|

''Villagers have stopped respecting

us. Earlier they used to receive us reverentially when we went for

revenue inspection. Now they have even stopped offering us coffee.''

Kariappa, 45, Village Accountant

Boriah's

wizened face-aged by years of hard labour under the cruel southern

sun-crinkles as he flashes a toothless grin. He knows of the predicament

of 8,900 men like Kariappa-and he has no sympathy for them.

''They used to be the lords and masters of

the village,'' recalls Boriah, 60. ''Whenever there was a split

in the family, or the land was divided, we had to beg and plead

with the accountant to issue the phani patrike (literally, entitlement

paper). We had to bribe these men to get our land records.''

Sonappa, 28, is from another generation but

his feelings about Karnataka's village accountants, 8,900 of them,

are as virulent. ''Dispute in a family over land meant glad tidings

for the accountants,'' says the farmer with disgust. ''The accountants

made changes based on whoever paid them the most.''

Fifty-seven km south-west of Bangalore in the

village of Hanumanthapura, as in each of Karnataka's 10,000 villages,

there is a great sense of freedom and relief taking hold. There

is a boldness with which villagers rail at the accountants, a group

of low-level bureaucrats who once held absolute power over the village

because of their power over the village's most precious asset and

commodity: land.

|

"Though Karnataka was hailed for its

IT achievements, it was a shame that technology could not be

used to help the masses"

Rajeev Chawla, Bhoomi's chief

architect |

That power over land records has for the first

time been wrested from the accountants in Karnataka thanks to a

complex but easy-to-use computer system that has gone online in

each of the state's 177 taluks.

Today, a villager anywhere in Karnataka need

no longer spend days, weeks, even months, pleading, urging-and frequently

bribing-the village accountant to issue or change a hitherto hand-written

land record. The farmer only has to walk into a village accountant's

office and pay Rs 15 to get a modification done or a copy made at

any time. And thanks to the innovative use of a raft of technologies

(See What's New And Unique), the ability of accountants to manipulate

the system has been dramatically curtailed, if not eliminated.

Our Problems, Our Technology

In easing the life of millions of hard-working

farmers, Bhoomi (land)-as the system of online land records is called-has

shown how widely available technical expertise could be used to

bridge the ''digital divide'' that plagues all of India.

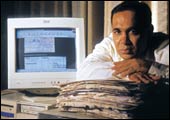

''Though Karnataka, and more specifically Bangalore,

was hailed for its achievements in infotech, it was a crying shame

that technology could not be effectively used to help the masses,''

explains Rajeev Chawla, a portly engineer from IIT Kanpur who is

Karnataka's Additional Revenue Secretary and Bhoomi's chief architect.

As he points out, the giant project-the most ambitious land records

digitisation project ever attempted in India (See Prime Numbers)-needed

no new technology. Just getting Bangalore's plentiful software brains

to evolve clever solutions using existing technology was enough.

It wasn't easy, of course.

|

WHAT'S NEW AND UNIQUE

|

|

BIG, BIGGER, BIGGEST:

The Karnataka Land-Records-Online project is the biggest

such effort undertaken by any state government in India. Land

records are plagued by corruption, manipulation, and great

inefficiency.

TOUCH-SCREEN KIOSKS: Instead

of pursuing the village accountant for a land record, a farmer

must only pay Rs 15, declare name and village on a touch-screen

kiosk, which will print out a copy of his land record.

BIOMETRIC

IDENTIFICATION: To

prevent unauthorised access and ensure that village accountants

take responsibility for changes made in land records, access

to computers is only through a fingerprint scan.

CONTROLLING NET ACCESS: Since

each of the PCs in 177 taluks has internet access, the government

has prevented their misuse by ensuring that the land-record

software pops up as soon as machines power up.

BACK-UP:

Many computer projects have failed because of power failures

and crashes. Apart from ups, each pc has two hard disks mirroring

each other. Back-ups on floppy are also sent to district heaquarters

on a weekly basis.

COMMERCIAL

OPPORTUNITIES: Online land records are a database from

a marketer's dreams. If the government allows it, a car maker,

for instance, can easily find out how many people own, say,

more than 20 acres.

|

It's taken Chawla, his department, and many

infotech companies four years from conceptualisation to final implementation

in March 2002. It involved the sifting, compiling, scanning, and

reviewing-a continuous process, since mistakes from illegible and

faulty records are widespread-of 20 million rural land records belonging

to 6.7 million Karnataka farmers with retrospective effect. Manual

records are now illegal in Karnataka. (If you're interested, the

front-end of the system is Visual Basic 7.0, the back-end MS SQL

7.0, with a Windows NT operating system running software in Kannada).

A land record is actually a voluminous form

with 28 columns maintained as a loose-leaf register (it still is

in most of India). Officially called the Record of Rights, Tenancy

and Crop Inspection, the land record is critical to both the government

and the farmer. It contains all manner of data related to the land:

area, nature and possession of land, whether acquired by registered

or unregistered document of succession, partition, mortgage, tenancy,

assessment, water rate, classification of soil, number of trees,

details of crops grown, land utilisation-there's more. Get the picture?

The Miracle Of Good Governance

In rural India, land records are vital documents,

needed to secure crop loans, establish ownership, lineage, and formulate

government schemes. The manual system of land records is one of

the key reasons for widespread corruption in rural India. The village

accountants do not open records to public scrutiny and updating

them has been a process plagued by delays, corruptions, and flaws.

Even if the accountant is honest, delays were endemic because each

accountant handles four-to-five villages. The system was decentralised,

which means this vast data meant little to district headquarters.

Not surprisingly, there are nearly 80,000 cases

relating to rural land disputes pending in Karnataka's courts, according

to government estimates. The system was so flawed that even government

land could be usurped, says Chawla. In Bangalore division alone,

the records of Rs 250 crore worth of government land has been shown

in the name of influential people who manipulated the system.

|

PRIME NUMBERS

|

| Number of farmers |

6.7 million |

| Land records

online |

20 million |

| Village accountants |

8,900 |

| Accountants

retrained |

531 |

| Cost of project |

Rs 20 crore |

| Monthly payback

(from user charges) |

Rs 72 lakh |

| Cost of land-record

copy |

Rs 15 |

Apart from making the accountant accountable

for all changes, Bhoomi alerts higher officials if cases are pending

for a month-after which the accountant must explain the delay. At

a key stroke, supervising officials can now monitor work instantly.

The only other project anywhere near this scale

is Andhra Pradesh's computerisation of land registration, but it

pales in comparison because it only registers land sales and has

no record of transactions previous to digitisation.

The Government of India has already recommended

Bhoomi as the system of choice to states moving to digitise land

records. Goa is implementing a similar system, and the governments

of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Sikkim, and Delhi have contacted

Chawla for assistance. Bhoomi has been shortlisted for the prestigious

international Stockholm Challenge Award for public service technology

projects.

A great incentive to take Bhoomi countrywide

is that it will eventually be self-sustaining. The Rs 20-crore project,

financed by both the state and Central government, has already earned

the government Rs 4.7 crore in user charges. It is quite evident

that rural users are only too willing to pay nominal fees if service

is guaranteed. There are even accountants who welcome Bhoomi. ''It's

easier for honest accountants,'' says Nagaraju, 47, of Hoothagere

village. ''No more cumbersome writing.''

For those, who bemoan the passing of the free

coffee and forced respect, it's time to move on.

|

TREADMILL

|

Getting

Camara's Quads Getting

Camara's Quads

It's been a week since the

world Cup reached its climactic finale, but I still can't

get over the images on the TV screen. And I'm not talking

about the goal shots, the exquisite tackling moves or the

great saves. I'm talking quadriceps, hamstring and calves.

Or, simply, legs.

I don't remember which match it was-probably the one between

Senegal and Sweden, where Henri Camara got the golden goal-but

a friend and I decided to watch it over a case of beer. It

was a lazy Sunday afternoon and both of us were in shorts.

Big mistake. Because, whether you like it or not, you're going

to compare your spindly legs to the awesome quads, calves

and glutes on display for a full 90 minutes. And feel miserable.

My friend made it worse by reeling off some trivia: on an

average a professional footballer runs nearly 11 kilometres

during every match he plays. And of how footballers are among

the fittest sportspeople. The beer tasted flat as both of

us tried to hide our legs under our chairs.

Legs are the parts of the body that are most neglected by

men in gyms. There's a reason for that. Leg exercises are

boring. Squats, leg presses and hamstring curls don't have

the macho feel of bench presses or preacher curls. And, of

course, we normally wear trousers, so the incentive to get

great legs is less than, say, ripped arms.

But then, legs support the rest of your muscle-bound body.

That's reason enough to focus on them even if you're not the

beach-combing type. It could be good idea to do exercises

focused on your legs at least once a week. While machine-oriented

exercises like leg presses, leg extensions or hamstring curls

are good, it's the freehand and free-weight exercises that

hit the spot. And for legs, there's nothing better than a

few sets of squats. I've talked about squats earlier in Treadmill

and mentioned how they're not easy exercises. If squats are

not done properly, you risk knee and lower back injuries.

But it's not difficult to learn how to squat in good form.

First, try squatting without weights. Keep your head high,

shoulders back and hips low. Your feet should be about shoulder

width apart and rooted to the ground. And when you squat,

your back shouldn't bend and your thighs should be parallel

to the floor. When you've mastered the move, start holding

a barbell without weights behind your back and across your

shoulders. Then, after a few weeks of that, add weights. In

a few months, go out and buy a pair of snazzy shorts.

-MUSCLES MANI

|

|