|

The

tea didn't help. Nor had he expected it to. Vivek Dani, the Chairman

and Managing Director of India White Limited, one of the country's

largest fast moving consumer goods companies, couldn't still put

his finger on why the four-year-old back-to-basics strategy of getting

more consumers to try his company's products and following that

up with a channel onslaught to increase their availability hadn't

paid off. The

tea didn't help. Nor had he expected it to. Vivek Dani, the Chairman

and Managing Director of India White Limited, one of the country's

largest fast moving consumer goods companies, couldn't still put

his finger on why the four-year-old back-to-basics strategy of getting

more consumers to try his company's products and following that

up with a channel onslaught to increase their availability hadn't

paid off.

Sipping milk-less lemon tea (yes one of his

own brands), on a bright Sunday afternoon at his south-Mumbai penthouse,

Dani mulled over the statistics, once his most potent weapon in

persuading the board to give its go-ahead to Operation Hinterland,

the name his core team had conjured up for a massive sampling exercise

across rural India.

The rationale was straightforward: 70 per cent

of India's population lived in villages, around 6 lakh of them;

and 85 per cent of this rural population lived in villages with

a population less than 2,000. Even with 50 per cent of its sales

coming from rural areas, there was still a huge base of potential

consumers out there that had never used any of India White's products.

Consumers in these smaller-than-small villages

were using either natural substitutes (neem twigs instead of toothpaste

and toothbrushes) or at best, cheap local-made products. Getting

these non-users to try, and then become regular users of the company's

products had seemed like a great idea.

Dani remembered how hard Ashok Khanna, the

company's then marketing director, now on a prestigious assignment

with India White's parent in Europe, had argued to get the project

through.

''If we can address issues of awareness and

availability and back it up with overcoming prevalent attitudes,

primarily through introducing the consumer to our products, via

free sampling, we can capture virtually the entire shift in consumption

from unbranded/natural alternatives.''

Every word had seemed plausible. Dani had just

taken over as chairman and managing director from his illustrious

predecessor, inheriting an enviable 20 per cent plus top-line growth,

quarter-on-quarter. And like any new CEO, he had wanted the company's

future path to bear his own, unique, successful signature.

Khanna's recipe looked perfect, and it helped

that agricultural growth and income was on the upside, for the eighth

year on a row.

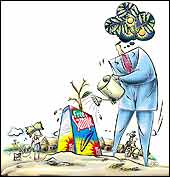

What followed had been a marketing man's dream

come true. India White had literally painted the hinterland red.

Every manager, down to the lowliest management

trainee, had gone out with the sales force, and the company had

managed to round up a huge army of gram sevaks, distributing free

samples of soaps, toothpowder, toothpaste, detergents, and tea.

Not content with just distributing the product, this batallion of

frontline pros had also sold the benefits of the products they were

trying to sell to rural consumers.

Dani remembered how on several occasions he

had himself rolled-up his sleeves and scoured dusty rural roads

in as many as six states, accompanied by India White's head of finance

Venkatesh Raman.

He also remembered how Raman had irritated

him with repeated questions concerning the returns on the tens of

crores the company was investing in the promotion.

A year into Operation Hinterland, the results

on penetration, product usage, and top-of-mind awareness in the

targeted villages, had given Dani enough reasons to cheer.

The company's performance had improved 100

per cent on all counts. The top-line had looked healthier, growing

at over 25 per cent.

Raman had warned Dani that dividends would

have to be pruned as a result of the huge investments in Operation

Hinterland that hadn't really started paying off. ''We'll sell the

story of how we're investing for future profits, and we already

have growth to show.'' Dani remembered how he had silenced Raman

with that one remark.

Khanna, of course, had become a star. At a

bash thrown in late 1999 to celebrate the success of the project

Dani had announced a much-sought-after European assignment, for

him.

Then, in 2000, things had started going wrong.

The year had started normally, but by June, it had been evident

that the urban markets were in recessionary mode.

Dani had quietly congratulated himself for

having invested in rural markets-for these had held out the promise

of growth. By end-year, though, it had become clear that the promise

wouldn't be delivered on.

India White's growth rate had more than halved

to 10 per cent. And a cursory analysis of the numbers had shown

that Project Hinterland hadn't done what it was expected to: urban

demand had remained low, and rural demand, which Khanna had been

so sure would kick-in and grow India White's turnover, hadn't.

The following year, 2001, had been worse. The

rural markets, which had at least held their own in 2000, went on

a downward spiral. Growth had dropped to single-digit levels, and

while Raman had managed to squeeze out consistent improvements in

profits through aggressive cost cutting and process-improvement

techniques, Dani had realised that they would need more than that.

Most importantly, the markets targeted by Operation

Hinterland had simply refused to react to India White's overtures.

In contrast, the company actually managed to

increase its marketshare across categories in shrinking urban markets-a

fact that had prompted Khanna's replacement, Ashish Kumar to come

to Dani recently with a Project Hinterland-like sampling campaign

targeting the urban market.

By the time Dani finished his third cup of

tea and four years worth of rumination, it was late evening, and

he could see the beautiful orange-red aura of the setting sun all

over the Arabian Sea.

He had made up his mind on a course of action:

One, he would speak to Khanna, now somewhere in Belgium, and grill

him on the finer aspects of Operation Hinterland-something he should

have done in those heady days of the late nineties, but hadn't.

Two, he would listen to what Ashish Kumar had

to say on a new sampling exercise in urban markets. And three, he

would never again miss the routine Sunday-evening walk because of

work.

1 2

|