|

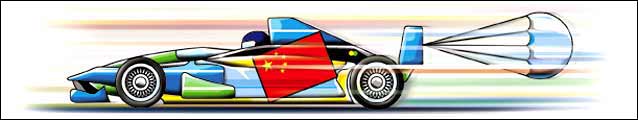

Policymakers

in most parts of the world tie themselves in knots over how to speed

up the economy. In China, they worry about how not to go too fast.

But before you hit the envy button, consider this: Moderation of

the reckless is often more difficult than stimulation of the sluggish.

And always more thankless; the risk of a catastrophe is not something

everybody can plainly see. Policymakers

in most parts of the world tie themselves in knots over how to speed

up the economy. In China, they worry about how not to go too fast.

But before you hit the envy button, consider this: Moderation of

the reckless is often more difficult than stimulation of the sluggish.

And always more thankless; the risk of a catastrophe is not something

everybody can plainly see.

The task that China has set for itself, to

keep its economy within safety limits of growth, is by no means

easy. But it is of huge importance to the rest of the world, which

is why analysts are watching so closely. It helps that the country's

objective has been spelt out clearly: to slow its GDP growth rate

from nearly 10 per cent to a less blistering seven per cent or so.

This is not a precision science, but Chinese analysts reckon that

double-digit growth could result in a sudden flaring-up of the economy,

followed perhaps by a crash if key indicators burst out of their

control gauges. With an economy so fraught with activity, safety

is the need that emphasises itself.

This is not the first time China has attempted

such a thing. It did so in 1992, leaving external observers marvelling

at the country's sense of self-appraisal. The economy's lower limit

then, as now, was judged to be seven per cent. Anything slower than

that, China figured, could spell mass dissatisfaction-to which the

Chinese are not exactly unaccustomed. The upper limit, interestingly,

has not changed much.

But China's role in the global economy certainly

has. Its rapid emergence doesn't cease to startle. Apart from producing

almost every second gizmo and utility product bought in the world,

China already accounts for half of all cement used on the planet,

a third of all steel, and-do take note-nearly a tenth of all crude

oil. If global commodity prices have been so buoyant lately, it

is partly because of China's ravenous appetite for just about everything,

not just Coca-Cola (a brand, which in Chinese says 'thirsty mouth,

happy mouth').

What, then, would the slowdown imply to business?

Prices of assorted tradeables have already declined in response.

So this is broadly what international market analysts expect: lower

Chinese demand for everything, and so, lower prices too.

However, to stop there is to assume that all

will go as planned. This could be assuming too much. Remember, China

tried talking its economy down earlier in 2004, even using what

many consider a blunt tool: direct choking of bank credit. It is

only now, and for the first time in nine years, that it is using

the classic monetary device of raising interest rates overall. The

People's Bank of China has recently hiked its one-year yuan lending

rate-by 27 basis points, from 5.31 to 5.58 per cent. This is how

brake pedals are pressed in functional market economies. Just how

well it works in an economy that is still given to the old habits

of state-driven allocation of funds, is open to question.

Moreover, for all its pragmatism, China's banking

sector remains an opaque engine, and some observers worry that it

is so delicately balanced on a legacy of uneconomic wirings that

any little circuit snap could result in a breakdown.

There's also the issue of China's trade relationship

with the US. For now, China can't get enough of us Treasury bonds

and the us can't get enough of China's exports, but if these cosy

equations get messy, the ensuing instability could rattle the world.

In other words, a plan is only a plan until

it is executed. Still, with the big picture in mind, it is entirely

in the world's interest that China's concerns don't just remain

concerns. It would not have held up its moderation flag without

a keen calculation of the risk in reckless expansion. On that, give

the Chinese credit for some sharp analysis. On what the appropriate

policy responses are, though, more debate would be welcome.

|