but not quite the way it used to. Agriculture's

contribution to the GDP is shrinking. Between 1990 and 1995, it

accounted for a third of GDP. Today, its share is a little more

than a fifth. More importantly, it has finally sunk into our policy

makers that neglecting our cities is a lose-lose game. When choked

drains bring Mumbai to a halt, there's real business and productivity

loss in India's financial capital. When Bangalore riots and tech

workers aren't able to reach their workplace, companies lose real

export dollars. In other words, when our cities lose, India loses.

"Compared to some other cities in the world, we are 180 years

behind in city management and, therefore, have to fight 180 times

harder to come up," says SPA's Kapadia.

|

| The IT boom: The

outsourcing wave has bettered lives for many, but millions

more have been left untouched |

A Plan To Save Our Cities

Thankfully, an ambitious urban renewal plan

has been put in place. Last year in December, Prime Minister Manmohan

Singh announced the setting up of the Jawaharlal Nehru National

Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). It draws a lot from the Urban

Reform Incentive Fund announced in the 2002-03 budget by the then

Finance Minister, Yashwant Sinha, but it differs in two key aspects:

Compared to the Rs 500 crore that Sinha allocated to the fund,

JNNURM boasts a staggering Rs 50,000 crore against matching contributions

by recipient cities. More importantly, it makes it mandatory for

cities to get their governance and accountability in place before

laying their hands on the fund. "In the scale of its ambition

and the nature of its rigour, JNNURM has no parallel," says

Ramesh Ramanathan, National Technical Advisor to the mission.

He isn't exaggerating. It's for the first

time that India has started on a concerted effort to renew its

urban centres. Unlike in the past, money isn't to be allocated

and spent in dribbles and drabs. To start with, the mission has

identified 63 cities, based on criteria such as the size of population

and tourism potential, for development. An estimated Rs 1,20,536

crore is required to develop these cities, half of which will

come from the Central government. The matching rest must be raised

by the cities themselves. Since JNNURM has sweeping goals, it

is easier to mention what sort of projects don't qualify for assistance.

These relate to power, telecom, health, education, wage employment

and employment creation. Everything else-widening of city roads,

improving water supply and sanitation, and even relocation of

slums-is admissible for assistance.

|

| Urban champ: Union Secy Baijal is driving

JNNURM |

The mission money won't come free. Since governance

and accountability have been the reasons why our cities never

kept pace with growth, there is a string of mandatory and optional

reforms at the level of urban local bodies (ULBs) and states.

For instance, it is mandatory for the beneficiary municipality

to adopt modern, accrual-based, double-entry system of accounting

so that a city's profits and losses are clearly visible to its

citizens. It is also mandatory for it to introduce e-governance,

using software such as GIS (geographic information system) and

MIS (management information system) for various civic services.

The cities must also reform property tax using GIS, so that a

more realistic market rate can be determined depending on the

zone, and bring in appropriate user charges for services such

as water.

The states, on their part, have to hand over

urban management to ULBs as per the 74th Constitutional amendment,

and repeal the Urban Land Ceiling and Regulation Act and the Rent

Control Act to balance the interests of landlords and tenants.

In addition, they must bring down stamp duty to 5 per cent to

encourage registration of property transactions and enact a public

disclosure law to ensure fiscal transparency and discipline among

ULBs and parastatal agencies. To get the funds, the cities must

first come up with a city development plan (CDP), get it appraised

and approved, and then provide a detailed project report for each

project or sets of them. "It's a perfect balance of incentives,

reforms and design," says Ramanathan, who also runs a Bangalore-based

NGO, Janaagraha, focussed on urban reforms.

|

| Highway drive:

New and better roads are getting built, but not fast enough

to keep pace with the increasing demand for connectivity across

India |

Given India's fractured polity, it's a lot

to ask of Indian states. But, happily, the response has been spectacular,

although the mission is just seven months old. Thirty-two cities

have already submitted their CDPs, of which 18 have been approved

and the rest are under appraisal. "To be honest, the response

is way beyond my expectation. There's now a competitive spirit

emerging among our cities," says Anil Baijal, Union Secretary

for Urban Development and the man who, everyone says, has been

championing the mission. He expects all the other CDPs in by end

of August.

A Virtuous Cycle

Not everything is hunky-dory, though. Key

cities including Bangalore and Delhi haven't yet finalised their

CDPs. Bangalore did submit one, but it was sent back for improvement.

Delhi, because of its peculiar position as both the seat of Union

government and a state, has yet to get its act together. For instance,

the municipal commissioners are appointed not by the state, but

the Centre. The biggest threat to the mission lies in the cities

and states not agreeing to the mandatory reforms. For, that is

really what will trigger a virtuous cycle of improved revenue

collections, investment in infrastructure, growth and, hence,

more revenues. The mission only has a longevity of seven years,

meant to coincide with the 11th Five-year Plan, and the cities

in that time must prove that they can be self-sustaining. "This

window is available to take the cities up to a point. Thereafter,

they have to earn their own bread," says Baijal.

|

| City of joy?

Even as new office buildings and residential complexes come

up in Kolkata, the city scores poorly in terms of cleanliness

and healthcare |

Where the money from revenue collections and

grants is not enough, the cities will need to raise money from

markets or multilateral agencies. For that, Baijal, who retires

in two months, plans to get all the 63 cities credit rated by

international agencies. There's also a pooled finance development

fund (of Rs 500 crore) that will allow the weaker of the 63 cities

to use it as a cushion to bolster their books.

Finally, as Baijal points out, the success

of the mission depends on the ownership of the local community.

The people of a city have to become more involved in the running

of their cities. Because, more than good roads and green gardens,

cities are us.

|