|

On

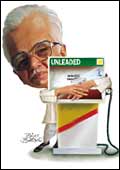

the morning of October 3, a team of five Indian Oil Corporation

(IOC) executives descended on the IOC petrol station attached to

Mumbai's Centaur hotel. Earlier in the year, on June 5, 2002, the

government had sold its stake in the hotel to Batra Hospitality

for Rs 83 crore. And the petrol station had been transferred to

the new owners (as indeed, it should have been). On the given morning,

four months after the event, the IOC execs claimed the ownership

of the station reverted to them the instant the hotel was sold.

A day later, the Disinvestment Ministry, while sharing details of

the transaction at a press conference, produced proof to show that

the Petroleum Ministry had known all along about the transfer, but

the damage had been done. Union Petroleum Minister Ram Naik, the

stormy petrel of the anti-disinvestment brigade had made his point.

If arbitrary acts needed to be undertaken to scuttle the disinvestment

process then he, Naik, would get people from one of the several

oil companies he controlled to undertake them.

Mr Naik, of course, has repeatedly pointed

out (as he did in an interview to this magazine last year) that

he isn't ''against disinvestment in the oil sector per se, but only

against the sale of a strategic stake in the oil PSUs because it

does not come with any real advantage''. Instead, he'd love to divest

up to 49 per cent of the government's stake in them to the public

through an Initial Public Offering. The larger motive: to give the

public a share of the profits of the oil-sector PSUs. That's as

altruistic as motives can get; only, the path suggested by Naik

will also ensure that the oil PSUs remain under the control of the

Petroleum Ministry.

Unlike some

of his ministerial colleagues, though, Naik's opposition to the

disinvestment process isn't a proxy fight on behalf of a corporate

group. The man seems rooted in the socialist mindset of India's

past that considers all big business evil. And nothing-not even

Pumpgate, the scam surrounding the allocation of petrol stations

and LPG agencies, something that prompted Prime Minister Atal Bihari

Vajpayee to cancel all allotments since January 2000-gets him down.

Naik does have several achievements to his

credit. In his tenure, the waiting list for a LPG connection has

come down from 1.1 crore to zero. Exploration activity, too, has

got a boost under him: the ministry has awarded contracts for the

exploration of 47 blocks in the past four years, and received bids

for 23 new blocks; in the 10 years preceding that, contracts were

awarded for exploring just 22 blocks. And by ensuring that India

remains self-sufficient in refining (a capacity of 116.5 million

tones), Naik has saved it precious foreign-exchange that would have

otherwise gone into the import of more expensive petrol and diesel,

rather than the crude it now does.

Unfortunately, it won't be for any of this

that the man who started his career as a clerk in the accountant

general's office in Mumbai, will be remembered. It will be as the

man who stalled the disinvestment process just when it looked like

nothing could go wrong with it.

-Ashish Gupta

REPORTER'S

DIARY

Kabul Inc.

Our

intrepid reporter-photographer duo set out to find the business

side of Kabul...

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A Day In Kabul: (From top) Kabul's main

thoroughfare, the City Road; the Shams Market, one of the city's

business centres; and a typical Kabul shop |

What must be the

quote of our day-long trip to Kabul piggybacking a Confederation

of Indian Industry delegation to the 'Made in India' exhibition

comes from Adi Godrej, the slim, wiry chairman of Godrej Soaps.

"Nothing can sell in Afghanistan right now," says Godrej.

"The internal administration is yet to settle". Then,

after a pause, "... but consider the size of the market, a

mere 27 million". Our efforts to find Kabul Inc, then, proved

futile. Still, the trip had its points. Here's what we learnt.

Geographical co-ordinates: Latitude: 34°,

33"N. Longitude: 69°, 13"E. Elevation: 5,876 feet.

(Actually, we needn't have come here to find this out)

Population: 27 million

Currency: The newly introduced Afghani that

trades at 50,000 to a US dollar, but there are three currencies,

other than that currently in circulation throughout Afghanistan-the

Pakistani rupee, the Iranian Dinar, and the old Afghan currency.

Money-changers are easily found, especially if you have dollars.

Just stand in a crowded thoroughfare and wave a greenback about.

Cars: No one is quite sure how many cars there

are in Kabul, or in Afghanistan. One estimate (from CII) suggests

50,000. Bicycles are the preferred mode of transport. We saw cars

of all makes, from Toyotas to Nissans to Pajeros. Kabul doesn't

have a public transport system in place, but there are private mini-bus

operators.

Phones: We didn't come across any shops vending

prepaid cellular connections of AWCC (Afghan Wireless Communication

Company), the Afghan cellular services company that launched its

service in June 2002. To date, it has sold 18,000 connections at

$370 a pop. Airtime costs Rs 40 a minute on an average. Afghanistan

also has a rudimentary terrestrial network, which they call Digital

Access Phone, and boasts a teledensity of 0.92 per 1,000 pop.

Organised retail: We didn't see any super-markets.

There are the usual Mom & Pop stores and, surprise, surprise,

they do stock a wide variety of products from countries as diverse

as Iran, China, and Pakistan. Kabul itself seems to have more than

its share of medical stores. Our driver told us that most of these

were run by Pakistani nationals and sold spurious drugs. Expectedly,

the average life expectancy of an Afghan is 40.

Entertainment: Asia's medium, the VCD, it is

for Afghanistan. We see several shops with Bollywood titles (pirated,

of course)

What we got back: A kilogramme of Chinese tea

(yup, it's there to be had in Kabul and quite popular too), for

under $2.

What we ate: Kebabs and Afghan bread, for just

about $3. All the water we saw was bottled. The Kabul river was

dry.

Number of investment bankers in Kabul: Zero

Number of bank-branches we saw: 1 (Da Afghanistan

Bank).

Our take: India Inc has no rational reason

for being in Kabul. There's more opportunity at home. Of course,

if we want to act the region's dude and do something for a neighbour,

it is another issue.

text by Moinak Mitra & photographs

by Shome Basu

ILLUSION

The 6.7 Per Cent

Mirage

Actually, industry has grown by a whopping 6.7

per cent in the first five months of this fiscal, but here's why

it won't be able to keep up the pace.

Just

when everyone who was anyone in India Inc was beginning to despair,

comes the strangely sanguine statistical fragment concerning industry.

Industrial growth-a function of the behaviour of six core industries,

steel, cement, electricity generation, coal production, crude oil

and refining throughput-which clocked an anaemic 1 per cent in the

first five months of 2001-02, did a staggering 6.7 per cent between

April and August this year. The cement and steel sectors have been

at the vanguard of the growth returning figures of 11.6 per cent

and 8.9 per cent respectively-last year, they did 1.2 per cent and

1 per cent. Just

when everyone who was anyone in India Inc was beginning to despair,

comes the strangely sanguine statistical fragment concerning industry.

Industrial growth-a function of the behaviour of six core industries,

steel, cement, electricity generation, coal production, crude oil

and refining throughput-which clocked an anaemic 1 per cent in the

first five months of 2001-02, did a staggering 6.7 per cent between

April and August this year. The cement and steel sectors have been

at the vanguard of the growth returning figures of 11.6 per cent

and 8.9 per cent respectively-last year, they did 1.2 per cent and

1 per cent.

So, are we, in all our collective wisdom allowing

our fatalist gene to call the shots when we feel the economy is

headed nowhere? Not quite, say most economists. ''These statistics

do not take into account the impact of the drought,'' contends Pronab

Sen, Advisor, the Planning Commission, referring to the drought-like

conditions (that's how the government likes to refer to it) witnessed

in most parts of northern India this year. The impact of the drought

will likely be evident in the performance of the core sectors in

the coming months. That could dent that industrial growth statistic

some.

Still, most analysts expect industry to do

better this year than it did last when it grew 3.1 per cent. The

Planning Commission's Sen predicts an industrial growth of 5.5-6

per cent; Tabassum Inamdar, an analyst at Kotak Securities, 4 per

cent. But why have the steel and cement sectors outperformed all

other sectors this year? The growth of the steel sector, and the

recent jump in steel prices-from $160 for a tonne of hot rolled

coil in December 2001 to $270 in August-have left most steel pundits

baffled. Some point to an increase in India's steel exports, from

3 million tonnes in 2001-02 to 3.5 million tonnes in 2002-03, mainly

to China and a few south East Asian countries. Others attribute

the growth to The US' efforts to protect its domestic industry by

levying anti-dumping duties on steel imports from Japan, China,

and the European Union; India is outside the purview of these duties,

they explain, and is benefiting from them.

A.S. Firoz, an advisor to the Ministry of Steel

expects prices to come down in the last quarter of 2002, on the

back of global overcapacity in the sector, and while there are no

signs of that happening as yet it is simply a matter of months before

it does: growth in global steel capacity, at 6 per cent, outstrips

that in demand, at 4.6 per cent. And with the world market already

weighed down with some 200 million tonnes of steel it doesn't need,

prices will soon crash.

The Indian cement industry suffers similar

ills. It boasts capacity that is 30 million tonnes in excess of

what it needs. Kiran Nanda, the Chief Economist at cement major

Gujarat Ambuja expects the good times to roll on. ''With the impetus

on housing and roads, the demand for cement will increase substantially

in the future.'' Her estimates: a consumption growth in excess of

12 per cent a year over the next two-three years.

Other analysts are more circumspect. A Mumbai-based

investment banker reckons cartelisation is behind some of the industry's

gains. ''There are no large greenfield projects in the offing,''

he argues. Take that 6.7 per cent with a healthy pinch of salt,

then.

-Aashish Gupta

|