|

In

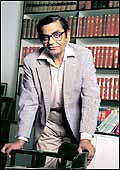

the early 1960s, a young Sydenham-Cambridge-MIT-Oxford educated

professor at the Indian Statistical Institute started narrowing

his eyebrows in suspicion at India's import-substitution policy

framework. Little did he guess that he would emerge-in American

academia-as the lead advocate of Free Trade, influential enough

to herald what the MIT economist Paul Samuelson has called 'The

Age of Bhagwati'. In

the early 1960s, a young Sydenham-Cambridge-MIT-Oxford educated

professor at the Indian Statistical Institute started narrowing

his eyebrows in suspicion at India's import-substitution policy

framework. Little did he guess that he would emerge-in American

academia-as the lead advocate of Free Trade, influential enough

to herald what the MIT economist Paul Samuelson has called 'The

Age of Bhagwati'.

'History has its unforeseen ironies' was the

opening line of Bhagwati's 1993 book India In Transition: Freeing

The Economy. For a nibblet of his conceptual clarity, glance at

the book's contents. Just three chapters: The Model That Couldn't,

What Went Wrong? and What Is To Be Done? Indian liberalisers were

floored.

As the world threatens to recede into protectionist

cocoons, what with America fattening its farmers while blocking

European steel and Chinese brassieres, the WTO advisor and Columbia

professor's thoughts could do with fresh amplification.

Free

Trade works, as Ricardo showed, via the efficiency of every country

pressing forth its comparative advantage to satisfy global needs.

This helps maximise growth, and that's good-even for the poor. While

reciprocal barrier-lowering is desirable, if other countries reject

good trade sense, "then, go thou alone" and grant unilateral

market access, advises Bhagwati, inspired by Tagore. Talk of 'trade

concessions' exasperates the professor-as if granting access is

painful. It is, instead, beneficial. "Except in the few cases

(rarely applicable to poor countries) when strategic tit-for-tat

play is credible, the net effect of matching others' protection

with one's own is to hurt oneself twice over," he says.

What miffs Bhagwati even more is the clamour

for trade with a 'human face'. It has always had one, he argues.

And why call WTO's Doha Round a 'development round'? Development

was always the objective (and trade, the policy).

Yet the professor doesn't approve of 'trade-related'

issues such as intellectual property being forced onto the WTO agenda;

why turn it into a "royalty collection agency"? His best

wit, though, is reserved for economics-savvy audiences. "If,

in lieu of autarky," he once quipped, "the wretched apple

had been traded for something more innocuous, Adam and Eve would

have continued in bliss."

|