|

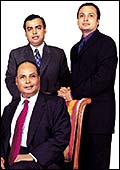

| The Ambanis: Dhirubhai (seated) with

Mukesh (left) and Anil |

Every

weekday afternoon, Mukesh and Anil Ambani drop everything and walk

across from their fourth floor offices to a big rectangular room

that serves as Chairman Dhirubhai Ambani's sanctum during the three

hours that the Ambani patriarch spends each day at Maker Chambers

iv, Reliance's headquarters in Mumbai's Nariman Point. The two sons

have lunch with ''Papa''-a practice that has become a ritual. This

is when the two brothers get to listen to India's foremost entrepreneur,

a man who has achieved in his lifetime what few are bold enough

to dream. It was at one of these lunches, nearly four months back,

that the 69-year-old senior Ambani first talked to his sons about

his latest dream, one that he has just seen come true. It was a

proposal to merge Reliance Petroleum Ltd (RPL), the biggest grassroots

oil refinery company that the Ambanis have built, with parent Reliance

Industries Ltd (RIL). The merger would catapult RIL, already the

largest company in India's private sector, into the Fortune 500

list, a dream that Dhirubhai had cherished for years.

In minutes, the atmosphere of the usually low-key

lunch meeting was electrified. Within days, a core team was formed:

the two brothers, of course, plus Anand Jain, Reliance Capital's

Managing Director; Amitabh Jhunjhunwala, CEO, Reliance Capital;

Alok Agarwal, Treasurer, RIL; and Satish Seth, Director, Reliance

Power, RIHL, Reliance Telecom, and BSEs Telecom. Swiftly the numbers

were crunched, the details thrashed out and the final proposal drafted

in a secret operation code-named Project Aden, an allusion to the

African port where Dhirubhai, then in his teens, cut his teeth as

a petrol station attendant. It was only in mid-February, four weeks

before the official announcement that the financial institutions,

which hold 13 per cent in RIL, and JM Morgan Stanley, the financial

advisors in the deal, were informed about what was to happen.

PETROCHEMICALS:

The merger helps to insulate the petrochem business against

price volatility of naphtha, a feedstock for its cracker.

OIL: In the post-APM scenario,

the merger will help leverage a larger balance sheet to raise

funds that can be invested in setting up a distribution and

marketing network.

DISINVESTMENT: Reliance

is a strong contender in the race to acquire HPCL, BPCL, and

IPCL. The merger will help it make more aggressive bids against

global oil giants.

INFOCOM: Fund-raising for

the Rs 25,000-crore plan to build a nationwide network could

be easier. |

What happened will surely become a landmark

in corporate India's history: the birth of a behemoth. The merged

company will have a turnover of Rs 58,000 crore. That's 23 Infosyses

if you like your units in new economy companies. Or two A.V. Birla

groups, if you're still a dyed-in-the-wool old economy aficionado.

The merged company's annualised net profits will be Rs 4,000 crore.

Or nearly 30 per cent of the total profits of all private sector

companies in India. And if that's not stunning enough, deal with

this: the RIL-RPL combine's total sales will be a tidy 3 per cent

of India's GDP; the tax it will pay the government will represent

10 per cent of total indirect tax revenues of the Central government;

its exports will form 5 per cent of India's total exports and its

stock will command a 15 per cent weightage in the BSE Sensex.

But the fundamental reasons for the merger

are not about size alone. The RIL-RPL merger has not come as a surprise:

it was logical. In the global energy business, standalone refineries

don't make business sense. Refining margins are wafer thin and any

business model that relies on oil refining alone cannot be profitable

in the long run. Average profit margins on refining have fallen

from $4.69 per barrel in third quarter of 2000-01 to around $1.45

per barrel in the third quarter of 2001-02. Only when the entire

chain of the oil business is integrated-from exploration to refining

to marketing and distribution-does it make economic sense. So a

merger with RIL, which consumes a quarter of RPL's output, helps.

Says Miten Lathia, Analyst, SSKI: ''With the merger, RIL has become

a totally integrated energy company. The diverse streams of earnings

would reduce earnings volatility.''

|

THE BIGGER ONE

|

|

RIL

|

RPL

|

POST-MERGER

|

| SALES |

28,008

|

30,963

|

58,971

|

| CASH PROFITS |

3,401

|

1,888

|

5,278

|

| NET PROFITS |

2,142

|

1,269

|

3,411

|

| NET WORTH |

14,765

|

8,727

|

23,492

|

| ASSETS |

29,875

|

20,169

|

50,044

|

| Figures in Rs crore |

|

AN URGE TO MERGE

|

JULY 1975

RELIANCE TEXTILES

mergerd with MYNYLON*, a company manufacturing synthetic

blend yarns & fabrics, and polyester filament yarn.

MARCH 1992

RIL merges RELIANCE PETROCHEMICALS

into itself

SALES: Rs 3,005 crore

PAT: Rs 163 crore

MARKET CAP: Rs 9,783 crore

JUNE 1995

RIL merges RELIANCE POLYPROPYLENE &

RELIANCE POLYETHYLENE

into itself

SALES: Rs 8,085 crore

PAT: Rs 1,305 crore

MARKET CAP: Rs 5,566 crore

MARCH 2002

RIL merges RELIANCE PETROLEUM

into itself

SALES: Rs 58,000 crore

PAT: Rs 4,000 crore

MARKET CAP: Rs 49,000 crore |

Merging For Acquisition

It helps RIL too. Although RIL is a market leader

in petrochemicals, with marketshares of 50 to 80 per cent in polymers,

polyester, and fibre intermediates, the merger with RPL would help

insulate it against the volatility in naphtha prices, the feedstock

for its cracker. That will help, especially since in future, growth

and profitability in petrochemicals will be increasingly governed

by international price fluctuations of various end products. Also,

since RIL buys 25 per cent of RPL's output, there are big savings

in sales tax. Plus there are yet-to-be-calculated benefits like

the depreciation of the Rs 14,404-crore refinery at Jamnagar and

other indirect tax savings.

But the strongest benefit of the merger is

in how it could help in marketing of RPL's products. With the dismantling

of the administered price mechanism from April 1, 2002, Reliance

will have to market and distribute the refinery's output on its

own. That means building a network of retail outlets across the

country. Setting up a pan-Indian retail network could cost Rs 5,000

crore at the minimum. Besides, it is crucial for it to get a headstart

in marketing by acquiring the government's stake in either of the

two public sector oil majors-Bharat Petroleum Corp. Ltd (BPCL) or

Hindustan Petroleum Corp. Ltd (HPCL). The price tag for either of

these could be upwards of Rs 5,500 crore (for the government's stake

in one company, plus a 20 per cent open offer).

A merged RIL-RPL would probably find it easier

to raise that kind of money than an RPL alone. If RPL were to invest

Rs 5,000 crore, its debt:equity ratio in fiscal 2003 would have

been strained at over 1:1.5. For the record, Anil Ambani says the

company can now raise around Rs 11,000 crore (on a debt equity ratio

of 1:1). Plus, because RIL commands a better credit rating, the

terms at which fresh debt can be raised could be better. Says John

Band, CEO, Ask Raymond James: ''A better treasury management is

possible for capital investments.'' Reliance will have to be more

aggressive in its bidding for HPCL or BPCL, plainly because it lost

the chance to bag IBP. According to sources, Reliance's bid for

IBP was the fifth highest. This time, pitted against global oil

giants like Shell, Exxon-Mobil, BP, and Petronax, all of which have

refineries that are in the neighbourhood of India, Reliance will

have to do better.

Not A Slick Future

Although the Ambanis say the merger is good

for RIL's shareholders because the company gets assets worth Rs

21,000 crore by issuing shares worth Rs 11,000 crore, the merger

ratio of 1:11 hasn't excited the stockmarkets, which believe that

the stock price of RPL (pre-merger value: Rs 28) was undervalued.

Moreover, since the merger represents the folding of subsidiary

(RPL) into the parent company, all the benefits of integration in

the refining/chemicals chain were captured by the earlier parent-subsidiary

structure. To quote a DSP MerRILl Lynch report: ''We do not see

any visible near term synergies from the merger and would be cautious

of any sharp price rally on this news.'' Post-merger, the RIL stock

has moved from Rs 322.12 (March 1, 2002) to Rs 306.85 (March 8,

2002), reflecting the market's 'limited positive' reaction, at least

in the short term.

RPL's assets have been revalued at Rs 21,000

crore as against the value of Rs 14,830 crore as on March 2001.

Arun Kejriwal, an investment analyst, is critical of the structure

for merger: ''If 64 per cent of the shares held by RIL in RPL had

been extinguished and the remaining 36 per cent converted into RIL

shares at the current ratio of 1:11, they would have unlocked greater

value for RIL shareholders.'' Instead, 36 per cent of the RIL shareholding

in RPL, held through Reliance Industrial Investments and Holdings

(RIIHL) and RIL associate companies, will not be extinguished but

converted into 12 per cent equity stake in RIL held by RIIHL and

RIL associates. While the company says that these shares are for

sale in the future to create resources, it could weigh on RIL stock

performance.

While stock pundits keep watching its scrip,

the future for RIL isn't going to be a cakewalk. With lower tariffs

in the offing and a general softening of global petrochemical prices,

its inward-looking strategy of catering to the domestic market could

need revisiting. Globally, according to crisil, the profit margins

for global petrochemical producers have been under pressure over

the past two-three years, primarily on account of high and volatile

oil prices in 2000 and early 2001. Profitability has also been affected

by weak demand and prevailing overcapacity situation in many commodity

chemicals. True, after hitting lows in the third quarter of 2001-02,

polymer prices have picked up in the fourth quarter and are now

ruling at $480-500 (Rs 2,300-2,400) per tonne. Still, margins continue

to be under pressure. RIL will find the going tough if the government

is committed to reducing the import duty on polymers to 20 per cent

(Budget 2002 reduced it to 30 per cent from 35 per cent).

Then there are the new businesses that the

Ambanis have ventured into. Reliance Infocom, a 45 per cent subsidiary

of RIL, which is setting up nationwide broadband network to provide

fixed line, wireless, national long distance and international long

distance telephony as well as a range of data and value-added services,

is expected to require investments of nearly Rs 25,000 crore over

the next few years. Although the Ambanis say that the merger will

have no impact on Reliance Infocom, the market will be watching

to see whether Reliance will dilute its stake, perhaps through an

IPO, and go public with the company.

It will also wait to see what it does with

the 12 per cent of the RIL equity capital that is currently reposed

in a special purpose vehicle (trustee for RIHL and RIL associates).

This shareholding was an outcome of the fact that RIL held 64 per

cent in RPL and because under Indian laws, a company cannot hold

its own shares, therefore the ensuing 12 per cent will have to be

liquidated. Valued at Rs 5,400 crore, this stake may be monetised

in international markets, through sale to strategic and financial

investors. And the proceeds used to fuel the investments that are

on the cards.

Reliance has the ability to sometimes shock

and sometimes surprise. Less than a month back it was in the news

for the wrong reasons-with the Securities & Exchange Board of

India investigating whether its purchases of L&T stock (before

selling its stake to the A.V. Birla group) broke the law. Now, its

merger has taken Corporate India's breath away. What's going to

be next from India's second most valuable company with highest turnover,

the largest profits, and the most assets? Says a company wag, half-joking:

''Now that we have such an impressive balance sheet, perhaps we'll

go out and raise a billion dollars from the global markets.'' Maybe

he's not joking.

|