|

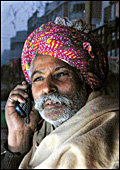

| On the move: No other device quite captures

the zeitgeist of the 2000s |

1

GROWTH

The 65-million Certainty

If things go well

in 2005, one out of every 13 Indians will own a mobile phone. And

if things go badly, one out of every 15 will. India's telcos will

be happy with the first scenario, which translates into 75 million

phones by the end of 2005, but they will not be unhappy with the

second either (which translates into 65 million phones). No one

is arguing about whether India's mobile telephony market will grow;

the two points of view have to do with whether it will grow at the

rate of 35 per cent or at the rate of 56 per cent.

As suggested by either rate of growth, telecommunication

services will be available almost anywhere in India. "Subscriber

growth will be driven by the fact that services will be available

in some 5,000 towns and cities by the end of next year," says

Kunal Ahooja, VP (Telecom), Samsung India. "More coverage is

our priority," adds Amit Khanna, the spokesperson for Reliance

Infocomm. "By the end of next year, we should cover almost

95 per cent of India's land mass." And everyone is convinced

that India will have 100 million mobile telephony subscribers sometime

in the middle of 2006.

Already (at the end of November 2004), only

27 per cent of the country's 36-million GSM-mobile subscribers (the

remainder is made up largely by Reliance Infocomm, which offers

a CDMA-based mobile service) reside in the four metropolitan cities;

36 per cent live in A-circles (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil

Nadu excluding Chennai, Gujarat, and Maharashtra excluding Mumbai);

31 per cent in B-circles (Kerala, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh,

Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Andaman and Nicobar);

and 5.3 per cent in C-circles (Himachal Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa,

Assam, and the North East). Significantly, between October and November,

the C-circles registered the fastest growth (6 per cent), followed

by the B-circles (4.49 per cent) and the metros (2.64 per cent).

And although the growth of the C-circles looks anaemic in absolute

terms (they account only for 9.47 per cent of the total subscribers

added between October and November), the same cannot be said for

the B-circles (41.66 per cent). This, clearly, will be the source

of future growth. "As penetration increases in rural areas,

subscriber growth (in these areas) will continue," says Prashant

Singhal, a consultant at Ernst & Young. There is a caveat, though.

"These new subscribers will not be high spenders and this will

pose new challenges for operators," adds Singhal. That's another

story.

2

LANGUAGE

V For Vern; V For Value-Added Services

|

| Hello?: No English please, we're Indian |

The mobile telephony

market in the philippines is something anyone who has attended telecom

summits in India in the past year (there have been several of these)

would be familiar with. Operators in that country, it is said, generate

around 30 per cent of their revenues from value-added services (vas),

essentially short message service (SMS). To Indian telcos, that

number sounds nothing short of the magical: this year, vas accounts

for 6 per cent of revenues of the typical Indian telco, and that's

a considerable improvement over the 2 per cent it accounted for

last year. That number, most telcos are convinced, will grow rapidly

in the coming year. Reason? "Language, language, language,"

as Sanjay Behl, Head (Marketing), Nokia India, puts it.

Indeed, as mobile telephony becomes a functionally

ubiquitous service in India-something not too many products can

claim to be; soaps and two-wheelers can; credit cards (there are

10 million of them) and debit cards (20 million) cannot-the vernacular

will replace English as the preferred choice for mobile communication,

through voice or messaging. Balu Nayar, Head (vas), Hutch, speaks

gushingly of the difference the company's interactive voice response

system (IVRS) in local languages has made. "In certain markets,

80 per cent of the people accessing the IVRS do not use English;

they are comfortable in their own language." "Language

has always been a big inhibitor for the growth of data (services

such as SMS)," adds Kobita Desai, Principal Analyst, (Telecom

Services and Mobile & Wireless Communications), Gartner.

Vern isn't the only reason vas will take off

in India in 2005 (although it is the primary one). Entertainment,

telcos are discovering, is a big draw, even in smaller centres.

"The success of our Hello Tunes campaign (where a caller gets

to listen to a popular song instead of the boring ring; Hutch has

its own version of the service) and the number of ringtone downloads

happening here have convinced us that mobile telephony is revolutionising

the way music is bought and sold in this country," says Mohit

Bhatnagar, VP (New Product Development), Airtel. "Entertainment

may be an easy thing to get in big cities where you have malls and

multiplexes," says Hutch's Nayar echoing Bhatnagar's sentiment,

"but there are youth in other cities and they are the ones

driving vas, because for them, downloading a clip of a cricket match,

a wallpaper, or a ringtone isn't something for which the money comes

out of their telecom-spend; it comes out of their entertainment-spend."

No prizes for guessing the predominant language as far as entertainment

is concerned (hint: it's not English).

|

| Nokia's Jorma Olilla: He hides it well,

but the is definitely excited about India |

3

PHONES

Made In India

Early in December,

the world's largest mobile phone company, Nokia, announced that

it would be investing $150 million (Rs 660 crore) over the next

four years in a manufacturing facility in India. By late 2005 or

early 2006, the company's President Pekka Ala-Pietila said, the

plant would roll out its first phone. With some 23 million new mobile

connections added in 2004 (not to mention the replacement market

for phones), it was only a matter of time before companies realised

that it made sense to manufacture locally.

The logic behind this move is straightforward:

it may be cheaper to make phones in China, Taiwan or Malaysia, but

they still have to be shipped to India, where imported handsets

attract a customs duty of 5 per cent. That could explain why the

grey market still accounts for four out of every 10 handsets acquired

by Indian customers. "If companies set up base here, they will

be able to offer low prices and combat the grey market, which is

particularly rampant towards lower-end models," says Gartner's

Desai. "Being based in India will enable us to be close to

the customer and adapt our models better (for the Indian market),"

adds a Nokia executive. "It will drive prices down."

Everyone, telcos, handset vendors, analysts,

is convinced that low prices will drive growth. The CEO of one global

handset manufacturer lets on that his company is working on a "Rs

1,000 phone". That could well take the market into the next

level; it was Reliance Infocomm's serious price-play that set off

the last big boom in the telecommunications market, a boom that

shows no signs of petering out.

It isn't just Nokia; Korean electronics major

LG has already announced a $60-million (Rs 264-crore) manufacturing

facility in Maharashtra, and the buzz in telecom circles is that

almost every handset maker of note is evaluating an investment in

manufacturing in India. It is likely companies will set up manufacturing

facilities in the second most happening mobile telephony market

in the world (after China); it is also likely that some outsource

manufacturing to electronics manufacturing services (EMS) firms

such as Flextronics and Solectron that have a presence in India;

however, it is unlikely that India becomes a handset manufacturing

hub for all of South Asia. While companies may find it economically

viable to make handsets in India for sale in the domestic market,

high transaction costs and inefficiencies in the logistics chain

make exports from India all but impossible.

4

PHONES

More For Less

|

| Hold on: This phone you are holding just

got cheaper |

2004 has seen one

phone politely referred to by people as the mango, another, equally

politely referred to as fish, and could well see, before the end

of the year, a Nokia phone shaped like lipstick. No, we kid you

not, but expect things, as in phone shapes, to get even weirder

in 2005. Weird-shaped phones, however, do not constitute a new trend

(shapes will get even more unconventional in an effort to accommodate

even larger screens); nor does the fact that product lifecycles

in the handsets business are getting shorter by the day (one reason

why a phone that costs Rs 25,499 today can be had for Rs 15,499

three months down the line). What will, is something that can be

called the more-for-less phenomenon.

Percy Batliwala, GM (Personal Communications

Sector), Motorola, sums this trend up best when he says, "Vendors

like us will increasingly start offering more features such as colour

screens, cameras, and general packet radio service (GPRS) at the

same price at which an entry-level phone is available today."

That doesn't mean the market for high-end phones will fizzle out.

As Nokia's experience with the Communicator 9500 shows-all 550 phones

that hit Mumbai were sold in two hours flat; the Communicator retails

for Rs 41,990 -that's a niche that has rapidly grown into a very

healthy slice. The PDA (personal digital assistant)-cum-phone has

come of age and could well rule over the high-end of the market

in 2005. What it does mean, though, is that features such as GPRS,

still and video cameras, and colour screens will no longer be the

differentiators between low-end phones and high-end ones. It isn't

just consumer demand that is encouraging handset manufacturers from

jumping on to the more-for-less bandwagon. Telcos too, love low-end

phones that are fully loaded. "To help operators enhance their

revenue potential, you will see even low-end handsets coming into

the market being Java- and GPRS-enabled to facilitate downloads

of applications," says Nokia's Behl.

Another radical change in 2005, as far as the

handset market is concerned, will be the emergence of the replacement

market. "Indians tend to keep their phones for years,"

says Praveen Valecha, Product Group Head (Mobile Phones), LG Electronics

India. "However, as the number of features progressively increase

with a corresponding decrease in prices, the replacement market

will become significant." Customers, then, could go mobile

with low-end, albeit feature-rich, phones and then graduate to high-end

ones.

|

| Healthy living?: Not really, and the

idiot box will not become as information highway anytime soon |

5

BROADBAND

A Step Closer To Nirvana

It's been said

before, most likely in December 2002 and December 2003, but this

time we mean it: 2005 could well be the year of the broadband revolution.

The telecom regulator, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI),

had articulated its belief, in a paper on broadband published last

year, that India was headed for a broadband boom. That didn't happen,

but now the entity is trying to make the surfeit of cable, optic

fibre and copper that traverses subterranean India available to

companies that wish to pipe broadband services through them. There

are still issues related to last-mile access (the debate on whether

broadband companies must lay fresh cable to homes, or use existing

last-mile connectivity from telcos on payment of a carriage fee

is far from resolved) and pricing-in an interview to this magazine

sometime back, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer was emphatic that the

one thing blocking large-scale computer penetration in India was

the price of broadband internet access-but that could soon change.

"Increasingly, you will see low-priced personal computers being

offered by telecom companies in an attempt to push the use of broadband,"

says Neeraj Chauhan, Director (International), eSys Distribution,

one of the world's largest hardware distributors. "This will

be done in a pay-as-you-use-way." Chauhan is right, and the

process has already started happening. Airtel and Reliance Infocomm

already offer a personal computer (pc), broadband connection and

telephone in a bundled-promotion, and the Tata Group recently announced

that it would soon be vending broadband connections and a low-cost

internet-access device developed and powered by chipmaker AMD. However,

this is right now restricted to those areas where these companies

boast last-mile access. Some broadband operators are trying to go

the cable way and while this may work, as Ramesh Krishnan, Country

Manager, Verisign, points out "Because the cable industry is

fragmented, there can never be large-scale deployment of broadband

over cable."

There are two ways out. One is the way Reliance

Infocomm is getting around the problem, by using wide area networks

(WAN) over Ethernet. "This involves setting up a hub in a locality

or apartment complex and drawing 100 megabyte per second cable Ethernet

connections to every household in that locality," explains

Reliance's Khanna. The other is to use Intel's new WiMax technology

that, while expensive, allows the use of cellular base stations

to envelop huge areas (30-50 sq. km) with wireless broadband connectivity,

sort of like Wi-Fi-on-steroids (Bharti is running a WiMax pilot

project in Bangalore). 2005 could well be the year it all comes

together.

6

MARKETING

Logo, No Logo, Logo, No Logo...

Will 2005 see the

entry of the first Mobile Virtual Network Operator (MVNO for short)

into India? It well could. For the benefit of the uninitiated, an

MVNO is a company that buys bandwidth from a telco and then rebrands

it under its own name and goes out and offers the service to customers.

Virgin Mobile, part of the Virgin Group promoted by over-the-top

millionaire Richard Branson, is the best-known MVNO around. Indeed,

when Branson spoke of his interest in entering the Indian telecom

market on a recent visit to the country, it was probably an MVNO

he was considering.

For many years, this was not possible under

Indian regulations. Policy wonks reasoned that allowing MVNOs would

discourage companies from investing in infrastructure, and infrastructure,

the logic continued, was what the country most needed. Now, though,

there is an infrastructure glut, especially in lucrative urban areas.

"The revised New Telecom Policy, 1999, mentions the resale

of space," says Rajat Kathuria, a consultant with TRAI. "I

believe that the Indian telecom market is mature enough for such

virtual network operators to set up shop." Kathuria believes

that virtual long-distance operators will enter the country before

virtual mobile ones do. Then, there are other points of view on

mobile operators. "India is not yet mature enough to have virtual

network operators," says E&Y's Singhal. His rationale:

there isn't enough excess capacity yet. Still, even he is convinced

that the trend will emerge in 2006.

3

REGULATION

Another Rough Year

|

| In the line of fire: TRAI's Baijal canot

make everyone happy |

Spare a thought

for Pradip Baijal, the head of TRAI. No matter what he does, he

does not seem to be able to make people happy (or get good Press,

for that matter). Take the unbundling thing, for instance. Baijal

is all for unbundling the last mile for broadband service. That

meant that a broadband service provider would be able to use last-mile

lines laid by telcos to pipe broadband connectivity into homes (for

a charge, of course). Now, if he gets his way, the state-owned telecom

monoliths will, no doubt, cry foul and allege that he is playing

favourites. And if he doesn't, broadband service providers can accuse

him of watching out for the interests of the state-owned firms.

Three issues, however, will continue to take

up much of TRAI's time (and column space in newspapers) in 2005.

The first is spectrum, or the lack of it. "Spectrum

issues will crop up everywhere," predicts TRAI's Kathuria.

"In mobile telephony, wireless broadband, anything you can

think of and it will be a core issue because it concerns competition

and consumer interests." The signs of an impending battle are

already here with code-division multiple access (CDMA) and global

system for mobile communications (GSM) operators scrapping for the

1,900-megahertz band. For the record, this band was meant to be

reserved for GSM players who could, the reasoning went, use it to

offer third generation (3g) wireless services (actually, most GSM-based

3g networks in the world use this band). GSM players allege that

CDMA companies (read: Reliance Infocomm and Tata Teleservices) are

lobbying to usurp this band and thereby, prevent the launch of 3g

GSM services in India. The CDMA operators claim that they need the

1,900-Mhz band to expand and that their service on this band can

co-exist with 3G GSM services.

Then, there's the common enemy: the Defence

Ministry, whose various arms hog much of the spectrum available.

The second is number portability, which will,

in effect, allow a customer to move from one mobile operator to

another, even from a landline operator to a mobile one without changing

his or her number. In effect, ownership of the number is the customer's.

There's no denying the fact that doing this will make it easy for

customers to shift from one telco to another; in the us, when number

portability was allowed, tens of thousands of customers switched

service providers. Again, there are telcos in favour of this and

those against, and just to make things more difficult, the skill-set

required to effect this isn't commonly found in India.

The third is the debate into the access deficit

charge (ADC) regime that will continue well into 2005. All things

remaining equal, it seems unfair that a telco pay a competitor for

originating and terminating a call on its own network (shorn of

all jargon, that's what happens now). In 2005, Baijal has the unenviable

task of resolving these three issues. And that's only the beginning.

|