|

State

Bank of India (SBI) may be nowhere near the top of the heap of

this magazine's Best Banks survey-it's somewhere down there at

#29, albeit an improvement over the previous year's #36-but as

far as size goes, SBI is easily numero uno by far (unfortunately

there's no BT-KPMG award for the largest bank this year). After

all, with a deposit base of Rs 3,67,048 crore as of March 2005,

SBI-minus its associates and subsidiaries-is head and shoulders

above the rest of the Indian banking pack, Punjab National Bank

coming in a distant second, with a deposit base of a little over

Rs 1 lakh crore.

Now consider SBI on the global stage, and

suddenly it doesn't appear that large anymore. If you go by the

2005 study of The Banker, the Indian behemoth just about makes

it to the list of top 100 banks of the world, with a #93 ranking.

The good news for A.K. Purwar, Chairman, SBI, of course, is that

his is the only Indian bank to feature in The Banker's top 100.

If Indian banking is today at the crossroads, it's not because

there aren't enough of them going around (there were close to

300 of them at last count, including foreign, PSU and regional

banks). The problem is there aren't enough of global scale and

size going around. And that's one reason why India remains an

over-banked, under-serviced market. As Malcolm Knight, General

Manager of the Basel, Switzerland-based Bank for International

Settlements (BIS), an international organisation that fosters

international monetary and financial cooperation, puts it: "India's

banks must realise they have to be able to compete with foreign

banks (globally)." That clearly calls for a frenetic bout

of mergers & acquisitions (M&As), with public sector banks

either merging or acquiring their state-owned counterparts, and

foreign banking groups being allowed to acquire local banks. But

as Usha Thorat, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, pointed

out recently at a FICCI seminar: "Banks still have to work

on this."

|

"We

are focussing our strategy towards well-rounded organic growth

in both our corporate and consumer businesses by leveraging

our deep local understanding and global presence"

Sanjay Nayar

CEO (India) and Area Head, Citibank |

Thorat's dead right. According to a Morgan

Stanley study, in 1997 India had 58 banks, excluding foreign bank

subsidiaries and regional rural banks. Now compare that figure

with Malaysia, which had all of 54 banks eight years ago. The

figure at the end of 2004: Just 10. That's one reason why the

top five banks in Malaysia control three fourths of the assets

in that market, up from 58 per cent in 1997. In India, however,

the asset share figure barely inched upwards from 41 per cent

to 43 per cent between 1997 and 2004.

If you're wondering about the merits of such

rationalisation, well there are many compelling ones: One, there

are just too many banks competing for the same share of the pie,

which may be growing rapidly today, but that growth rate will

some day in the not too distant future whittle down as the base

factor comes into play. Two, if Indian banks want to arrive on

the global map and compete on a global level, they need to develop

size fast, as barring the top few, none features even in the global

300. Inorganic growth via mergers is one way to develop that size.

From the capital point of view, a merged entity will be better

placed to meet the Basel II norms, to invest in technology and

to penetrate deeper on a regional basis. Customers, in turn, will

benefit via lower transaction costs, as the merged banks gain

from economies of scale. The bottom line: With banks becoming

more efficient on the distribution, technology and capital fronts,

they will be a lot safer.

Consolidation will also help Indian banks

spruce up on the profitability front. Although return on assets-

a key measure of a bank's profitability-has improved from 0.6

per cent to a little over 1 per cent between 2000 and 2004, it's

still below the global benchmark of 1.5 per cent. Return on equity

too is a couple of notches below the global norm (18 per cent

as against 20 per cent-plus).

|

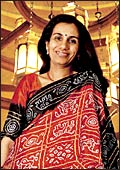

"Organically

we have been growing fast at more than 35 per cent on a year-on-year

basis, yet we will not hesitate to seize the first opportunity

that's large enough for us to grow faster than that"

Chanda Kochhar

Executive Director, ICICI Bank |

Indian public sector banks, for their part,

appear to have recognised the benefits of consolidation. Quips

K. Cherian Varghese, Chairman & Managing Director, Union Bank

of India (UBI): "UBI was seen as a bridegroom; I would not

like to remain a perpetual bridegroom, and I hope something happens."

Varghese agrees that consolidation is an attractive proposition

and a lot of opportunities do exist. In fact, a merger proposal

with Bank of India was blueprinted, but nothing's come of it yet

thanks to opposition from the most likely quarters. "We are

opposing the merger as we do not see the need for it," says

P.K. Sarkar, General Secretary, All India Union Bank Officers'

Federation.

Yet, with consolidation having the blessings

of the Finance Minister and the central bank, the feeling amongst

industry circles is that the inevitable can only get delayed,

not shelved. Already whispers of mergers proposed along regional

lines can be heard in bank corridors. For instance, there's talk

of UCO Bank and UBI Bank, both of which have their headquarters

in Kolkata, along with possibly Allahabad Bank, being merged into

a single entity. Similarly Indian Overseas Bank and Indian Bank

in the South could be amalgamated. But what looks the most probable

is the merger of SBI's seven associate banks into the parent.

The private banks, for their part, are on

the lookout for potential targets. HDFC Bank CEO Aditya Puri agrees

there are too many banks chasing the same set of customers, which

is resulting in piecemeal bits of the pie for each player. Chanda

Kochhar, Executive Director, ICICI Bank, doesn't have any targets

on her plate, but that doesn't mean she will let opportunity pass

her buy. "Organically we are growing very fast, at more than

35 per cent on a year-on-year basis, but we will still seize the

first opportunity that is large enough for us to grow faster than

that," is how Kochhar puts it.

|

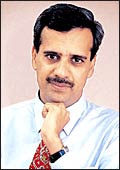

"We are

looking at opportunities within the foreign bank fold in the

short term"

Neeraj Swaroop

CEO (India), Standard Chartered |

The foreign banks, meantime, too want a part

of the action, but they have to bid their time, although last

fortnight reports surfaced about Citibank having sent a proposal

to RBI, showing interest in the troubled Ganesh Bank. Also Australia

and New Zealand (ANZ) Banking Group is reported to be contemplating

a re-entry into India (after selling its operations to Standard

Chartered six years ago), by possibly buying into IndusInd bank.

Both Citi and IndusInd declined to comment on the opportunity

for M&As. That may well be because RBI has chalked out a roadmap

to 2009, which will allow foreign banks to acquire stakes in domestic

ones in a phased manner (currently foreign banks can go up to

49 per cent in private ones, and only up to 20 per cent in PSUs).

The FM, however, appears more enthusiastic about consolidation

than a cautious RBI (which wants to give Indian private banks

more time to shape up), and it remains to be seen whether the

2009 date is advanced at a time when foreign direct investment

is becoming a burning priority.

Perhaps worn out by the rather long wait,

foreign bank honchos sound lukewarm about the prospect of acquisitions.

"RBI has a clear roadmap for the Indian banking sector and

we are accordingly focussing our strategy towards well-rounded

organic growth in both our corporate and consumer businesses by

leveraging our deep local understanding and global presence,"

says Sanjay Nayar, CEO (India) and Area Head, Citibank. Standard

Chartered has been relatively more in the thick of the action,

having acquired two branches of Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp.

towards end-2004, and prior to that Bank of America's retail banking

portfolio as well as Grindlays in India. "In the short term,

we are looking at more such opportunities," points out Neeraj

Swaroop, CEO (India), Standard Chartered.

|

"UBI was

seen as a bridegroom. I would not like to remain a perpetual

bridegroom, and I hope something happens"

K. Cherian Varghese

Chairman & Managing Director, Union Bank of India (UBI) |

The Indian banking sector would do well to

take a look at the pace of consolidation in the rest of Asia.

South Korea began its second round of consolidation in 2001, and

that's helped its banks to improve their credit rating by creating

economies of scale and scope, even as they reduced financing costs,

and did away with duplication of investments in it. In Japan,

the once very crowded domestic banking sector has undergone significant

consolidation, which has resulted in the emergence of five key

banking groups. These banks now hold approximately 46 per cent

of total bank deposits in Japan. Similarly, the Malaysian banking

industry has brought down the number of banks from 55 to 10 and

is poised to enter its second phase of consolidation. This will

involve mergers between banks and their finance company subsidiaries.

If there's one stumbling block to India following

down the same path, it's the unions. Although FM P. Chidambaram

has assured that no retrenchment will take place and there will

be effective redeployment, people like Sarkar of the All India

Union Bank Officers' Federation aren't convinced. "Successful

redeployment is not possible," scoffs Sarkar. His other fears

include clashes of culture, narrowing down of career prospects

and stagnation on the promotion scale. The challenge, though,

is for the managements and promoters (who are the government in

many cases) to recognise the benefits of consolidation, and convince

their employees about those advantages. If they fail to do that,

the realities of the marketplace might show the way. As G. Sankarnarayanan,

Senior Vice President, Indian Banks Association (IBA), points

out: "Even if two stakeholders don't agree, the market will

force them." Hopefully, it shouldn't come to that.

|